By Katy Steinmetz

On a playground in San Francisco, 4-year-old Astral Defiance Hayes takes a stick and writes his name in the sand. His twin brother Defy Aster Hayes whizzes around their father.

When the boys pause for snack time, Lucas, 33, a tattooed stay-at-home dad, peels each of them a banana. One of them balks. “You don’t want it? But I opened it for you.” Lucas caves and pivots to some raw walnut pieces.

Astral and Defy have been vegan since they were in the womb. Lucas cloth-diapered them, and now he’s home-schooling them while his wife Kenya, 36, supports the family with her PR job. The Hayeses started documenting their adventures as parents, Instagram photo by Instagram photo, on a blog about vegan pregnancy that has become a blog about vegan childhood. The family even has its own semi-satirical tagline: “Committed to raising kids sustainably and humanely since 2009.”

“You guys can go wherever you want,” Lucas tells the boys as they tentatively explore the park. “Walk, and we’ll follow you.”

Until now, members of the millennial generation—those 20- and 30-somethings born from the late ’70s to the late ’90s—have mostly been busy following themselves. Helicopter-parented, trophy-saturated and abundantly friended, they’ve been hailed by loved ones as “special snowflakes” and cast as the self-centered children of the cosseting boomers who raised them. Now millennials have a new challenge that has shifted their focus: raising kids of their own.

Millennial parents number more than 22 million in the U.S., with about 9,000 babies born to them each day. This growing cohort of parents is digitally native, ethnically diverse, late-marrying and less bound by traditional gender roles than any generation before it. Millennials, many of whom entered the job market during one of the worst economic downturns in U.S. history, have helped shape a culture where everyone is expected to be on all the time—for their bosses, co-workers, family and friends. With a smartphone and a social network always at hand, they’re charting a course through parenthood that opens moms and dads to more public criticism—as well as affirmation—than anything previous generations have ever experienced.

At the same time, these young adults, having been raised to count individuality and self-expression as the highest values, are attempting to run their families as mini-democracies, seeking consensus from spouses, kids and extended friend circles on even the smallest decisions. They’re backing away from the overscheduled days of their youth, preferring a more responsive, less directorial approach to activities. And they’re teaching their kids to be themselves and try new things—often unwittingly conditioning their tiny progeny to see experiences as things to be documented and shared with the world.

As parents, millennials are still marked by their optimism. They still have faith in progress, equality and Google. And they continue to build vast archives of selfies. Now the rising question for this generation is, How will their beliefs, habits and preoccupations shape the lives of their children?

Ali DePlatchett, a 31-year-old research administrator and single mom in Cleveland, calls it “mom-petition.” Social media, she says, is the worst. “I’m like, ugh, there’s a 7-month-old walking on Facebook. What are you doing, Liam?”

She’s joking about worrying that her son is behind. Mostly. Like other millennial parents, DePlatchett endures the constant temptation to compare her family with others. Nearly 90% of millennials are social-media users, compared with 76% of Gen X-ers and 59% of baby boomers, according to market-research firm eMarketer. The result is that many of them are posting an impossibly pristine, accomplished version of their family lives on the web.

In scores of interviews for this article, just the mention of social media elicited groans and sighs from young parents who are barraged by hand-made birthday invitations and color-coded clothespin chore charts on Pinterest. They debate whether Facebook or Instagram is “the hardest,” whether it’s the images of the home-cooked organic feast or the just-cleaned house. It helps only a little to know that people are being highly selective about what they share. “Someone will put out there, ‘Oh, I just braided my child’s hair.’ But you just yelled at them like 50 times to sit down,” says 30-year-old B. Marcell Williams, a mother of four living in St. Louis.

