We are, the critics keep telling us, living in something of a Golden Age for television. But it certainly wasn’t always this way.

Watching the tube in 1961, Newton Minow, then chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, saw little more than a procession of “formula comedies about totally unbelievable families, mayhem, violence and cartoons.” TV was, he famously said, “a vast wasteland.”

Minow wasn’t alone. Jerry Mander, the former advertising exec and current anti-TV crusader, was similarly dismayed. In his landmark 1978 book, Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, he wrote: “It was as if the whole nation had gathered at a gigantic three-ring circus. Those who watched the bicycle act believed their experience was different from that of those who watched the gorillas or the flame eater, but everyone was at the circus.”

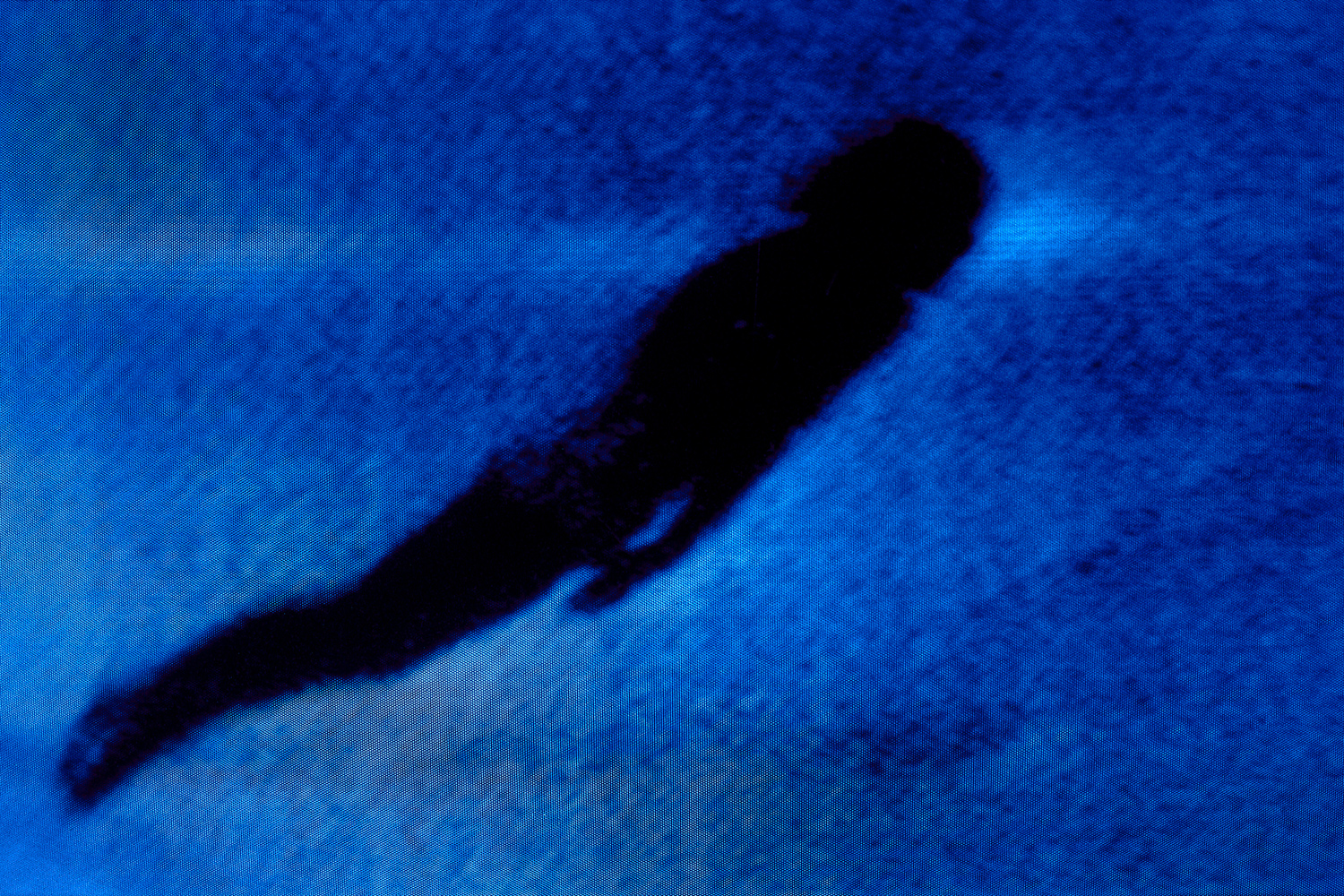

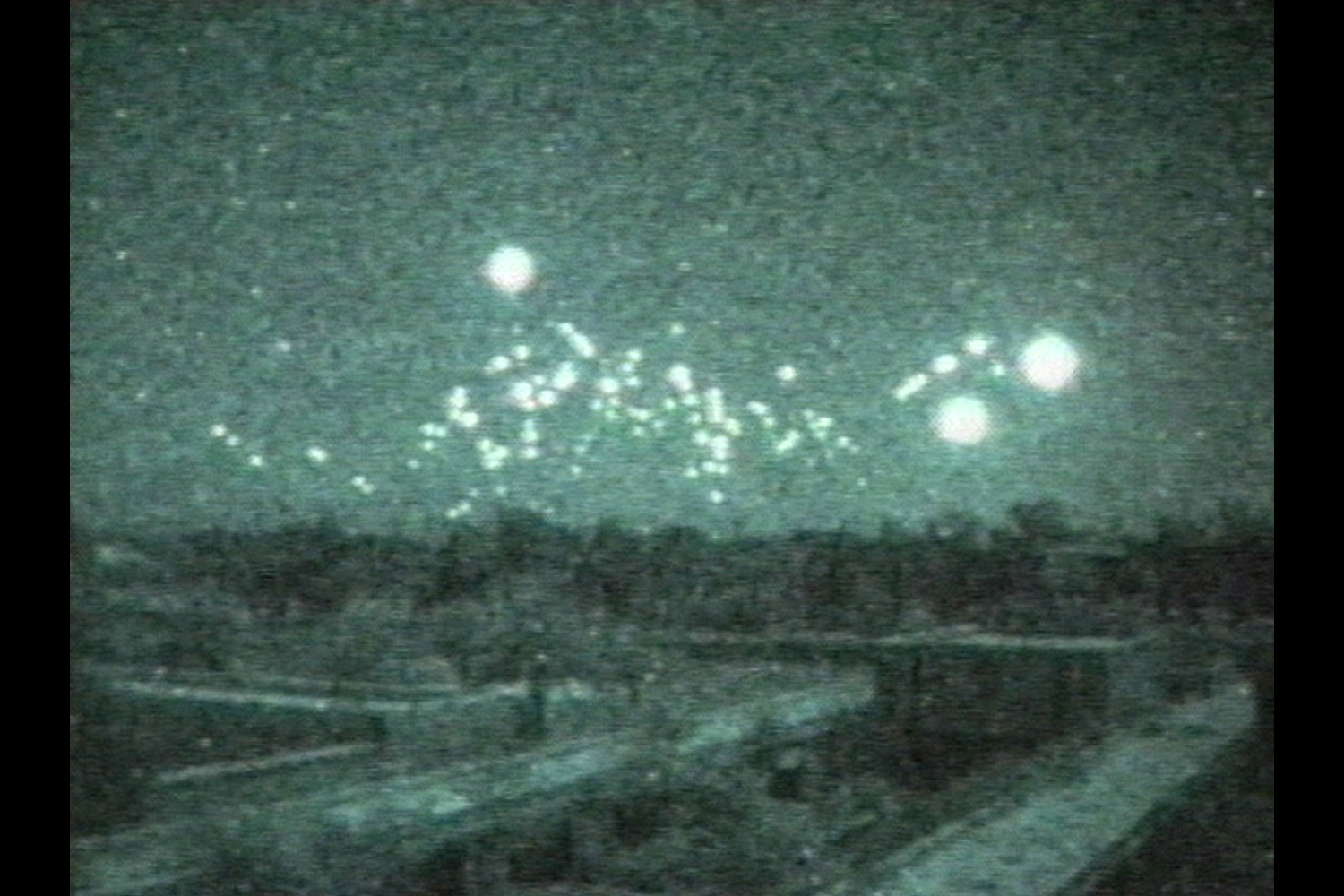

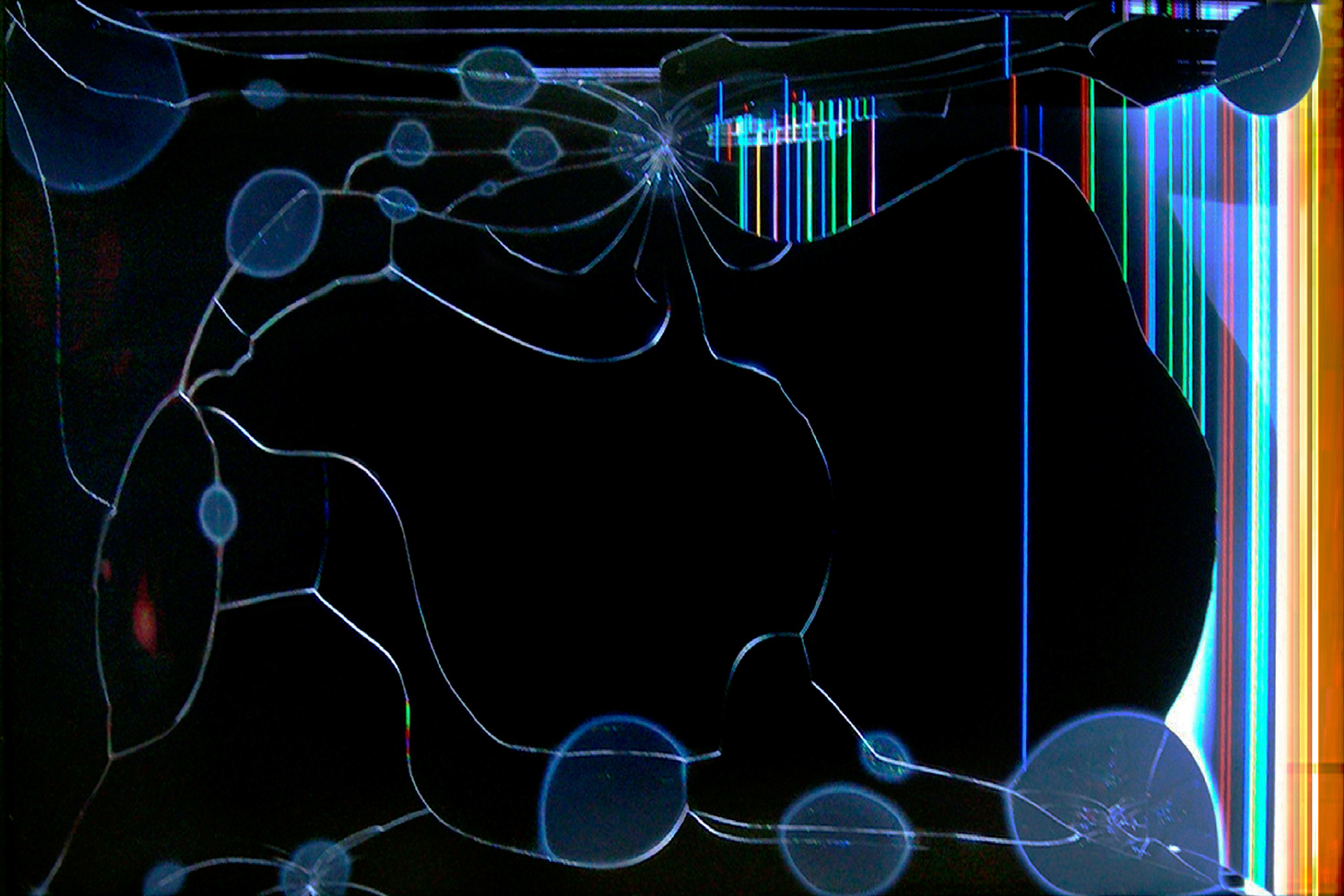

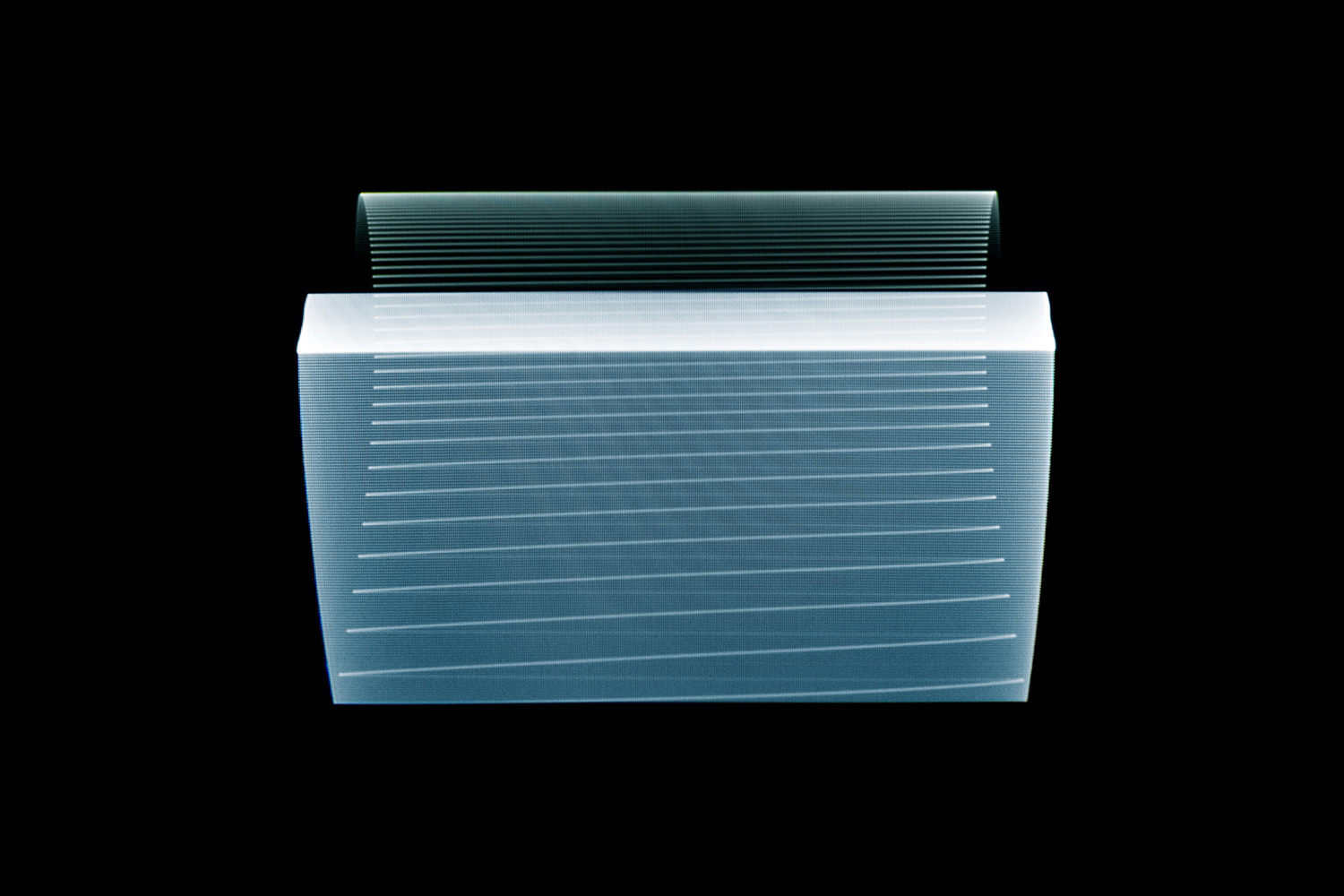

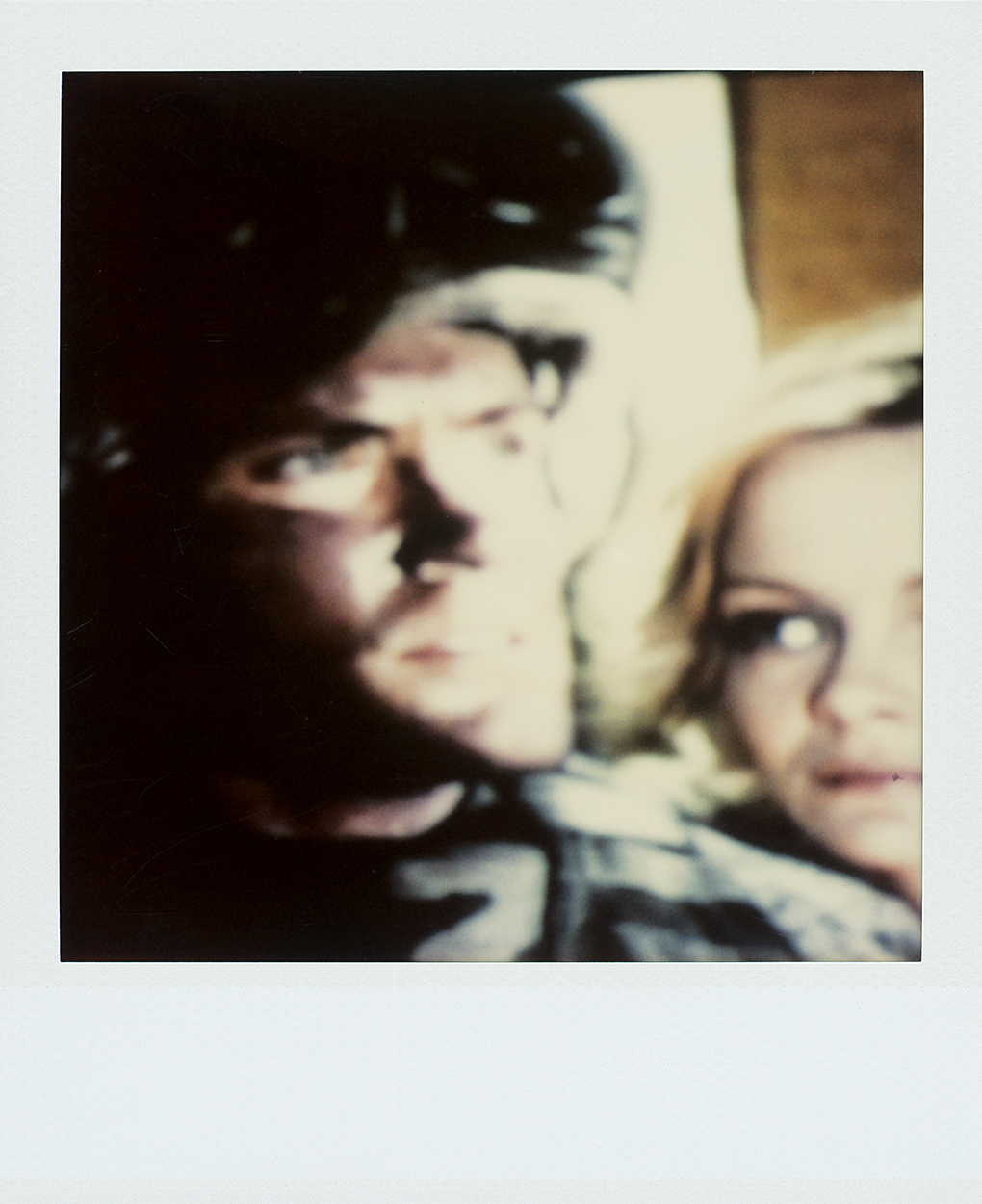

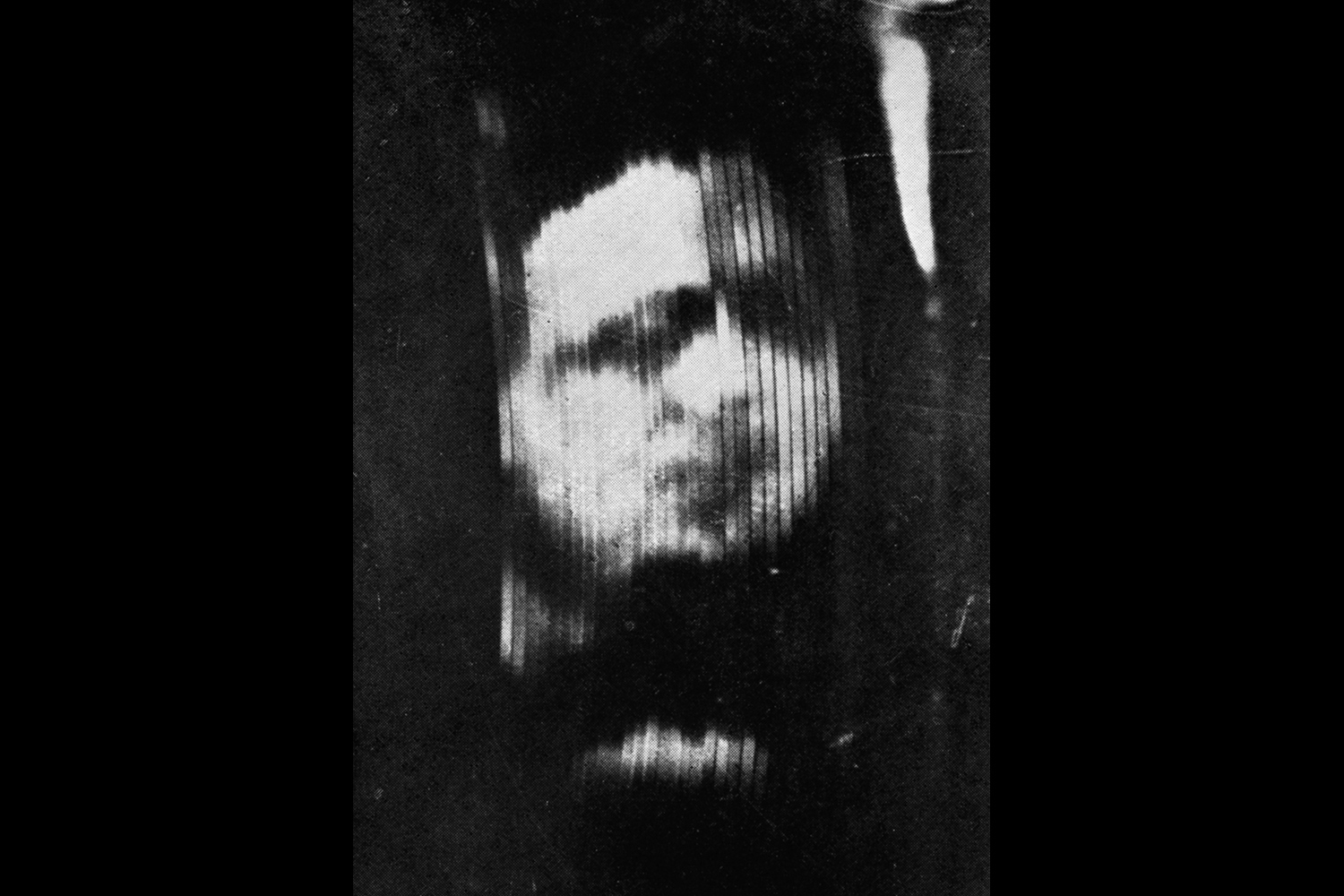

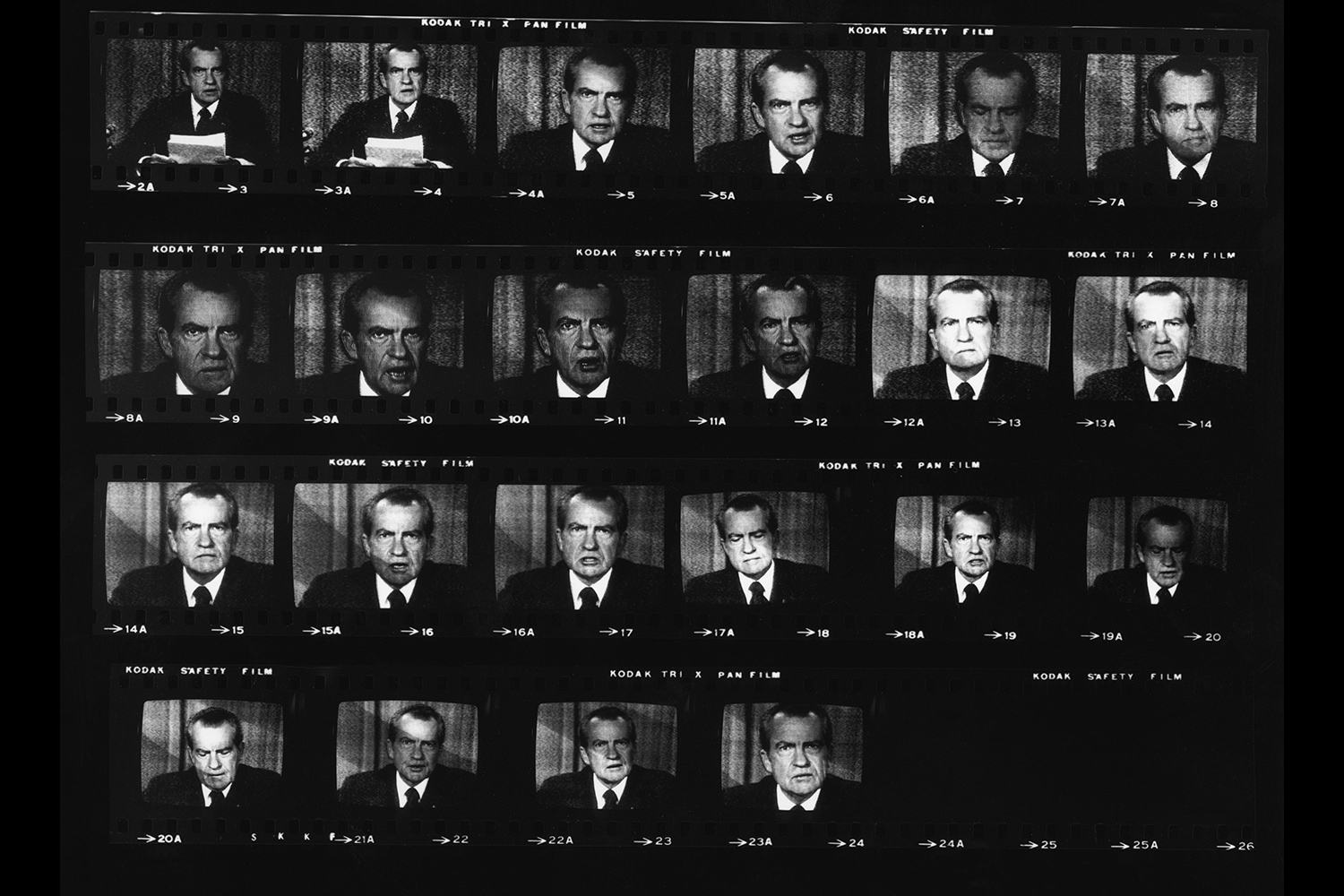

