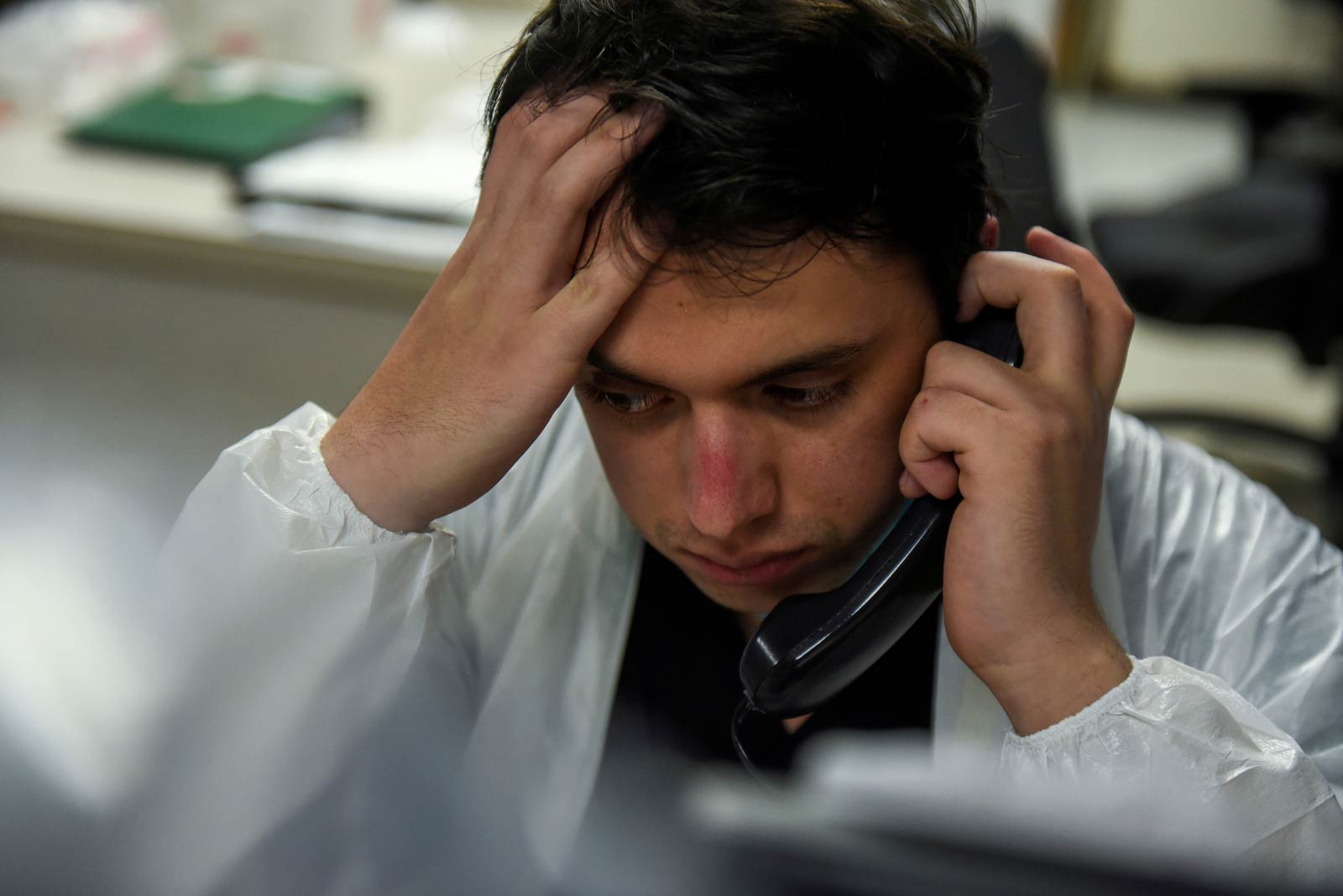

The outbreak in the Seattle area marked the known American arrival of the virus and showed how deadly the disease would become for the elderly. Life Care Center of Kirkland, Wash., where resident Judie Shape can be seen speaking on the phone with her daughter, Lori Spencer—who had to stay outside because of quarantine protocols—would eventually be linked to more than three dozen deaths. That, though, would turn out to be just a sliver of the more than 170,000 deaths related to nursing homes and other long-term care facilities that have been reported nationwide through the course of the pandemic. “One year later, I have freedom and health,” says Shape, who was recently vaccinated. “My concerns and wishes are for those still fighting their heavy battles.” After such a difficult year, “I must say my mom has been one incredible trooper,” Spencer says. “We’re all going to put this behind us. One of the things I’m looking forward to is being able to pop in and just have a cup of tea with mom, just to sit and spend some time. The value of that can’t be understated."

