Pat Martin has spent the past two years photographing his family, at age 26, creating his only photo album. Children grin for the camera. Siblings sit together. Grandparents hold each other. Each shot glows with the golden heat of Los Angeles, where they live. There is a simplicity and peacefulness in the frames that wasn’t always present earlier in Martin’s life.

In 2016, Martin had no family photos at all. The truth sunk in one day as he and his brother Drew rifled through boxes that had been locked in a storage container and held relics of their past life. It was six years after Martin and his mother had been evicted from their Los Angeles apartment, he remembers. And they found that mold had spent the intervening time creeping through the pages of their albums. Pictures with relatives, grade-school portraits, baseball-league photos — the dark spores plagued and destroyed years of images. Just a half-full album of baby photos survived.

This wasn’t far from the status quo for Martin, who never had the kind of childhood that made for smiley family portraits or colorful candids. He explains that his parents met through their drug addictions, and his dad left when he was three years old. Martin’s brother, around 16 years his elder, took on many parenting responsibilities. By high school, his mother could no longer pay rent, and the household splintered apart, with Pat taking up residence at his best friend’s family home in the cupboard under the stairs. Seeing that family’s albums, he tells TIME, reminded him of what he never knew.

“Typically when I look at other people’s family albums, it just triggers my childhood and what I wish I could have had,” Martin says.

By the time Martin and Drew went through the storage container, Martin’s family showed signs of recovery. Martin’s mother, Gail, had been in and out of rehab for drug abuse, which led to a period of homelessness. Then when Drew started a family, becoming a grandmother seemed to give Gail a renewed sense of purpose, Martin says; she stayed clean and lived on her own.

Martin’s family was growing and changing for the better, but he says he still held his relatives at arm’s length. He felt ashamed of his shame. He recalls that it took his mother having a major health crisis around that time to make him realize he wouldn’t have his family forever.

So he started taking photographs.

“Creating this new picture of us and documenting this present moment in time has helped me control a part of my own dynamic with my family,” Martin says. “I recognized that I could have some control over these things.”