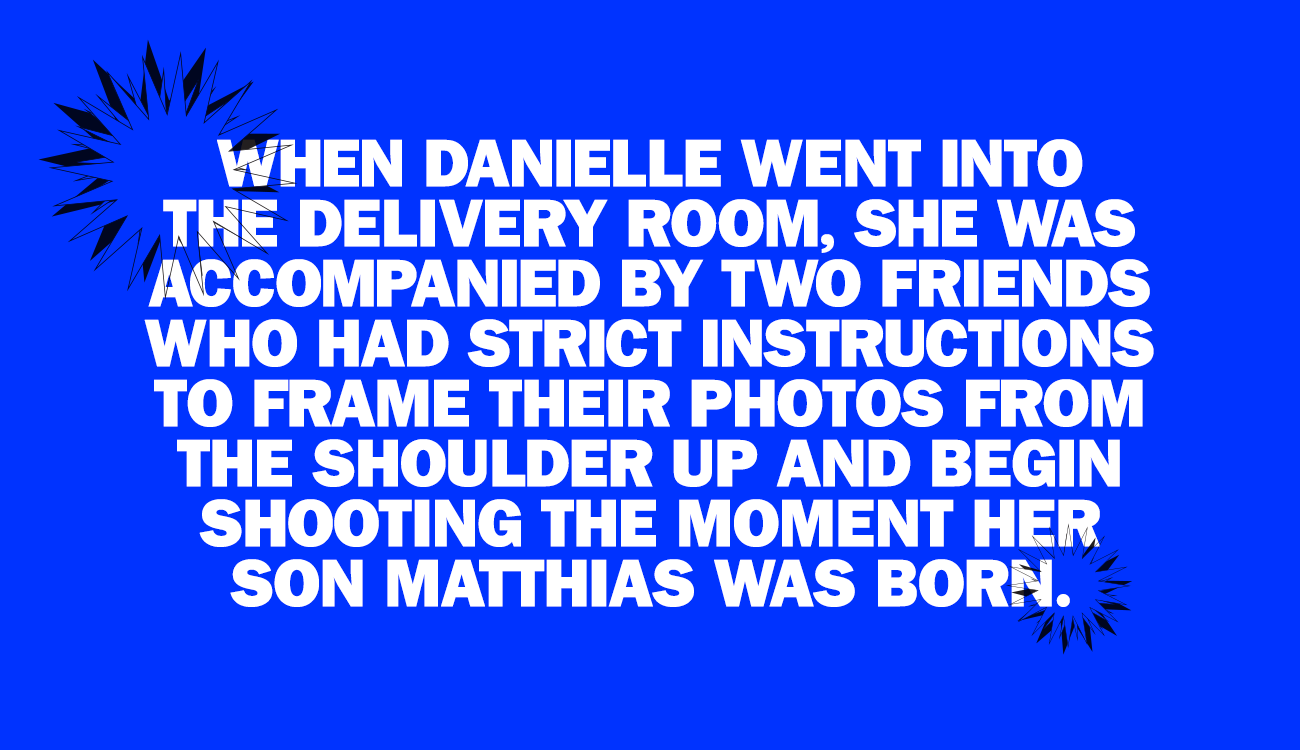

Social-media platforms have become places where it’s acceptable to brag, as parents have done since they had kids to brag about. But whereas previous generations had five minutes to whip out their wallets at the water cooler, millennials have a platform that operates 24/7, with HD video—one that they’re not shy about using. When Danielle Campoamor, a 28-year-old freelance writer in Seattle, went into the delivery room last year, she was accompanied by two friends who had strict instructions to frame their photos from the shoulders up and begin shooting the moment her son Matthias was born.

“He was online moments after he took his first breath. Who doesn’t want to hear that their kid’s cute?” she says. “And especially as a parent—when so much of it is self-doubt and a lot of guilt about whether the decisions you made are right—we want to hear that we’re doing a good job.”

The pressure among millennials to be great parents is fierce. In February, parenting site BabyCenter released its annual report on modern moms. It surveyed 2,700 U.S. mothers ages 18 to 44 and found that nearly 80% of millennial moms said it’s important to be “the perfect mom,” compared with about 70% of moms in Generation X; 64% of moms across age groups said they believe parenting is more competitive today than it used to be.

And for millennials, that competition is starting earlier and earlier. In a TIME poll conducted in partnership with SurveyMonkey, 46% of millennial parents said they posted a picture of their youngest child either in the womb or before the baby was 1 day old, compared with 10% of Generation X parents. In their first blog post about vegan pregnancy, the Hayeses posted pictures of Kenya’s positive -pregnancy tests.

There are costs to putting every parenting choice on display in today’s digital public square. Every post or tweet invites opinions on one’s choices from the typical millennial’s network of 500 Facebook friends (at least half of whom are likely to be loose acquaintances). And the pseudo anonymity that people feel behind a keyboard can lead them to make comments online that they’d never make to another parent’s face. Many millennials say infighting over topics like breast-feeding and vaccines has driven them from online groups. Jodi Meyer, a 35-year-old mom in Oregon City, Ore., recently transitioned from working to staying at home full time. “Half of my friends on Facebook are like, ‘You need to work, you need to contribute to the family,’” she says. “It’s out there for stay-at-home moms. It’s out there for breast–feeding. Cloth diapering. It’s just like fight, fight, fight, fight, fight.”