David Ryder—ReutersWhen Victor Llorente arrived at the New York Stock Exchange to photograph a new deep-clean regimen instituted due to the pandemic, he was provided with a gas mask and goggles to wear while biohazard disinfectant was sprayed on all surfaces inside. “I wanted the viewer to feel the surreal atmosphere that I felt while I was there,” says Llorente, who worked into the night. He arrived when there were still brokers yelling on the floor, and left around 3 a.m. “This is probably the last memory I have of a room filled with people before the world changed to what it is now,” Llorente says. “It’s crazy to think how they were just cleaning the floor with plans to reopen the following week. It really shows how we misunderstood the severity of the situation.”

Victor Llorente—The New York Times/ReduxThe tip came from a friend: as classes at the Canterbury School in Greensboro, N.C., moved online, educators were bagging up students’ belongings while the facility was cleaned and sanitized. “I knew it would make a photo,” says Khadejeh Nikouyeh. “I called the school and they welcomed me in.” There, she found teacher and administrator Kelen Walker packing the contents of students’ lockers into trash bags. “Looking back at this image and a few others I’ve made during the pandemic, I realize for the first time in my career that I was actually documenting history, not just daily news,” Nikouyeh says. “What we do matters more than ever, especially as photography staffs shrink across the country.”

Khadejeh Nikouyeh—News & Record/APAs the virus evolved into the largest international disruption in a century, Father Matthew Fish of Holy Family Catholic Church in Hillcrest Heights, Md., was among those who sought out ways to meet the needs of observant community members while their houses of faith were closed. Using an old curtain, duct tape and other found materials, he created a makeshift confession booth in a driveway next to the rectory that preserved privacy and anonymity while also allowing for social distancing. “It was a beautiful day with gusts of wind and the priest had to secure the setup with a couple of 10 lb. weights,” says photographer Evy Mages. “From a distance, I observed the faithful pull up in their cars and imagined them unburdening their soul and receiving a blessing.” A year later, this scene reminds Mages “how simple acts of kindness can offer solace, support and human connection.”

Evy Mages—WashingtonianTod Seelie was in Las Vegas to photograph the shutdown of the Strip when he heard that a homeless shelter had apparently closed temporarily due to a positive COVID-19 case. Guests were moved to a parking lot. “Not far from this location were literally rows of empty hotel rooms that could have been used to temporarily house these people,” he says. “It would have required funding and effort, but I don’t think it would have been outside the ability of a city like Las Vegas to pull together. We as a society make decisions around our priorities, and I think this image lays clear what some of those priorities were during this pandemic.” When others see this photograph, he adds, “I hope people see a situation and realize it was avoidable.”

Tod Seelie—The Guardian"When the first wave hit our area," says Danny Kim, a paramedic at Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck, N.J., "some of my coworkers were optimistic, saying this will only last three months. Others were saying two or three years." In the early days of the pandemic, he recalls, “whenever I saw a patient on a ventilator or about to be intubated”—as was the case here—“their outcome was going to be very poor, most likely death.” New Jersey would go on to record nearly 24,000 deaths. “The past year was a blur because I was working so much. I finally stopped because I got COVID-19 right around the time when the first vaccine became available,” says Kim. “It gave me time to think that I need to work less for my own well-being. With vaccines available and cases trending down, I feel optimistic for the future.”

Danny Kim for TIMEIt became a ritual. As winter turned to spring, President Trump and his task force would hold a nightly briefing for Americans on the status of the pandemic and the government’s response. For the Washington, D.C., press corps, that meant working in the same room in the White House, under the same limitations, with many of the same people, day after day. “It was a time for a photographer to be creative,” says Tom Brenner. On the last day of March, Brenner lucked out with a front-row position and was able to capture the arrival of the President and the team tasked with combating the virus. Trump and Dr. Anthony Fauci, the country’s top infectious disease expert, were at odds—as they would be throughout the year—over facts, the best course of action and the messaging of that response. “You can see the diminished relationship, the tension,” Brenner says. “He was just waiting for him to come out.”

