The Childcare Crisis

“I can afford to have a child, I just can’t afford to pay for their care for the first three years of their life.”

— Amy Deveau, Massachusetts mother“My employees have to rely on food stamps and child care assistance themselves, because... I can’t pay them a living wage.”

— Deb VanderGaast, Director of Tipton Adaptive Daycare in Iowa“If I'm a nanny, how am I going to afford a nanny?”

— Jasieth Beckford, New York City mother and nannyand Belinda LuscombePhotographs by

Anastasia Taylor-Lind

These photographs were shot in partnership with Fotografiska New York over 5 months; an exhibition will be on view at the museum in 2020.

Ashley Alcaraz remembers when she started to regret entrusting her infant daughter Paysen to an unlicensed in-home day care when she returned to work. She found out her daughter had been sleeping on the floor in a house where dogs and cats roamed around, and she worried that older toddlers might step on the baby. After her request that Paysen sleep in a crib was ignored, she pulled her daughter out, but the day care had been the most affordable nearby option and Alcaraz had already used up her allotted three weeks of paid maternity leave—in addition to three weeks of unpaid leave—from the Iowa hospital where she works as an X-ray technologist. Desperate for trustworthy care, she enrolled Paysen at Tipton Adaptive Daycare in Tipton, Iowa, which was more expensive, at $640 per month—about 18% of her income—but the most affordable licensed childcare available. It was worth the cost, Alcaraz felt, because she could tell the staff cared about her daughter, greeting the 16-month-old by name each morning.

Still, Alcaraz, 25, and her boyfriend now often run out of money for groceries while paying the day-care bill. “Right now, it’s paycheck to paycheck,” Alcaraz says. “It’s a struggle.”

Affordable childcare is at once one of the most tantalizing promises of contemporary American life, and the most broken. Our modern economy cannot function without a system for the nurturing of our youngest citizens—as of 2017 there were nearly 15 million children under 6 in this country with all available parents in the workforce. But for everyone except the very wealthy, childcare is ruinously expensive. In 28 states and the District of Columbia, one year of infant care, on average, sets parents back as much as a year at a four-year public college, and nationally childcare costs on average between $9,000 and $9,600 annually, according to the advocacy organization Child Care Aware. Many parents spend far more. In Boston, 36-year-old Amy Deveau will spend $21,000 this year, a third of her salary, on day care for her 2-year-old—more than she would spend on tuition and fees if her daughter were enrolled at the University of Massachusetts. “What’s crazy is that you have 18 years to plan for your child to go to college and put together your savings accounts and work on loans,” Deveau says. “You don’t have the luxury of having 18 years to plan for day care.”

Nearly 2 million parents had to leave work, change jobs or turn down a job offer because of childcare obligations in 2016, according to an analysis by the Center for American Progress (CAP), a left-leaning think tank. America’s rickety childcare infrastructure is a drain on parents, who lose up to four times their salary in lifetime earnings for every year they’re out of the workforce, but even more of a drag on the U.S. economy, costing it $57 billion every year in lost earnings, productivity and revenue, according to a report published in January by ReadyNation, a nonprofit advocacy group of business executives.

The burden of childcare beleaguers economic growth on two fronts, tamping down the productivity of citizens as well as pushing more of them onto taxpayer-sponsored programs such as SNAP (formerly known as food stamps), WIC (benefits for low-income mothers) and TANF (welfare). Cruelly, it’s usually the more impoverished who find it most difficult to afford childcare and thus advance their careers and become more prosperous, further stymieing economic mobility. But perhaps the most damaging punch that unaffordable childcare is dealing to the U.S. economy is its diminishing of future generations. Young Americans are having fewer children—the 2018 birth rate was the lowest in 32 years—and according to a survey conducted by Morning Consult for the New York Times, the expense of childcare is the No. 1 reason.

Yet caregivers can’t just charge less. So confounding is the childcare economy that despite the sticker shock for parents, looking after children remains a very poorly paid job. Deborah VanderGaast, the director of Tipton Adaptive Daycare, where Alcaraz sends Paysen, says the business model just isn’t sustainable without subsidies. VanderGaast, 51, charges $160 per week for full-time infant and toddler care—a rate she tries to keep affordable for parents—but she is barely breaking even. She says about 25 families have past-due balances. She sets up payment plans and helps parents with childcare assistance applications. Sometimes she asks them to help her with odd jobs at the day care to pay down their debt.