And yet for all the bickering and sizing up, the vast majority of millennial parents remain online. Some cite the simple efficiency of posting on Facebook over emailing baby photos. Stay-at-home dads say they would have felt isolated if they couldn’t have found other guys online who were also full-time caregivers looking for solidarity and playdates. And every post that invites judgment is also an opportunity to receive support from relatives and friends no matter where they are.

Sarita Schoenebeck, an assistant professor at the University of Michigan, interviewed new mothers about their use of Facebook. She found that each Like they got when they posted a baby picture, no matter how well they knew the person it came from, was a form of much-needed support during the early, challenging days of being a parent. “Most parents play out, consciously or subconsciously, this cost–benefit analysis,” Schoenebeck says. “And the benefits of being on social media, for most people, outweigh these public parenting costs, this Pandora’s box of judgment and criticism and social comparison that is inherent to parenting today.”

Also inherent to parenting today: information overload. Whether they have questions about screen time, co-sleeping, all-natural remedies for -diaper rash or any other issue, millennials are twice as likely as boomers to say they look to Google most often for instruction—and half as likely to say they look to books. While parents of all ages are most likely to turn to their own parents for advice, millennials cast their net to Facebook, Twitter, blogs and apps.

This generation has no Dr. Spock. They have a zillion competing Facebook friends and Internet “experts”—none authoritative and many contradicting one another. In TIME’s survey, 58% of millennial parents found the information available to them somewhat, very or extremely overwhelming—compared with 46% of X-ers and 43% of boomers.

Trying to weed through everyone’s opinions and decide which is the most reputable can turn into an enormous time suck. Alyssa Westring, 35, is raising her 6-year-old and 3-year-old while teaching business students at DePaul University in Chicago about management and work-life balance. Yet that expertise didn’t shield her from the black hole that the Internet can turn into for today’s young parents. She recalls a day when her daughter started complaining that her ear hurt. The family had just moved, and Westring wanted to find a new pediatrician.

“How would I find a new pediatrician 20 years ago? I probably would have asked one or two people,” she says. “Now I can read reviews of all the doctors online and look at where they went to medical school. I emailed a listserv. And this fairly simple question became a several-hour ordeal.” In the end, she was so frustrated that she ended up just sticking with her original pediatrician—45 minutes away on the other side of Chicago—and feeling guilty about spending so much time researching a personal issue while she was at work.

DePlatchett says she “fell into” crowdsourcing advice from the web in the beginning. “When you’re on maternity leave and you have a new kid and you have no idea what you’re doing, the natural reaction is to look on the Internet,” she says. “Like ‘My newborn won’t stop screaming, what should I do?’ You Google it, and then you end up on a mom group on Facebook. Some of these women are just crazy. Everyone has their way to do things, and it’s right. They decided that it’s right.”

While still on maternity leave in Oakland, Calif., Rose Tandeta, a 32-year-old child life specialist, remembers her own personal rabbit hole. “I spent a lot of time on Google searching ‘My 6-week-old won’t sleep … My 8-week-old won’t sleep.’ You have all of that available to you, and sometimes that’s detrimental. I feel like I have to let her cry it out. Or I have to do this method. Or I have to read this book first,” she says. “My parents, they had their parents to say, ‘This is how we did it. This is how you should do it.’”