Tom Brenner—ReutersIt was only a matter of days between New York City recording its first known death from COVID-19 and the region’s grim ascension to a global epicenter. “We all had been hearing how bad the numbers were and how overwhelmed the hospitals were, as well as the instructions to stay home,” says photojournalist Philip Montgomery. “So you had all that factual information but no visual confirmation.” After entering a Queens public hospital’s emergency room, he looked over at his assistant: “Our eyes were just huge and starting to water up and tear,” he remembers. “This was an enormous situation, and we just had no preface to prepare us for what that was.” Later, inside the Lincoln Medical Center in the Bronx, he watched as Dr. Sherry Melton, center, moved a gurney after transferring a patient to the intensive care unit. Montgomery aimed to make a photograph that conveyed the urgency of the moment. “It was just one patient after another. These men and women are there every day, and they’re exhausted,” he says. “This was the reality. This was the first peak.”

Philip MontgomeryTwo coffins. That’s about how wide the trench was dug on Hart Island—the strip of land in the Bronx that, until 2019, had served as New York City’s potter’s field—as the pandemic’s toll worsened in the New York region, mortuaries were overwhelmed and the need for a temporary burial site grew. “We had heard rumors this was going on and we knew that we needed to get these images, but we also knew that what was happening there was being denied vehemently,” says photographer John Minchillo. When stronger collective action could have helped stave off the deadliest scenarios, mixed messages and disinformation were rampant. “It was a desperate sprint to try to do my little bit and show this is happening,” he says. “If you won’t read the story, look at the picture. How can you deny the picture? It was really painful to go through the year trying to convince people that something is real when it has a body count.”

John Minchillo—APLocal news reported about 100 protesters had assembled outside the Ohio Statehouse in Columbus during Republican Gov. Mike DeWine’s update on the state’s response to the pandemic, upset about an ongoing stay-at-home order and that non-essential businesses remained closed. At far left is Ohio Senate candidate Melissa Ackison. Earlier that morning, while her husband was conducting a land survey, the authorities were summoned and he was asked to prove his job was “essential.” With schools closed, her son was with him. As Ackison tells it, “something really snapped” in her mind. Combined with the postponement of the state’s Republican primary—a race for which she had been preparing for more than a year—and she says it’s clear why she reached a “tipping point.” Ackison looks “enraged,” in her words, “because that’s frankly what I was.” The reaction to the photograph was swift and intense. “Everything from folks who felt the same way, who were losing everything, and then you had the opposite,” she recalls. “People wishing death on me. ‘You should go kill yourself.’ ‘I hope you die.’ ‘I hope you don’t get a ventilator.’ Things like that, by the thousands. People who didn’t take the time to understand how you could get to a moment like that.” At one point, Ackison admits, “I finally just had to walk away from it because it was just so toxic.” Nearly a year later, she doesn’t regret that scene. “I would want people to know this image is a person who has been kicked around, or certainly feels like they’ve been kicked around, by the government and politicians on both sides of the aisle.”

Joshua A. Bickel—The Columbus Dispatch/APA year after the global epicenter of the pandemic settled into New York City—overwhelming its hospitals as thousands of people died, brutally foreshadowing a horror that would sweep America—Kyle Edwards has a deeper appreciation for life and the fragility of his own mortality. During the height of the first wave, Edwards was often tasked with transporting the bodies of COVID-19 victims to temporary morgues outside Wyckoff Heights Medical Center in Brooklyn. “In my 18 years working here, I never had to visit the morgue so much,” he says. Like many members of his team, he contracted the virus. His proximity to death—and the frequency of it—inspired Edwards to get his affairs in order for his family. “My fear,” he admits, “was having my son grow up without a father.”