“It must appear I’m a terrible business manager. I know that common sense would be to kick out a family when they get behind on their bill,” she says, but she understands families are struggling. State licensing requirements that ensure safety and quality mean she can have no less than one worker for every four children under 2, and one worker for every six children under 3—she pays 15 employees, starting at $7.25 to $10 an hour. She can’t skimp on health and safety inspections, nor can she cut back on food, knowing that many of her parents already rely on food stamps. She loses money on every infant and 2-year-old in her care. After doing payroll one week in October, VanderGaast says, her business bank account had $9.30 remaining, and she hadn’t yet ordered the day care’s groceries.

At the same time, she knows she isn’t paying her staff enough: “My employees have to rely on food stamps and childcare assistance themselves because they can’t afford childcare because I can’t pay them a living wage.” Ten of the 15 workers have second jobs. Turnover is high enough that she finds herself training new people nearly every week. She doesn’t blame workers for leaving. “Walmart pays better, McDonald’s pays better, the grocery store pays better,” VanderGaast says.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) estimates that nearly 1.2 million people are employed in childcare in America, not including the countless number who are self-employed. For those who show up on the books, the median annual income is only $23,240. “There’s a huge demand for unskilled workers who are willing to do these jobs,” says Aparna Mathur, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. Ideally, positions would be filled by highly skilled teachers with early-childhood education degrees. “You’d think the market should fill that gap by enticing workers with higher wages, but for some reason that doesn’t happen,” Mathur says. She points to the heavy regulations of the industry—necessary to guarantee good conditions for kids, but a financial burden on childcare providers.

Kathleen Gerson, a sociologist at New York University who studies families and work, calls caregiving a “canary in the coal mine” for other socioeconomic challenges in America. “It’s warning us of not just a care crisis, and a childcare crisis, but a larger crisis of what it means to live a sane and balanced life that allows people both to find dignity in work and also build the strong, stable families that they hope to have,” she says.

Indeed, what feels like a private calamity in each home is actually the result of some of society’s most thorny unsolved issues—the often ignored rights of immigrant workers, the persistently uneven division of labor between men and women, inequalities based on race and socioeconomic status, and the glass ceiling women face in the workplace. Successive presidential Administrations have done little more than enrage parents with the lack of progress on the issue, but a growing understanding of the broader economic impact of the inefficient childcare system is finally leading to more urgency to find a remedy. President Trump’s Administration has doubled the child tax credit and the size of grants given to states to subsidize childcare. As the 2020 presidential race heats up, a new raft of suggestions has been launched, from Senator Elizabeth Warren’s well-defined universal-childcare program, to commitments from Kamala Harris, Beto O’Rourke, Amy Klobuchar and Cory Booker to enact the Child Care for Working Families Act, to Trump’s proposed one-time $1 billion injection to build out childcare infrastructure. The only consensus seems to be that the current situation is untenable. As Ivanka Trump, who is leading the Administration on childcare reform, tells TIME, “You’ve got a fundamentally broken system.”