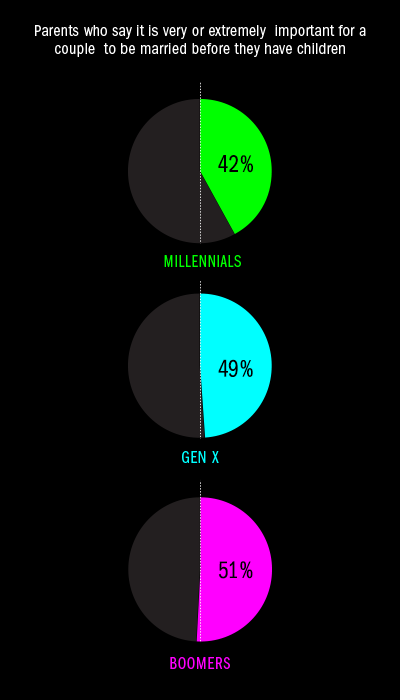

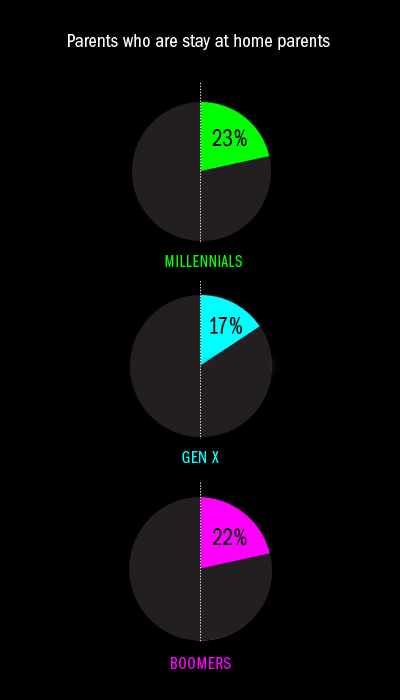

Many millennials, though, aren’t doing things the way their parents did. For one thing, they are becoming parents later. The average age of a first-time mother is at a historic high of 26, up from 21 in 1970. Millennial parents also put less value on marriages, many choosing to cohabit with their partners instead. Another big shift is from the helicopter parenting that achievement–obsessed parents inflicted on their millennial children to what might be called “drone -parenting”—the parents still hover, but they’re following and responding to their kids more than directing and scheduling them.

Data scientist and sociologist Lauren Beresford, a millennial who works for a company called Sproutling that makes wearables for babies, says that while some in her generation are still intensive parents, a huge number want the opposite experience for their children. “It’s not like: tennis lesson, music lesson, art lesson,” she says. “It’s a backlash.”

Allison Romero, 32, says her mother helicoptered her furiously during her childhood in Memphis and other towns—until her parents divorced when she was a teenager. “She had to have control over everything,” Romero says. “She never let us attend things on our own, whether it be a church service or a sporting event or anything. I felt like I always had to be on. I had to play the role of the perfect daughter.” Though Romero believes her mother had good intentions—“I think she felt that if she didn’t do what was best for us, she was failing us”—she also says that this exhausting presence drained her enjoyment out of the activities she was being ushered to and from.

Romero, now a stay-at-home mom to four kids, is taking a much more relaxed and responsive approach to raising her own children. “I wanted to be more of their friend than their mom and give them the room to express themselves and be little people,” she says. “I never felt like I got that opportunity.” Instead of hyperdirecting their kids, many researchers believe, there’s a focus among today’s millennial parents on a democratic approach to family -management—constantly canvassing their children for their opinions.

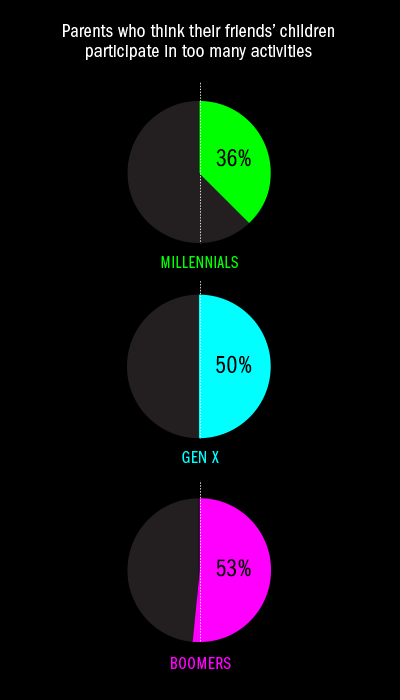

Jeff Fromm, a marketer who specializes in millennial attitudes, has studied this generational response. A 2013 report by his firm, FutureCast, found that 61% of millennial parents believe that “kids need more unstructured playtime.” And they see themselves as living up to this ideal as parents, with only 21% saying their kids are “overscheduled.” Fromm thinks this generation’s reputation for being entitled is actually a misunderstanding of its insistence on fairness. “The command-and-control model is not there,” he says. “Millennials are just at their core believers in democracy. It’s not uncommon for parents to poll the jury on what we are going to do this weekend.”

Running a family democracy, of course, is a lot of work. Kyle Eichenberger, a father of two in Oak Park, Ill., says he lets his kids choose what to eat and how to dress—and admits that it can be tiring. “Lately it’s been driving us nuts. We’ve been getting a lot of ‘Can I have a special treat? Can I have a cookie?’” he says. The kids don’t always get the cookie, but the parents also never make them finish what’s on their plates. “I’ve heard older people make disparaging comments about my generation, that parents are so lenient,” Eichenberger says. “It’s not that we don’t have rules and guidelines. We recognize that what works for my family might not be what works for your family.”

Sari Powazek, who’s been running a toy store in Scottsdale, Ariz., for nearly 40 years, has observed this back-and-forth. She says the parents she sees in the store’s play area today are more hands-on than previous generations of parents—and they are also looking to their children for direction. “They question themselves, they question the child. ‘Are you sure? Are you sure? Is this what you want?’” she says.