Meridith Kohut for TIMEAs cars lined up at the Utah Food Bank’s mobile food pantry at the Maverik Center in West Valley City, outside Salt Lake City, volunteers told Rick Bowmer it was the first time they had seen that many people seeking this sort of assistance. “It was a time of uncertainty,” the photographer says. “People were dying or losing their jobs and businesses were being closed.” Bowmer focused on the sheer scale of the demand and putting it into perspective as the national death toll climbed. “We’ve all seen the pictures from the Great Depression,” he says, “and here it is during our lifetime.”

Rick Bowmer—AP“Rescheduling or canceling a wedding feels like a trivial matter in the context of a global pandemic,” says photographer Maggie Shannon, “but it does have a personal impact on these individuals. I wanted to lift them up.” As spring wore on, she contacted wedding planners in the Los Angeles area to see if they would connect her with couples who had decided to cancel or postpone their weddings. That’s how she met Judi and Eric, the couple in the center of this photograph. The couple had initially postponed their wedding until 2021, but Judi was concerned her elderly father, who was undergoing treatment for a health ailment, would not be able to attend their new date, and she wanted him to walk her down the aisle. So, instead, they planned a small ceremony in May, which would ensure Judi’s father would make it. “A neighbor decorated their driveway with rose petals and another served as their officiant,” Shannon recalls. The bride had sewn a mask to match her dress. “These tiny moments of joy are easily forgotten when there is so much suffering.”

Maggie ShannonLidia Herrera’s pleas weren’t working. Her brother, Miguel, was dying in a Brooklyn hospital but it wasn’t safe for her to be by his side, she was told. Finally, on the day when the 63-year-old would be disconnected from life support, Herrera was allowed inside. “It wasn’t sufficient to just see him through a cell phone,” she says. “I needed to touch him, to stroke his head.” Wearing protective gear provided by photographer Meridith Kohut, Herrera said her final goodbye. As the year went on, the void Miguel left behind grew. A brother he lived with wasn’t immediately told, so as not to impact his own fragile recovery from the virus. Miguel’s remains were repatriated to Mexico in July, but many were forced to grieve remotely. Then, the holidays. “He was always with us, always taking care of us during Christmas and on New Year’s Eve,” Herrera says. At midnight, their tradition was to hug one another. This year, there was no embrace. “I dream about him a lot,” she says. “Sometimes I get sad, because he is always sick in my dreams.”

Meridith Kohut for TIMEWhen Jacqueline Venner, a beloved union representative at Wyckoff Heights Medical Center in Brooklyn, died of COVID-19 in April, her family had to wait more than two weeks for a brief, two-hour time slot at a Queens funeral home in order to hold her funeral. It was still early on in the pandemic, before much of the public knew how the virus spread. The exercise of mourning was changing in real-time. At that point, it meant fewer people could attend—capacity at Venner’s service was limited to 10 people, including photographer Meridith Kohut—and less time to grieve together. A sign posted on the door discouraged mourners from touching one another. When Erica Davis reached back to hold the hand of co-worker Marsha Williams, a patient-care coordinator at Wyckoff’s women’s health center, “it really struck me,” Kohut says. “It was so symbolic of this past year and how we’ve all been struggling, often in isolation, as well as the ways we’ve all tried to comfort each other, albeit from a distance.”

Meridith Kohut for TIMEFrancisco James, a resident funeral director at Leo F. Kearns Funeral Home in Queens, is shown here in an overflow room used to apply makeup to the deceased before viewings and burials. Every available space in the building, and a refrigerated container behind it, was used to store bodies. “I was only at work for about three weeks when this happened,” says James, who was an intern. “I remember walking in one Friday and my boss said, ‘you’re not going to believe this, but we had about 300 first calls last night.’ A ‘first call’ is when the family notifies the funeral home that a loved one has passed away. My eyes just exploded because I wasn’t sure what to expect.” For about three months, James says, it was nonstop. “I was working six days a week, 14-hour shifts, to accommodate all the families and the bodies. We were picking up an average of 14-15 bodies per day.” His main concern was bringing the virus home to his family. “We were just so exposed to it,” he says. “My boss told me what I did in that three months is the amount of work we would have done in three years.”

Peter van Agtmael—Magnum PhotosGet TIME delivered straight to your home.

