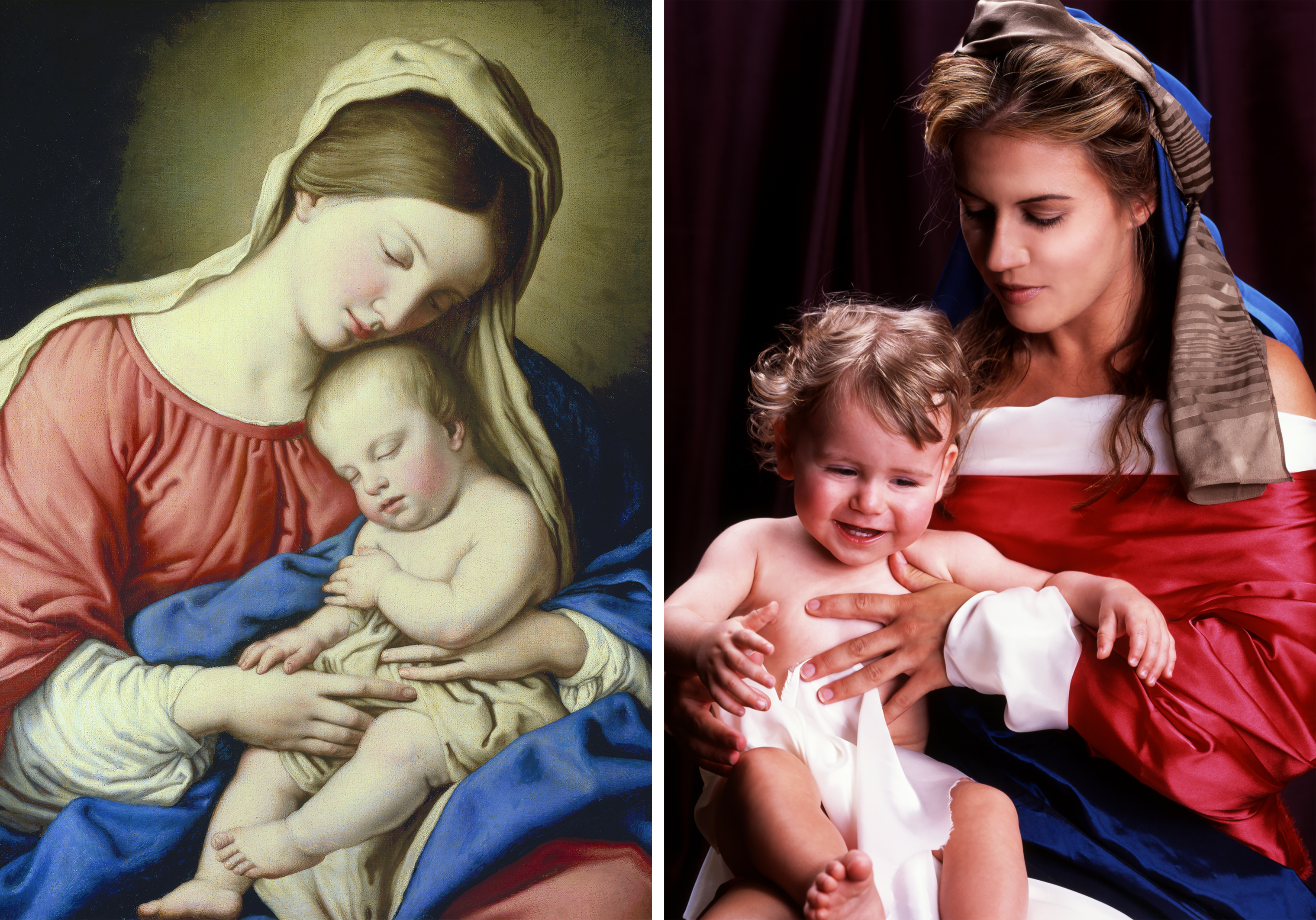

Sixteen years ago, artist Nika Nesgoda made a series of Cibachrome photographs, in which — taking a page from Caravaggio — she recreated iconic paintings of the Virgin Mary using adult film actors as models. There was no way she could have predicted that she’d wake up one day to find that one of her former models, Stormy Daniels, was at the center of a political, cultural, legal maelstrom that could alter the course of American presidential history, or at least the cold open of Saturday Night Live.