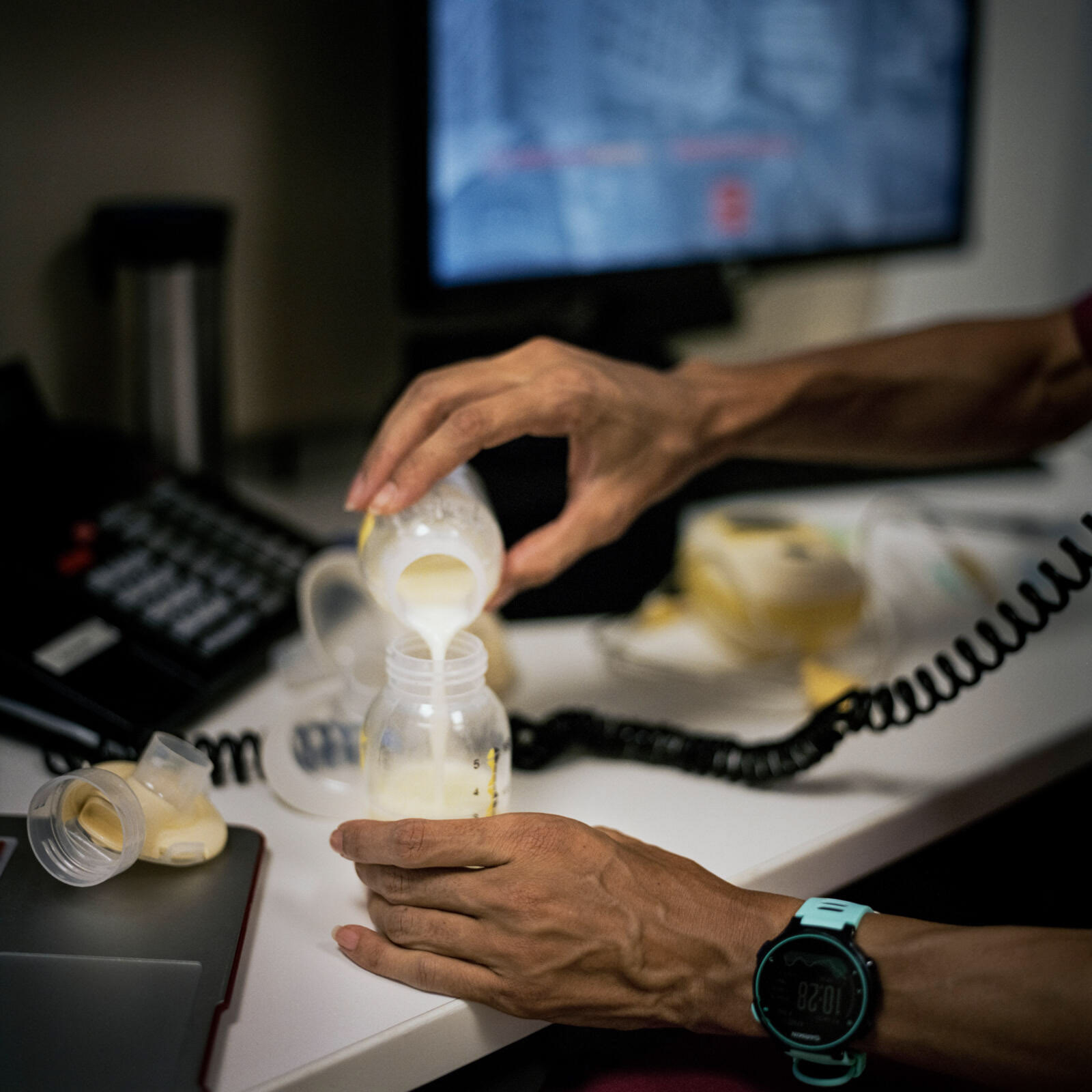

Wakenda Tyler knew child care would be expensive, but needed to keep her job as a surgeon to support her family.

“It takes a village to raise a family, and we don’t live in a village anymore,” she says. “We have to hire the village.”

“They do the work that makes our lives possible,” Rachel Kahan says of her nanny, Annie Nabbie.

Charlotte, a single mother who declined to use her last name, relies on a 24-hour day care for parents who work the night shift. When she drops Amina off, a caregiver reassures the children:

“The sun goes down and when the sun comes up Mommy will be here.”

To escape the paycheck-to-paycheck cycle, Alcaraz is considering a new job that would pay more but require her to move her family around the country every few months. She wants to have a sibling for Paysen, but without higher pay, she knows she won’t be able to afford the care. “You’d have to pay double, and that would be almost 45% of my income,” she says.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services considers childcare “affordable” if it costs no more than 7% of a family’s income. It’s a figure greeted with a dry laugh by most U.S. parents. Nearly two-thirds of them—and 95% of low-income parents—spend more than that, according to a 2018 report by the Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy at Brandeis University. And the problem has been growing worse for decades. More than 60% of families surveyed by Care.com in 2019 reported that their childcare costs had increased in the past year.

The federal government has twice attempted a comprehensive childcare program—similar to those in Sweden or France—only to later dismantle both efforts. The 1940 Lanham Act established a network of childcare centers after millions of women joined the workforce during World War II. The initiative was limited; 3,000 centers served 130,000 children, far fewer than the estimated 1 million children who needed care. But an analysis of the program by Arizona State University associate professor Chris Herbst found that it produced “sizable increases in maternal employment” for several years after the program was dismantled at the end of the war. At the time, there were calls for a permanent version. “Many thought [these centers] were purely a war emergency measure,” former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote in a 1945 newspaper column. “A few of us had an inkling that perhaps they were a need which was constantly with us, but one that we had neglected to face in the past.”