It was a surprise. A few days earlier, Mary Grace Sileo’s son invited his parents over for Memorial Day Weekend. They hadn’t had physical contact since the lockdown began. Shortly after Sileo and her husband arrived from Staten Island to Wantagh, N.Y., they were ushered to the backyard, where a plastic drop cloth was hung from a clothesline. “Go ahead,” her son encouraged. “Hug the kids.” It went on for a while. Everyone took turns. Sileo noticed Al Bello taking pictures, “but I was just caught up in the hugging.” At one point, she was photographed hugging her granddaughter, Olivia Grant, seen here. As the pandemic raged on, similar scenes would play out around the world. The family hasn’t recreated it since then, Sileo says. “It was a wonderful day. Just wonderful. These hugs, they were so therapeutic. Water on a dry plant.”

Al Bello—Getty ImagesAs spring turned to summer, America’s streets swelled with protesters uniting against systemic racism. In Philadelphia, after his ceramics classes were canceled, Isaac Scott shifted to photography. On the steps of the city’s iconic art museum, he photographed a group of protesters laying on the ground for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the initially reported amount of time that a white police officer fatally pressed his knee into George Floyd’s neck about a week and a half earlier in Minneapolis. “You could feel the weight of the moment and the silence made you painfully aware of how long that time on the ground really was,” Scott recalls. “Some people were moved to tears as they got back to their feet. Looking at the image now, I feel a deep sense of solidarity with the people. I see the act as a form of radical empathy.” Public-health experts feared the gatherings would significantly spread COVID-19. Scott worried, too, but saw protesters were “disciplined and adamant about mask-wearing.” The anticipated viral surges never materialized.

Isaac ScottIt was Father’s Day. As Nash Ismael, 20, and his sisters Nadeen, 18, left, and Nanssy, 13, visited the gravesite of their parents at White Chapel Memorial Park Cemetery in Troy, Mich., he placed his arms around them. Nameer Ayram and Nada Naisan, who brought the family from Iraq more than eight years earlier, died as a result of COVID-19 within weeks of one another in April and May. “I was always spoiled from my parents so now I can’t deny my sisters anything they want. I don’t really treat them like I’m their parent. Sometimes I ask Nadeen to clean the house, but it’s hard,” Nash says. “Looking back, I thought COVID was like catching a cold and I didn’t think it was that serious. I wish I spent more time with them both. We’re living day by day. I’ve grown a lot and now we are much closer as a family.”

Salwan Georges—The Washington Post/Getty ImagesPlastic shields surround the desk where 6-year-old Aven Mullins works inside Wesley Elementary in Middletown, Conn., as the school district instituted a pilot program that would safely bring kids back to classrooms—and their parents back to work—with an eye toward the fall. In the weeks after this photograph, Aven went back to a hybrid learning model: two days a week in person and three days with virtual lessons, says her mother Anna Terry, an educator at a nearby high school. Terry’s 69-year-old mother “stepped up” to help on the days when Aven and her sister were learning at home, she says. “I would have had to leave my job if not for her.” Aven has done “remarkably well” and “her teacher has done an amazing job with keeping her engaged and encouraging her to do her best,” Terry says. But, she misses her friends. In mid-March, Aven and her sister will go back to in-person classes full-time, and get to spend time with friends they have not seen since last year.

Gillian Laub for TIMEIn Chicago’s Cook County Jail, photographer Dave Kasnic was shown how the pandemic was affecting the facility and those incarcerated there. During the tour of the jail—which experienced one of the largest clusters of confirmed cases in the spring—there wasn’t much time at each location, “so you have to be smart and work diligently,” Kasnic says. Outside one cell, Kasnic asked his minders if he could photograph a man leaning against the door, peering out. They agreed, as long as his identity was obscured. Kasnic thought to himself, “so how do I photograph this individual with dignity?” He told the man he was with Chicago magazine and the theme of the story. People yelled “show how they’re treating us in here” and “photograph me” as Kasnic made this portrait. “This individual represented so much more than just himself in that situation,” he says. “His body language, his eyes, the mask, the light, everything culminated into a picture that represents the hell that incarcerated individuals deal with during the pandemic.”