But then again, who could have predicted any of the events of the last two years? Or two days. Or two hours. So let’s try to remember 2002, when we were still a nation capable of shock. Back then, Nesgoda’s printer refused to make prints of her Virgin Mary photographs. Realizing that he must have recognized her models from their day jobs, Nesgoda was embarrassed before thinking, Hey, wait a minute. This man is judging me?

We can maybe forgive the printer’s prudishness. This was long before a site called Pornhub had 28.5 billion visits a year, and before we talked about Game of Thrones sex scenes over dinner, and certainly before we had a President admitting on Twitter to paying hush money to a porn star just before commemorating the National Day of Prayer in the Rose Garden (where he said, rather hopefully: “America is a nation of believers, right?”).

Given all that, there’s some irony in the fact that Nesgoda’s project was inspired in part by a 17th-century scandal involving a sex worker. Nesgoda became fascinated by the backstory of one of Caravaggio’s most famous paintings, The Death of the Virgin. The work caused an uproar in 1606 because the Italian master reportedly used his mistress, a prostitute, as a model. The Roman parish for which the painting had been commissioned rejected it, and for decades it was rarely shown in public.

Raised a Catholic, Nesgoda chose the Virgin Mary masterpieces she wanted to recreate in larger-than-life prints after obsessively researching their history — the painters’ lives, the models they used, the Christian iconography. She set up her shoot in an old penthouse on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, adjacent to the cemetery where Marilyn Monroe is interred. Using porn film actors to portray Mary seemed fitting to her for a lot of reasons. “The models in my pictures are both marginalized and glorified,” she explains. “Like the Virgin, they are untouchable and misunderstood.”

The actors were all “polite, punctual and funny,” says Nesgoda. One brought her baby, and Nesgoda was able to make a Madonna and child portrait. Most of all, she remembers them as enviably comfortable in their own skin: “These women didn’t seem to have hang-ups about their flaws, like so many of us do. Some had full Rubenesque thighs, dimples and all and they didn’t give a damn what anyone thought of them. I admired that.”

And what about Stormy Daniels? A makeup artist recommended her for the project and Nesgoda remembers him saying, “You’ve got to put this woman in one of your pictures — she’s magical on film.” When Stormy, whose real name is Stephanie Clifford, arrived at the studio, she seemed quiet and studious — just taking it all in.

Nesgoda thought Stormy had the elusive quality necessary to recreate a famous Annunciation scene from a 1333 Italian altar painting by Simone Martini and Lippo Memmi. In it, the Virgin Mary looks “intelligent and as though she’s seen some things,” says Nesgoda. “Stormy’s eyes carry a lot of depth, which was perfect for this image. I was struck by the timelessness of her beauty. She really looked like she could have stepped out of the 14th century.”

Stormy Daniels also looks right at home in the 21st century. She is both witness to and catalyst of much of the spectacle unfurling around Donald Trump. As the reputations of almost everyone in the President’s orbit implode in real time, she stands slightly apart from the verbal brawls between lawyers and pundits on cable TV. But the object of our speculation and obsession is more the idea of Stormy and what she does for a living, than the reality of her as an individual — not unlike the women in the masterpieces that inspired Nesgoda.

You get the sense that when the history of this manic period is written and illustrated, Stormy Daniels may well fare better than many in the unlikely cast of characters now center stage. There is President Trump, who denies Daniels’ allegation that the two had sex in 2006, during his marriage to Melania Trump, and who Daniels is suing for defamation. And there’s Trump’s newest personal lawyer, former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, who said on May 2 that Trump had funneled a $130,000 payment to Daniels just before the 2016 presidential election, in exchange for her silence. (Trump had denied this and on May 4 said Giuliani got his facts wrong.) Lastly, there’s Michael Cohen, another Trump lawyer, who negotiated the non-disclosure agreement with Daniels, paid her and is now being investigated by the FBI. It is quite a tableau — one destined for our kids’ textbooks whenever we find out how this all ends.

That rendering of Caravaggio’s beautiful mistress posed as the dying Virgin Mary outlived the church controversy it precipitated. After being closeted away for decades, the painting ended up in the collection of France’s Louis XIV, the Sun King, who believed he was infallible and was infamous for declaring ‘‘l’État, c’est moi”: I am the state.

It’s hard not to wonder whether, in hindsight, we’ll remember this era as being as dramatic as it feels in this moment. Who knows, a few generations from now, a portrait of Donald Trump in the National Gallery might look positively staid in that long line of American presidents. It all depends on what comes next.

You can see Caravaggio’s formerly scandalous masterpiece in the Louvre. Find more of Nika Nesgoda’s work here.

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now, You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time