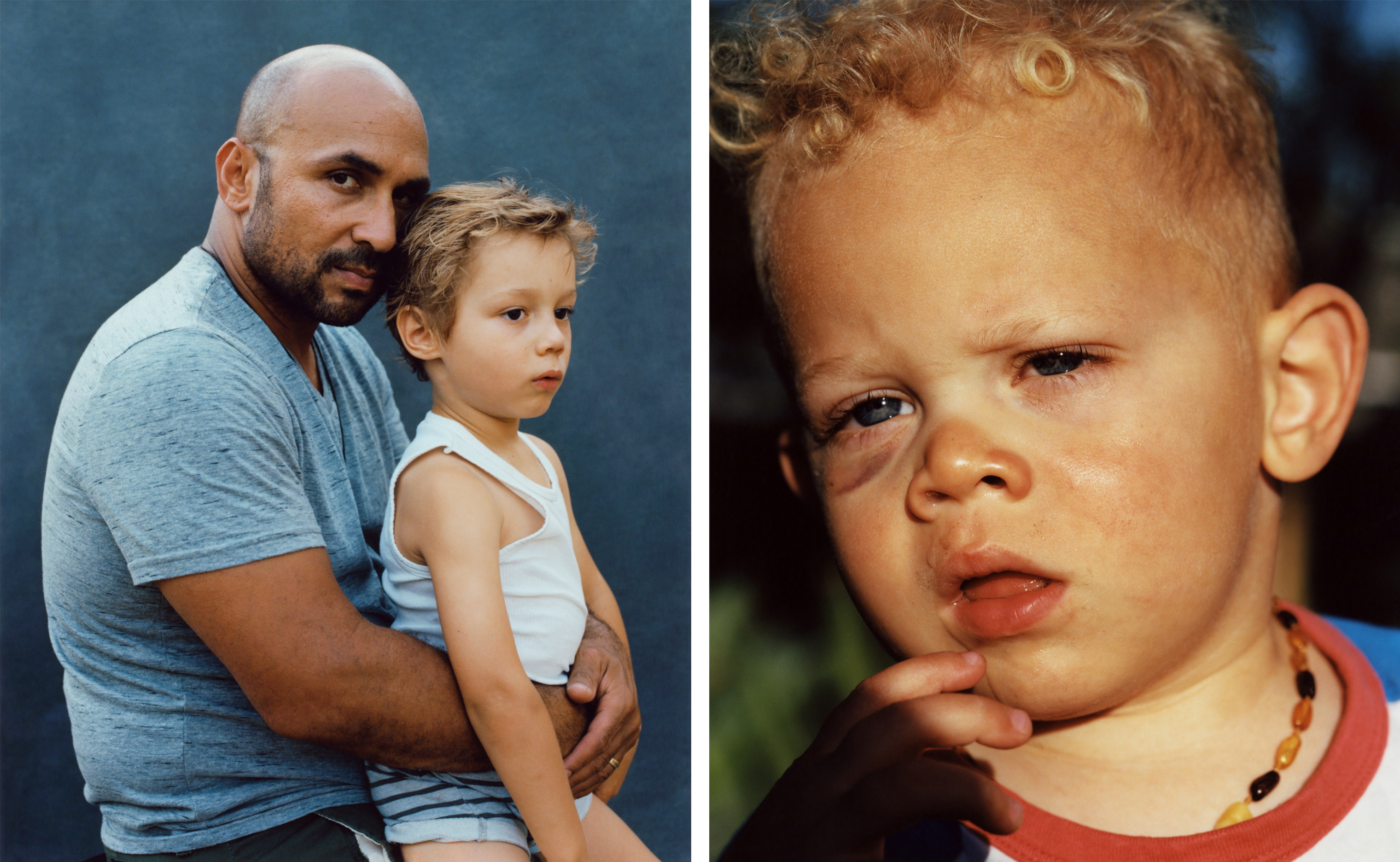

His new family album shows off his new family members. There are his nephews, ages three and four, and his six-week-old niece. Drew has changed, too — from a father-figure into a real father. Martin also loves photographing his three grandparents, who are actually his girlfriend’s grandparents and treat him like part of their family.

He takes portrait after portrait of his mother. He wants her to see her images and feel beautiful, in a way she usually doesn’t, Martin explains. And he also turns to those pictures of her to recalibrate his own emotions towards his family.

“When I would feel moments of stress with my mom, for example, I can look at these images and they show me a different side of things,” Pat says. “I’m creating a beautiful perspective of my mom because I haven’t had that for so much of my life.”

There is a floral motif that runs through many of the photos. Martin says it wasn’t intentional — that his lens always seems to find flowers in bouquets, on fabrics or growing outside. They’re delicate, and they have such short lives, he adds, likening them to how fragile his family feels at times.

“Age, life — flowers to me represent the essence of that: How quickly they grow into something beautiful and completely fall apart,” Martin says.

The consistent warmth of the album wasn’t a conscious decision either, but Pat found that he’s drawn to those shots as he edits. Martin describes the work as “therapeutic,” and he says he’s using the project to simultaneously re-document his family and work through his complex relationship with them. “My general feeling about my family is cold,” he says. “I don’t like that.” So his images have the opposite color palette. He hopes his memories will, too.

The series is marked by shadows his family members cast or that are cast onto them, sometimes by Martin’s own body when the sun is behind him. He can’t help but notice those shadows, especially on sunny days. He sees the symbolism. “I’ve been tapping more into the shadow of my family,” Martin says. “This helps that feeling of love come back.” He often looks over his own photos to remind himself of that joy, so he can see his family more completely, with both its imperfection and its sweetness.

Martin doesn’t know how people will take the photos, given his family background. But many may recognize glimmers of their own experience. The most recent data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicates over 7.5 million Americans age 12 or older suffered from drug abuse or dependence in 2017. When also considering alcohol addiction, the number of Americans with substance use disorders rose to roughly 22 million — or almost one in twelve people — during last year alone.

As many families across the country assemble for the holidays, many will struggle with, confront and heal divisions at least in part caused by addiction. Through his work, Martin has seen how his family’s story extends far beyond that aspect — and that it continues to evolve.

“I hope,” Martin says, “that anyone who can relate to the details of my family story and sees these pictures won’t feel as isolated.”

Julia Zorthian is a reporter for TIME. Follow her on Twitter at @jzorth.

Pat Martin is a photographer. Follow him on Instagram at @patmartin__.

Dilys Ng, who edited this photo essay, is a photo editor at TIME. Follow her on Instagram at @dilysng.

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now, You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time