Dave KasnicMaika Alvarez, a certified nursing assistant, helps Jose Montoya speak with his daughter Lillie Ortiz through FaceTime at the Canyon Transitional Rehabilitation Center in Albuquerque, N.M. Months earlier, the nursing home was converted into a facility specifically for COVID-19-positive residents like Montoya. Relatives were not allowed inside. Wearing a Hazmat suit and photographing through layers of glass—eyeglasses, goggles, a face shield and the camera lens—Isadora Kosofsky says she “lingered for hours” in rooms to capture these types of intimate scenes. "Thank you for caressing my dad’s head," Ortiz told Alvarez, who called Montoya “grandpa,” Kosofsky says. “Subtle gestures of love and care can provide some relief for family members on the other side of nursing home walls,” she adds. “Families fear that their loved one is overlooked when they cannot be present to observe and control.” Montoya, a World War II veteran, died on Sept. 13. He was 94.

Isadora Kosofsky—The New York Times/ReduxAs Maricopa County constable Darlene Martinez escorted a family from their Phoenix home, thousands of court-ordered evictions were being carried out nationwide. State and federal protections were in place for renters economically impacted by the pandemic, but navigating them wasn’t easy—if renters even knew about them. “She calmly explained to the tenant that she had to collect her belongings,” says photojournalist John Moore, who shadowed Martinez for weeks. “She even helped the tenant to find her cats.” The woman shown exiting her home told Moore a familiar reality: “She had been out of work for six months already, as she had to stay home and supervise her childrens’ remote learning,” he remembers. “She had never gotten around to filling out the necessary documentation. Although she had been notified of the impending eviction, she had hoped that somehow it would not actually happen.”

John Moore—Getty ImagesAnna Moneymaker was sitting in Lafayette Square, across the street from the White House, waiting to hear from her editor when President Donald Trump would be returning from a four-day stay at Walter Reed Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., where he was treated for COVID-19. When she got a text, she went over to the White House to capture Trump’s arrival. “His tweet that he posted right before leaving Walter Reed—‘Don’t be afraid of Covid. Don’t let it dominate your life.’—was on my mind as I saw him walk across the South Lawn,” she says, “and the whole moment felt as surreal as when I saw him go to Walter Reed days earlier.” Once she felt like she had a satisfying composure of Trump on the Truman Balcony, the president began removing his mask in “this slow, delicate way.” Not long afterward, Moneymaker and the other photographers were ushered away. “For all those who covered the White House that weekend, the whole period of time was a bit intense, trying to dig for the truth about the president’s health,” she says. “I never took my finger off the shutter.”

Anna Moneymaker—The New York Times/ReduxKendrick Brinson has been photographing the denizens of Sun City, Ariz., for more than a decade. As the pandemic roared in the American West, Brinson was anxious to check in with the area’s active retirement community. During the trip, she caught up with the Sun City Poms, a squad of cheerleaders in their 60s, 70s and 80s. Instead of their standard practices and performances, which were off-limits, Brinson was shown something else: in one member’s backyard, they hula hooped while remaining socially distant. “I was happy that these women had found a way to adapt and to do what they loved together again during such a stressful time,” Brinson says. “It reminded me how important community is for mental health.”

Kendrick BrinsonOn Thanksgiving, as national grief and mourning rose to levels unseen in generations, families gathered in smaller circles than normal. Many had an empty seat at the table. After photographer Erika Larsen read about younger Americans whom the virus had taken—including Adam Hergenreder, who died at age 32 from complications of COVID-19 in July—she reached out to Adam’s mother, Elaine Minichino, and asked if she could spend the holiday with the family. “They didn’t ask, ‘what do you want from us?’ They understood why I was there,” Larsen says. She just listened and observed, learning more about Adam and how Minichino cared for him. As dinner neared, the table was set. “They ate, and toward the end, she set another place setting for me and I sat with them. She left his plate there for him.” As a storyteller, Larsen says, “we forget there is this collective sense of telling something common that’s important for people. If there wasn’t an outside person there, they might have stayed more silent.” For Minichino, “it let Adam be real. It let his death be real, and his life be real.”

