No night is ordinary when you hunt pythons for a living. But even by snake hunting standards, the July night when TIME accompanied Donna Kalil in the Florida Everglades was a night to remember.

The real estate professional turned “python elimination specialist” was out with her daughter and fellow python chaser Kevin Pavlidis, searching for the invasive snake when she hit the mother lode: a 15-and-a-half foot python looking for prey of its own. Before long, the giant snake wrapped around her leg and began to pulse — the subtle yet effective way it kills its prey. “It was like a vise,” Kalil recalls calmly.

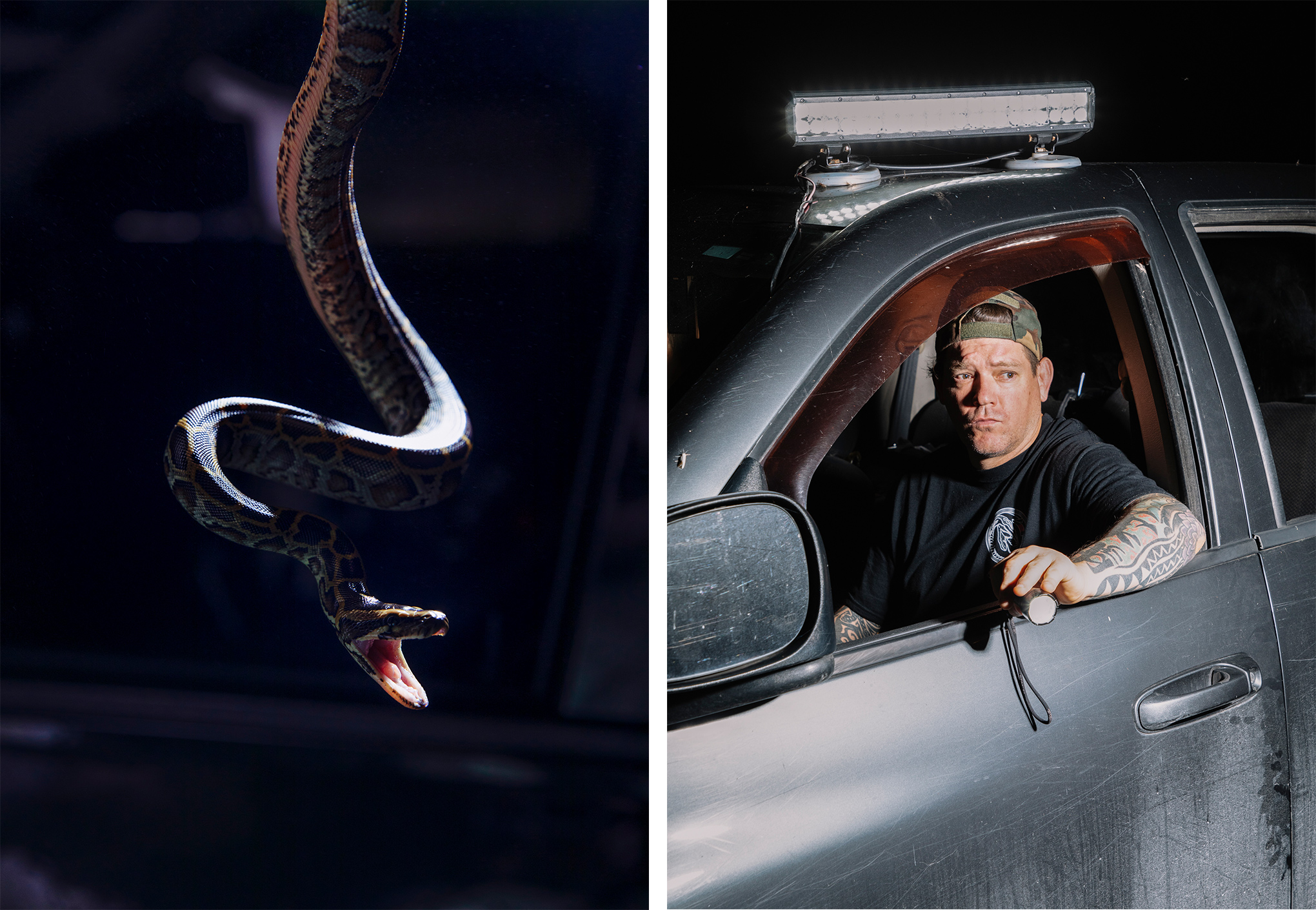

This wasn’t the first time a python latched onto her, but for the first time she struggled to pull it off. Urgently, she grabbed the head and looked for help as Pavlidis and her daughter jumped in and helped wrestle the snake off her leg. Eventually, Kalil managed to escape the snake’s clutch and get it under control.

Kalil is one of roughly 30 python elimination specialists working for the South Florida Water Management District who spend their nights hunting South Florida for what may be the country’s most infamous invasive species. Pythons, native to Southeast Asia, have been imported to the U.S. as pets for decades, with imports growing in the 1990s. (The snakes are not venomous, but are constrictors who kill prey by squeezing it to death.) Many of the nearly 100,000 pythons the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services say were imported between 1996 and 2006 were likely released by their owners when their enormous size made them unwieldy. It was around that time when scientists began to notice them at concerning numbers in the wild.

Today, scientists say tens of thousands of pythons roam the Florida Everglades and nearby areas including Big Cypress National Preserve. It’s hard to know the precise number spread across more than a million acres of Florida wetlands, but it’s clear that there’s cause for alarm.

The local ecosystem has suffered in the grip of the snake. Raccoon populations declined around 99% between 1997 and 2012; bobcat populations declined more than 87%, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. These population losses ripple across the local food chain, and because the natural area plays a critical role supporting the local economy, the spread of the python also affects humans, putting the livelihood of locals at risk.

Kalil — along with the others captured by photographer Peter Fisher over a week in Florida — is working to stop that. The self-described “naturalist and environmentalist” says she cried the first time she had to put a snake to down. “It really, really bothered me for days,” she says. “They’re absolutely astounding creatures; they just don’t belong here.”

But that hasn’t stopped her: She’s caught more than 200 snakes in the less than three years she’s hunted pythons. As of late October, the South Florida Water Management District had eliminated nearly 2,700 pythons in the same timeframe.

The snake may be the best-known invasive species currently on the loose in the U.S., but it’s just one of thousands. As globalization has drawn the world’s economies closer together, the world’s wildlife has also intermingled. The results haven’t been pretty. Feral hogs originally from Europe run amok in the fields of Texas, disrupting local farmers. Asian carp have taken over in the Great Lakes, beating out other species for limited food and lowering water quality. Meanwhile, goats on San Clemente Island off of California threatened to drive native plants to extinction.

Scientists have discussed a range of new ways to try to stop these species — from gene editing invasive rodents to new screening regulations for plant and animal life entering the country. But, in the meantime, many communities will continue fighting just like Kalil: one by one.

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time