TuesdayMarch 31

The emergency room is at capacity right now. A lot of the anxiety comes from that fear that another wave is coming.

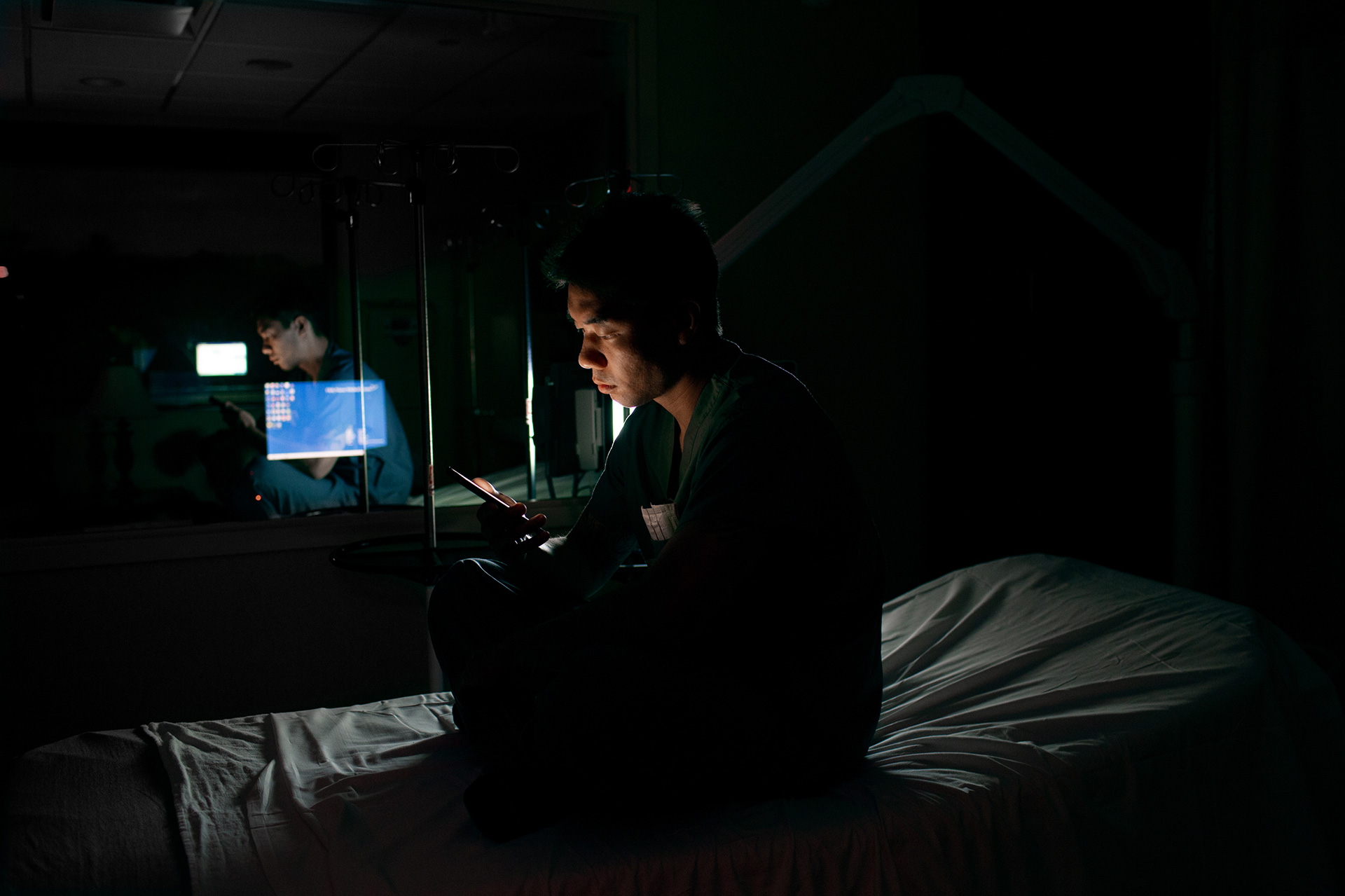

12:09 a.m. March 31. “I’m taking a break texting my wife, Stella. Right before I took that picture, I was having a conversation with her telling her I feel kind of guilty that I’m working so much.”

I spend most of my time on calls, showing up to people’s homes, trying to convince them to stay home if they’re not critical. There’s nothing else we can do for them at the hospital. At the hospital they run the risk of exposure to other things.