Erika Larsen—ReduxGabriel Cervera Rodriguez, 25, has worked in the COVID-19 unit of Houston’s United Memorial Medical Center since his internship began last summer. He sees patients upon admission, develops treatment plans and updates families on patient statuses. If the time comes, he informs them of a loved one’s passing. “I was taking care of this very sick patient who had been transferred to us via helicopter from a small town in Texas a few weeks before. The family wasn’t able to see them for several days because of policies that restrict visitors during the pandemic,” says Cervera Rodriguez. “That morning when I arrived, I was caught between two patients dying in rooms across from each other. One of them coded and we immediately started resuscitation protocols. While we were working on this patient, a nurse from the other room yelled: ‘the patient doesn’t have a pulse!’” It was the one he had been taking care of. “I activated the code to bring more people in to help and started working on both patients. After several minutes of trying, we called the time of death,” he remembers. Then he had to notify the family. “It was the same time we usually spoke. They were expecting my call. I picked up the phone and my whole body was shaking.” Each time, he aims to be compassionate, brief and to the point. “After I hang up,” he says, “sometimes I’m speechless, but I have to keep providing my best for those who are fighting. I try to keep in mind at least one nice detail of every patient who has passed.” Cervera Rodriguez thinks often about his family in Mexico, fearing the same may happen to them: “Sometimes I call them just to hear their voices.”

Callaghan O’Hare—ReutersJesse "Jay" Taken Alive died of complications related to COVID-19 on Dec. 14, about a month after the disease took his wife of nearly 46 years, Cheryl Taken Alive. Their deaths were a major blow to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, to which they belonged. “Ina” and “Ate,” which respectively mean “mother” and “father” in the Lakota language, were inscribed on their caskets. “He was a teacher and beloved member of the community, along with his wife,” says Richard Tsong-Taatarii, who received permission to photograph a portion of the burial south of Cannon Ball, N.D. “The side-to-side burial of the couple was something I had not seen in the funerals I attended on the reservation.” For Tsong-Taatarii, it has been crucial to highlight the pandemic’s disproportionate toll on communities of color. “This becomes part of the historical record that has to be acknowledged,” he says, “and should not be forgotten.”

Richard Tsong-Taatarii—Star Tribune/Getty ImagesDuring the insurrection at the Capitol, where Christopher Lee photographed U.S. Capitol Police watching rioters through a smashed window, he says “there was a moment when a group of rioters grabbed me and forcibly pulled off my mask, accusing me of being ‘fake news,’ threatening physical harm and ridiculing me for taking the pandemic seriously.” Days later, Lee tested positive for COVID-19. “While in isolation, my mind told me to expect the worst,” Lee says. “Considering I spent the majority of the last year photographing how horrible this pandemic is and am still reconciling with what happened at the Capitol, it put me in a difficult headspace.” His mind and emotions, like many other Americans, “are slowly but surely navigating the fog” in which this country remains. “This feeling of anxiety, loss and anger is something that many people of color in marginalized communities deal with,” he adds. “Being back in my home state of Texas, I have felt weary of any pro-Trump logo I see being worn. I wonder if they were one of the rioters sporting the state’s flag in Washington, D.C., threatening me.”

Christopher Lee for TIME“I’m just being patient for my turn,” says Robert Gauthier. On this day, not quite a year after the dawn of the pandemic in America, the photographer was directing a drone to capture a winding line of drivers waiting their own turns to get a COVID-19 vaccine shot near Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. Gauthier had covered his fair share of potential superspreader events over the past year—dozens of protests, the baseball World Series, and other large gatherings—that left him thinking, “I’m gonna get it now.” The national rollout across the country hasn’t always been orderly. To Gauthier, it’s worth the wait. “I’m 59,” he says. “I’m looking forward to the day I get to sit in that line.”

Robert Gauthier—Los Angeles Times/Getty ImagesThe arrival of Joe Biden to the White House marked the return of a Consoler-in-Chief. Where his predecessor lacked empathy, Biden is a natural. That much was clear on the grim occasion when the United States hit 500,000 deaths as Biden—alongside First Lady Jill Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris and Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff—held a candlelight memorial. “He wanted to honor everybody who had passed away, and honor the families that are living through it now,” says photographer Doug Mills. “When it was over, everybody kind of looked at each other, a little bit speechless, like, ‘Wow, that was a powerful moment.’” In the wake of “one of the most stressful years” of Mills’ career, “it feels like a new beginning here.” Often in politics, he adds, “the goal post gets moved because things are getting worse. This one is not. This one is getting better. There’s a lot of light at the end of this tunnel.”

Doug Mills—The New York Times/Redux

;

;