Updated 10:06 a.m. E.T. on May 9

Here’s an unsolicited tip for the newly appointed head of the House of Representative’s select committee on Benghazi, Rep. Trey Gowdy of South Carolina: A smoking gun explanation for the Obama Administration’s use of false talking points to describe the September 11, 2012 terrorist attack has already been found. And the culprit is not a White House adviser or State Department bureaucrat. It’s the intelligence community’s reliance on the media.

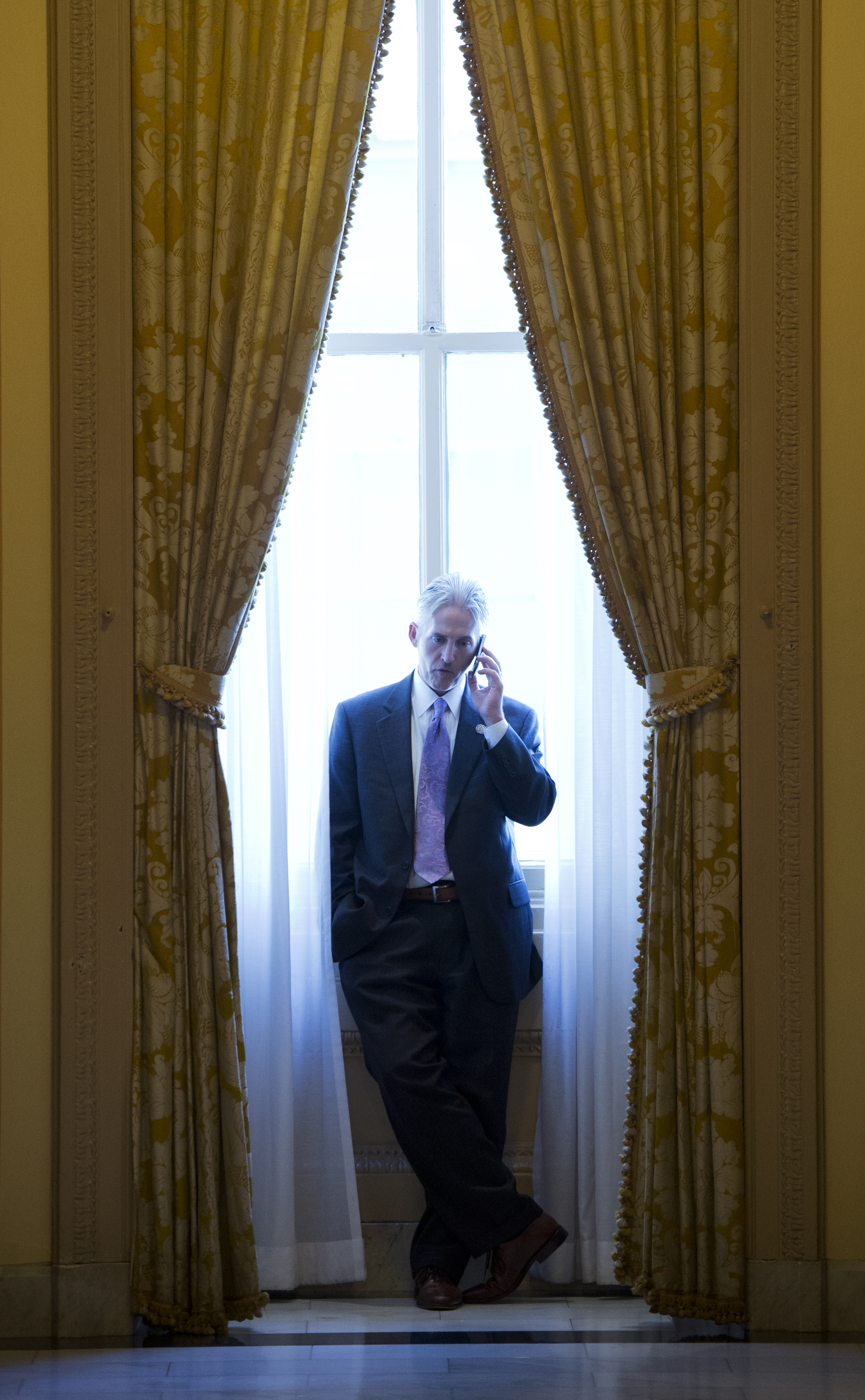

The House voted 232-186 Thursday to set up the select committee on Banghazi, but before Gowdy launches an eight month probe into the attack that killed four Americans, it is worth noting that there is a simple, real-world explanation hiding in plain sight. It’s tucked inside the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence report on Benghazi, which reveals a key source of the bad intelligence that made it into Ambassador Susan Rice’s famous talking points: the media incorrectly reported that before the attack on Sept. 11, 2012 there were protests outside the U.S. facilities in Benghazi when there weren’t.