4:31 a.m.

A COVID-19 positive patient being prepared to be intubated by the anesthesiologist. The plastic tent is so the virus isn’t spread while transporting the patient between units.

4:57 a.m.

An ICU patient woke from a sedated state and needed to be re-intubated by the anesthesiologist. He’s wearing the most protection because of the viral load in the patient’s mouth and airway.

6:42 a.m.

Paramedic Brian Moriarty with the mask marks on his face, exhausted after a 12-hour shift.

1:36 p.m.

A volunteer ambulance driver looks back at the patient department while we’re treating someone on a call. Most of the volunteers are literally kids, like 16 to 25 years old. They’re unpaid.

1:53 p.m.

Paramedics Johnny Economou, center, and Joe Subrizi prepare to meet a 911 caller, double gloving his hands, responded to a call for a man complaining of vague symptoms. We encouraged him to remain home.

6:10 p.m.

John Cruz is one of the paramedics I personally work with. He got sick with the virus and came to the ER with bilateral pneumonia. I thought he was going to die. He’s getting better.

7:52 p.m.

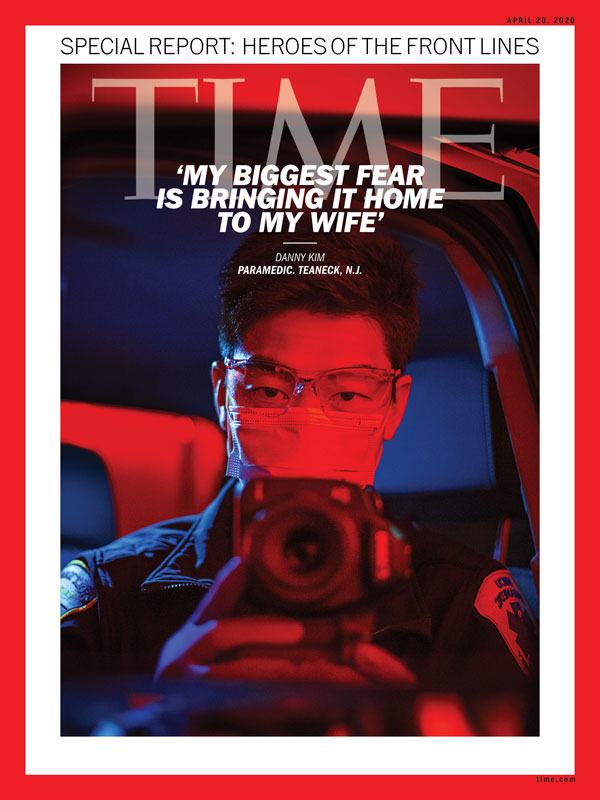

That’s John Joyce and me sitting in the truck. We were told by our supervisors to wear a mask all the time. I don’t think everybody does, but I roll my windows down.

WednesdayApril 1

Everyone at work is like, ‘We're going to get it sooner or later.’ I worry that I'm already exposed. Maybe I'm asymptomatic. They're not testing asymptomatic patients. The only way I could find out is my wife. She's kind of my indicator. Like if she starts getting sick, it's probably most likely from me because she's home all day, every day.

6:46 a.m.

Our supervisor James Fox said he loses sleep because he doesn’t want any of us to get sick. Every morning at 5:30 he disinfects our trucks, and today he disinfected our personal vehicles as well.

7:17 a.m.

This is the routine. Take off my uniform before I go inside the house. No hugs, no kisses. Just straight to the shower.

5:38 p.m.

In a nursing home, a patient fell and cut her head. A mobile intensive care nurse is applying an oxygen mask specifically for COVID-19, with white HEPA-filters on the mask.

5:39 p.m.

She cut her head. She was unconscious. We’re just putting the mask on her while the other person is checking her head for any other injuries.

8:50 p.m.

Christine Lowe has been an EMT for Holy Name for six and a half years. Here she’s turned speak to one of her coworkers between calls.

ThursdayApril 2

Two of my coworkers, they were admitted to the hospital because they tested positive for the virus, and they're becoming more sick. So a lot of the questions that I was asking myself, I was asking my coworkers on camera. And I really felt compelled to do this because as more and more people get sick in my immediate circle — my coworkers, I really want our voices to be heard.