In 1971, Congress passed the Comprehensive Child Development Act with bipartisan support. The law would have developed a network of federally funded day-care centers, offering free care to the poorest families and subsidized care on a sliding scale for others. But it was derailed by President Richard Nixon’s veto, which warned it would divide families, diminish parental involvement and “commit the vast moral authority of the National Government to the side of communal approaches to child rearing over against the family-centered approach.”

Yet recent polls suggest that view no longer reflects the bulk of the populace. Most married couples with children both work outside the home now, and more than 75% of voters said they would support increased congressional funding for childcare and early learning, according to a CAP poll last year. Attitudes toward working mothers have also shifted. In 2018, according to the General Social Survey, only 28% of respondents believed that preschool children suffered if their mothers worked outside the home, down from about two-thirds in 1975.

And yet, the childcare landscape in America continues to resemble a curio store, full of options that are too expensive, too low-quality or that simply don’t work. Eventually one parent, usually the mother, gives up her job, often unwillingly. A 2005 Harvard Business Review analysis found that 43% of highly qualified women with children left the workforce. The effect of this resonates through decades. If a 26-year-old American woman who earns $40,508—the current average age for becoming a first-time mother, and the median salary for her age—leaves the labor force for five years for caregiving, she will lose more than $650,000 in wages, wage growth and retirement benefits over her lifetime, according to a CAP tool that calculates the “hidden cost” of childcare. And that doesn’t take into account the occupational toll: the lost years of experience and networking, the forgone promotions, the difficulties of re-entry.

Of course, many women would prefer to stay home with their children but cannot afford to do so. (Men’s willingness to work is not affected by children, studies show.) In 2018, according to the Institute for Family Studies, only 28% of married mothers with children under 18 said that working full time was ideal.

Nevertheless, very few households can get by on a single paycheck. Before she even got pregnant, Wakenda Tyler, an orthopedic surgical oncologist and the primary breadwinner in her New York City family, knew that leaving her job would not be an option. Her husband, David Van Arsdale, is a sociology professor who splits his time between New York City and Syracuse, about four hours’ drive away. They’re well paid, but Tyler needs to live close to the hospital, and New York is expensive. Van Arsdale initially balked at hiring a nanny, but neither parent could do their job without one. Jasieth Beckford now cares for the couple’s 10-month-old son every day, making $22 an hour plus overtime, totaling about $55,000 a year. “It takes a village to raise a child, and we don’t live in a village anymore,” Tyler told her husband. “We have to hire the village.”

Baby Doll Tucker works at the 24-hour day care.

Her 8-year-old son sleeps in their apartment upstairs, and visits his mom at work for homework help in the evenings.

Dionne Carter-Granger cares for children whose parents are having an emergency at the city-funded New York Foundling’s Crisis Nursery.

“These kids become our kids when they come in here,” she says; at home, her husband takes care of their daughter while she works.