Open-minded. empathetic. questioning. These are qualities millennial parents list when asked what they want their kids to be like when they become adults. And these millennial parents may be achieving their desired result. Powazek says that while the parents she sees at her store are constantly questioning, the kids seem more confident and more verbal. They’re used to talking and wanting to be heard.

JoAnn Jones-Jackson, 58, is a first-grade teacher at Mather Elementary School in Dorchester, Mass., and she’s been teaching 5-to-10-year-olds over the past 29 years. She has even taught the children of her previous students. “You have to do more to hold their attention,” she says of today’s kids. But, she adds, they are also more engaged with their learning and flexible in how they interact with the world.

Jones-Jackson gives the example of how she teaches spelling. In the old days, she just put a single list on the board, and everyone was tested on that list. Now she uses a spelling program that is much more individualized. The kids help come up with the spelling words; they each get their own “special list,” and they choose to do different exercises. “I couldn’t even imagine doing something like that with their parents,” she says. And she couldn’t imagine using the old methods with this new generation that expects interactivity and give-and-take.

Counterintuitive as it may seem to some, Jones-Jackson thinks social media is leading the children of millennials to form stronger social bonds than previous generations, because they’re in contact with one another more outside of school. “They talk all the time,” she says. “They have more to say.” And when they’re having class discussions, the kids are more savvy about what’s going on in the world—perhaps another virtue of the connected life.

Other adults who are spending a lot of time with today’s kids, however, worry that they don’t respect adults. Debbie Cole, 56, has established multiple chapters of the MOMS Club, a national support group for mothers who are home during the day. “There seems to be a large swing to giving the children too much power,” she says. “There’s sometimes too much leniency with kids and giving them this inflated idea of their own place in the world.”

Experts say parents who put self–expression first may raise kids who grow up expecting to get what they want, when they want—in a consumer culture that already caters obsessively to instant gratification via the web. “There’s the implicit, hidden teaching that comes from the fact that things are instantly accessible,” says Jenny Radesky, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician at the Boston University School of Medicine. “And that becomes this expectation that things are going to be fed to us.”

For better or worse, technology is also keeping kids and parents more connected than they used to be; kids can now text when they get to school or soccer practice or home. At a certain age, the smartphone becomes a link to one’s children, just as it’s a link to work. Dottie Reed, head administrator at Camp Pemigewassett, a boys’ sleepaway camp founded in 1908, says devices are a bit like umbilical cords between young parents and their kids. Moms have even been known to pack a second device in their kids’ things, because they know the first one will be confiscated. “Parents who are so used to being in touch with their kids throughout a day know they are breaking that connection for a few weeks,” Reed says. “It’s hard for them.”

As for the kids, most are ready to unplug, even if it can take a little prodding. Sometimes the boys use the camp as the “bad guys,” Reed says, so they have an excuse to give their families and friends as to why they’re offline. “What that does is that frees them up to just relax and play, the sort of thing that maybe doesn’t happen as much in a life in which it’s a little bit too easy to pick up a device.”

Perhaps the biggest unknown is what it will mean for this new generation to have had every life milestone—from birthdays to baths—documented extensively online. “Children growing up will have multiple identities,” says the University of Michigan’s Schoenebeck. “They will have a more public one that has been created by their parents, that’s been cultivated by grandparents. But they will maintain a more personal and private independent identity as well.”

Schoenebeck doesn’t think it’s particularly worth fretting about what this will mean for them—in part because who knows what new thing will have come along and revolutionized the world in 10 years, but also because the kids they’re growing up alongside will have had the exact same thing done to them.

The Hayeses are sitting in a booth across from Astral and Defy at Veggie Grill in Corte Madera, Calif. It’s the day before their fifth birthday, and the boys are drawing pictures of food on two pages of the same notebook with little golf pencils. Once everyone decides what to order, which takes a little while, Lucas jots notes on his phone and goes up to the counter. Kenya speaks about how she feels guilty for having to work at home in front of her kids. And she explains how they got their names, which were inspired, respectively, by the stars and the act of challenging what is considered possible.

“I just want them to be unique,” Kenya says. Toward the end of the meal, Defy starts negotiating. He wants to skip the rest of his vegan burger and go straight for the carrot cake. The situation is settled when nothing else is eaten at all. A little bit later, Kenya picks up her smartphone—which she’s been checking throughout the meal for work emails and texts—to take a snapshot of them drawing together.

“I just have to take a picture,” she says, to no one in particular.