We have a total of three coworkers who tested positive and they're older. I know both of them. They're diabetics. One has asthma. They have preexisting medical conditions, and I'm really concerned for them. I'm f-cking scared that they're going to get intubated and never wake up out of it.

FridayApril 3

Working as paramedics inside the hospital is unique to Holy Name. They are giving us responsibilities that we have never done before, but it is within our scope of practice too. The state also issued a waiver for allowing the paramedics to work inside.

3:54 p.m. “This gentleman, he was 32 years old. It looked like he was more having a panic attack, anxiety. We evaluated him, did an EKG, checked everything out, his vitals were stable and he stayed at home.”

When I walked in, I'm like this looks like a TV set. TV studio, because the exterior of the structures, it's like you could see the exposed 2 by 4s and plywood, with all these wires running through it. And then on the inside, it's like where all the action is taking place. I was blown away by the design, and just how they came up with the idea. And how fast they built it. It was amazing.

(In the following gallery, two photographs are obscured in a small portion, to preserve patient confidentiality.)

10:24 p.m.

A patient coming up from the ER to what we call the Shell ICU under the plastic canopy used to transport COVID-19 patients.

Pumps and medications must be adjusted frequently, and PPE changed after every visit to a patient’s room.

10:40 p.m.

Moving the gear into the hall, between the new units, reduced PPE use from 20 or 30 per shift to five or six.

10:41 p.m.

Nurses and patient care technicians make their rounds maintaining ventilators, IV medication pumps, emptying and collecting from urinary catheter bags and change bedding as needed.

4:00 a.m.

Staff transport a body out of the intensive care unit.

SaturdayApril 4

I can’t wait for this quarantine to be over. The most f-cked up thing about this virus: People are dying alone. One of my coworkers brought a lady to the hospital who died shortly after. She had no name, no ID, nothing to identify her. She died with no name around strangers.

The way people are experiencing this is very polarized as well, because you have the general population who's either A) they're not sick, or B) they're pretty mild and they're quarantined at home and they're not experiencing the seriousness of the virus inside the hospital. From my point of view, as the week progressed, I felt like I was seeing more and more sick people, especially as the new ICU opened.

5:32 p.m.

EMT Paige Schmelz helps Andres Faciolince don PPE before taking home a woman who was discharged from the hospital.

6:37 p.m.

The woman had been admitted with a confirmed case of COVID-19. When she returned home her family was waiting on the steps, her daughter in mask and gloves.

6:39 p.m.

The ambulance crew helped her children, and basically took her up the stairs and put her in bed.

SundayApril 5

Cases seem to be escalating. I'm working a lot more inside the hospital as well. So from my point of view the volume of sick patients seemed a lot higher as the week progressed.

The hospital is planning to open three more isolation structures similar to the Shell ICU. I think they're still working out the details of how they're going to staff those and also be prepared for a surge in patients.

6:36 p.m.

The outside of the ER is known as “tent city.” It’s where people who suspect they may have COVID-19 can come for screening.

6:43 p.m.

The testers take a break at the end of the day.

TuesdayApril 7

When I walked in there was a thirty-nine year old man laying in bed and he showed obvious signs of death, like he had some blood pooling in his hands. And what was really different about pronouncing people during this pandemic is, I’m unable to create a space where I’m, like, I’m really sorry and try to be compassionate to the whole situation. Because I’m alone in this room, wearing all this plastic PPE gear, an N95 mask, a surgical mask and then goggles and then another plastic shield on top of everything and then a full body apron and two pairs of gloves and I’m just like this completely sealed figure saying like hey, your father’s dead.

I’m really tired. Really tired, man. Part of me feels like this is an amazing point in two of my careers meeting during this pandemic. I really hope the work that I did, both as a paramedic and as a photographer is going to give something back. And I also hope that it’s my last photo assignment too, to tell you the truth.

ThursdayApril 16

Good news! Today the hospital discharged the first extubated patient.

The hospital said, “68-year-old Shuomimg Liu was hospitalized March 17, intubated March 19, extubated April 3 and went home today.”

This moment was an antidote to all the sickness and death we saw in the past few weeks. The work, the risks, the fatigue, the long hours were worth it to see this one patient be discharged.

Editor’s note: This post has been updated to include the final chapter.

If you would like to support front line organizations helping in the fight against COVID-19, including Holy Name Medical Center, please visit TIME.com/giving