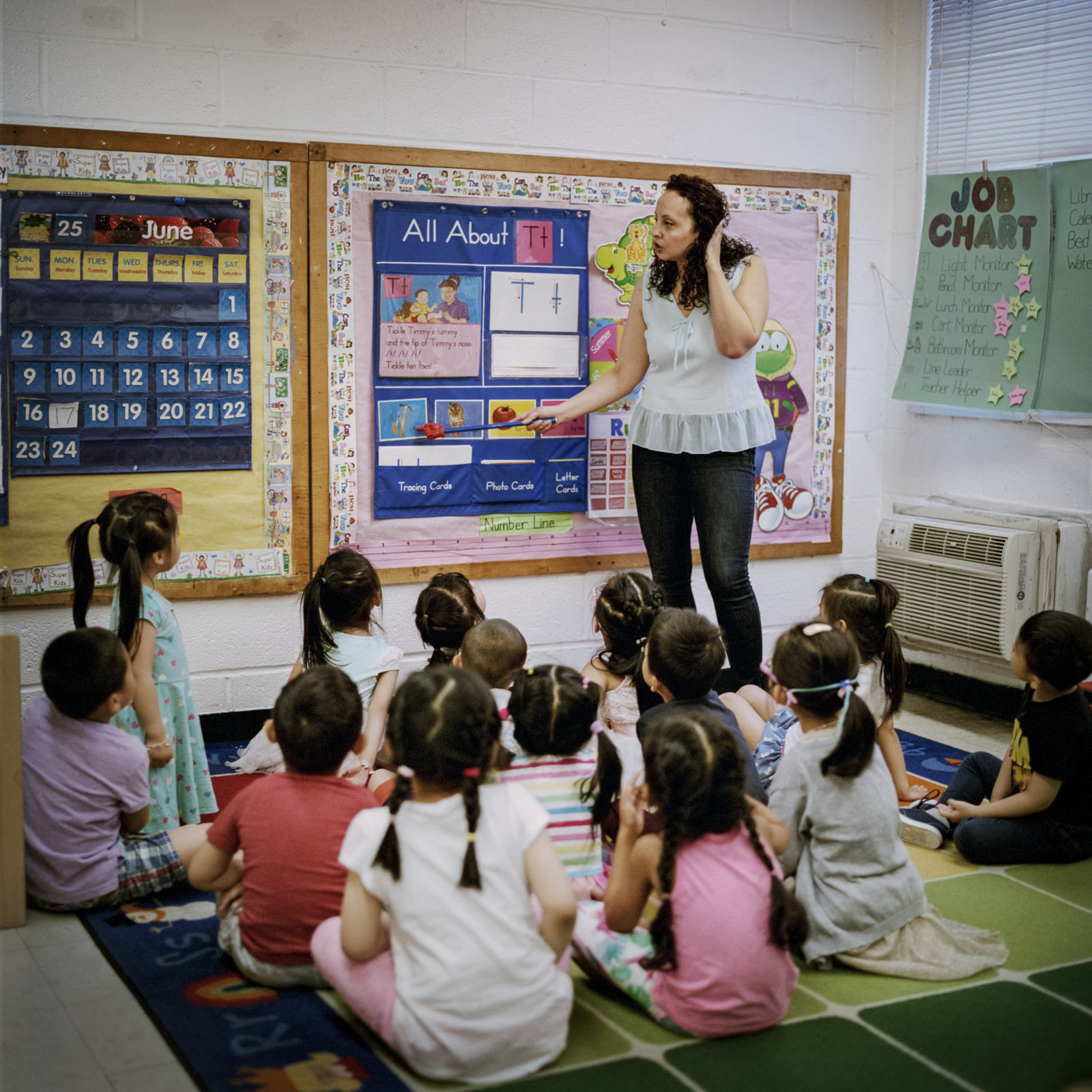

Stephanie Chang, who teaches 2- and 3-year-olds at Little Star of Broome Street in Manhattan, comforts Louis; Chang doubts she’ll ever be able to afford to have children of her own.

The village, of course, also has kids, who need their own village. Beckford started nannying when her 26-year-old son was 3, relying on her sister to raise him while she worked. “If I’m a nanny,” she says, “how am I going to afford a nanny?”

In Iowa, Shellby White works with 2-year-olds at the Tipton day-care center, teaching them to recognize colors, sounds and feelings, while her 8-year-old son is at school. She quit her previous job to care for her son when he was 2, because his grandmother became too ill to watch him full time, and the day-care centers in her area were either full or too expensive. She loves her job at Tipton Adaptive but earns just $10.05 an hour, making ends meet only because her husband works 75-hour weeks at his two jobs.

“We’re just seen as glorified baby-sitters, when we’re probably one of the most important parts of any working parent’s day,” says White, 29. “We’re keeping your kids alive, you know, we’re making sure they’re thriving.” And yet she sympathizes with parents. The cost of childcare is what makes her pause whenever she and her husband discuss having a second child.

Today, two-thirds of families with children under 18 rely on both parents to work, with many putting in longer hours. Demand for childcare is at an all-time high. But wages for childcare workers have remained largely stagnant, increasing by just 1% from 1997 to 2013 and barely keeping pace with the rising cost of living, according to a 2014 report by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment at the University of California, Berkeley. During that time, the average weekly cost of care for children under 5 more than doubled, according to the same report. Recently, childcare workers have seen a moderate increase in pay because of new minimum-wage laws, earning a median hourly wage of $11.17 in 2018. But childcare work is still among the lowest paid professions, and families of care-givers are more than twice as likely as other families to live in poverty, according to the Economic Policy Institute.