And the CIA believed those reports, resulting in talking points that were delivered to Ambassador Susan Rice, who told the nation on several Sunday news programs Sept. 16 that the attacks in Benghazi were “a spontaneous reaction” to protests that had occurred on the same day in Cairo against an anti-Islamic video published in the U.S. “People gathered outside the embassy and then it grew very violent and those with extremist ties joined the fray and came with heavy weapons, which unfortunately are quite common in post-revolutionary Libya and that then spun out of control,” Rice told Fox News Sunday, incorrectly. “We don’t see at this point signs this was a coordinated plan, premeditated attack.”

Think of it as a really bad game of telephone. To draw up those talking points, the CIA relied on at least six early press reports that said the Benghazi attacks grew out of protests against an anti-Muslim film that had appeared on the Internet, according to the SSCI report. The source of the mistake looks clear in retrospect. For starters, violence targeting U.S. diplomatic facilities did take place in Egypt, Yemen and Tunisia in reaction to the video. Protests against the film occurred in over 40 countries around the world. Furthermore, reporters for western news organizations interviewed people at the scene after the attacks in Benghazi who said they were angry about the same film. And Libyan government officials repeated the reports. (A TIME story on Sept. 12 referred to “protests” in Benghazi against the film).

But the reports of spontaneous protests preceding the attacks in Benghazi turned out to be wrong. The attacks were launched by well-armed militants rather than spontaneously emerging from demonstrations. And while the CIA had multiple sources, like signals intercepts, in the immediate aftermath of the attacks, the Senate investigation found the agency “relied heavily on open source press reports.”

The subsequent analyses produced by the CIA and others in the U.S. intelligence community were likewise affected by the initial reporting in the media, the SSCI report finds:

[A]pproximately a dozen [intelligence] reports that included press accounts, public statements by [terrorist group Ansar al-Sharia] members, HUMINT reporting, DOD reporting, and signals intelligence all stated or strongly suggested that a protest occurred outside of the Mission facility just prior to the attacks.

The most famous of these reports formed the basis of talking points provided to members of Congress by the CIA Sept. 15, 2012. They began, “The currently available information suggests that the demonstrations in Benghazi were spontaneously inspired by the protests at the US Embassy in Cairo and evolved into a direct assault against the US diplomatic post and subsequently its annex.”

This was despite the fact that on Sept 15 the CIA’s chief of station in Tripoli sent top CIA officials an e-mail that said the attacks were “not/not an escalation of protests” and that survivors recovering in Germany did not refer to protests in interviews. Last month the CIA’s former deputy director, Michael Morrell, testified in front of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence that it was only after the Libyan government said on Sept. 18 that video footage showed no protests that the CIA concluded they had got it wrong.

This lead to Finding #9 of the SSCI report:

In finished reports after September 11, 2012, intelligence analysts inaccurately referred to the presence of a protest at the Mission facility before the attack based on open source information and limited intelligence, but without sufficient intelligence or eyewitness statements to corroborate that assertion. The IC took too long to correct these erroneous reports, which caused confusion and influenced the public statements of policymakers.

The intelligence community’s inability to collect, analyze and assess the value of information that is not secret has been a dangerous weakness of American spook services for a long time. It’s not just that the CIA is bad at catching errors in public news reports. The agency also has a bad track record at finding and prioritizing accurate information that originates not from highly secret sources but from publicly available ones.

A famous example of the agency’s blindness to facts that aren’t secret came when India tested a nuclear weapon in May 1998, catching American policy makers off-guard even though Indian politicians had publicly said they intended to go nuclear. That blindness has apparently continued in the age of Facebook. In the case of Benghazi, the SSCI reported that the CIA missed open source communications in social media around Benghazi that “could have flagged potential security threats”:

Although the IC relied heavily on open source press reports in the immediate aftermath of the attacks, the IC conducted little analysis of open source extremist-affiliated social media prior to and immediately after the attacks.

In the short term, that means that even if the Obama White House and the Clinton State Department were as political and self-serving as their most vehement critics believe, they would still have protection against accusations they misrepresented what happened in Benghazi—they can claim, rightly, to have been reacting to the CIA intelligence analysis.

To avoid even more costly intelligence mistakes in the future, the CIA and its sister agencies need to do better at handling open source intelligence. Concludes the SSCI:

The IC should expand its capabilities to conduct analysis of open source information including extremist-affiliated social media particularly in areas where it is hard to develop human intelligence or there has been recent political upheaval. Analysis of extremist-affiliated social media should be more clearly integrated into analytic products, when appropriate.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com