Many childcare workers are especially vulnerable to exploitation because of undocumented immigration status. Edith Mendoza—a Filipino immigrant and full-time organizer for Damayan, which advocates for migrant workers—arrived in New York in 2015 with the promise of a good job, only to find herself cooking, cleaning and nannying four children for about $4 an hour, 80 to 90 hours a week. “I was a slave,” says Mendoza, 53. “They treated me as not fully human.”

Even well-paid caregivers make sacrifices when it comes to their own children. When her son reached kindergarten, Beckford paid a retired grandmother to watch him after school in her home. Beckford paid the woman about $60 per week, and sometimes paid in groceries or sandwiches. It was not a licensed day care, and Beckford sometimes felt uneasy about the lack of regulation, but it was all she could afford. “My child suffered because I spent less time with him than I spent with other people’s kids,” she says now. “It’s the truth.”

Last year, Rachel Kahan co-signed nanny Annie Nabbie’s green-card application. When it was approved, both women stood in Kahan’s kitchen and cried.

Deki Choden left her two sons with family in Bhutan to work as a nanny in America. During their monthly phone call, Choden’s charge Jamison, left, asks her older son if he misses his mom.

No, he says. He needs to focus on his studies; he’s 12.

Jasieth Beckford has been a nanny since her 26-year-old son was 3. “My sister practically raised him for me,” she says.

The adage that the children are our future isn’t often thought of in terms of gross domestic product. But quality affordable childcare is directly related to the health of our future economy. A 2017 white paper from the U.S. Census Bureau that followed more than 2 million children for five years found those who were in state-subsidized childcare centers were less likely to repeat a year of school than those in family day care or with relatives or babysitters.

Studies also show that enrollment in high-quality early-childhood education programs before the age of 5—a critical period for brain development—affects the lives of children years later. A 2017 meta-analysis led by researchers at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, which looked at studies conducted from 1960 to 2016, found that children who participated in such programs were less likely to be placed in special-education classes or to be held back a grade, and more likely to graduate from high school.

“Building the children’s potential is about building the country’s potential,” says Betsey Stevenson, professor of economics and public policy at the University of Michigan. “People usually take low unemployment and rising wages as a time to start families,” she says, but that’s not happening. She believes today’s childcare crisis will have effects for decades. “There’s an entire generation of people that are putting off, perhaps forever, having children because they can’t manage to figure out how it would work.” The data supports Stevenson, with one exception. In 2017, families with incomes of less than $10,000 had higher birth rates than all others. In the long run, this could cause a fundamental economic shift, or as Stevenson puts it: “Basically, the middle-class babies won’t get born.”

Deveau, the mother in Boston, says she and her husband won’t even talk about having a second child before her daughter is in preschool. “It drives me bananas when people say, ‘If you can’t afford to have a child, don’t have it,’” she says. “I can afford to have a child, I just can’t afford to pay for their care for the first three years of their life. That shouldn’t be the benchmark for whether or not you should have children.”

Conservative and liberal economists agree that an effective solution must come from some form of government investment in childcare, as well as better paid-parental-leave policies so people can afford to look after their own children for at least the first few months.

The Trump Administration is currently hosting a series of roundtables with parents, childcare providers and state regulators to explore the challenges that childcare businesses face. This will culminate with a White House summit in November to discuss possible action. “We’re working with governors to see if there are policies in place that limit the supply [of childcare providers] without actually benefiting the quality,” says Ivanka Trump.

On the other side of the aisle, Senator Warren set a standard among Democratic presidential candidates when she unveiled a proposal for a wealth tax on incomes above $50 million, the revenue from which would be used to fund universal childcare. Her plan, which would cost $70 billion per year, would ensure free childcare for families earning less than 200% of the federal poverty line and would cap childcare costs at 7% of household income for all other families.

As Democratic presidential candidates have cycled through Iowa in recent months, talking more about childcare and paid family leave than in recent election cycles, VanderGaast sees an opening. The Iowa day-care director, who also sits on the Cedar County Democratic Committee, has tried to make her case to them directly. She invited Jill Biden to her day-care center during a scheduled visit to Tipton. She met Warren, Klobuchar and O’Rourke, warning that universal pre-K, alone, would be insufficient for parents and detrimental to day cares like hers.

As she notices more local conversation about day-care deserts and discussions of childcare affordability on presidential-debate stages, she is hopeful things might start to change. Her day care—and several million American families—are depending on it.