Here, on World Television Day — a UN-sanctioned acknowledgment of the medium’s global reach — LightBox presents images of the tube, from the early years to the present day. The oldest, and perhaps eeriest (slide #9), is a photograph of the first true television ever made, invented in 1925 by John Logie Baird. Images of war, technology and political spectacle were plucked from the wires. Matthew Gamber didn’t use a camera at all—he simply held a piece of photo-sensitive paper against a television screen. Rene Burri shot an entire roll of film on Nixon’s televised resignation (the contact sheet mirroring the sequential nature of TV itself). Penelope Umbrico uses found imagery from the Internet. Stephan Tillmans reveals the striking abstract shapes that zap across old TV screens as they’re turned off. Catherine Opie explores the personal and political through a variety of genres—in this case, Polaroids of icons of power on the nightly news.

Contemporary concerns about TV’s power and influence — just like Minow’s and Mander’s — are, of course, nothing new. Aldous Huxley’s 1931 dystopian classic “Brave New World,” imagined a populace numbed by, and controlled with, popular entertainment, including technology remarkably similar to modern television.

In its Dark Ages, TV was controlled by a handful of networks, each vying to capture as large an audience as possible. Employing stock characters with obvious agendas and clear story lines that wrapped up neatly by the end of each episode, shows routinely appealed to the lowest common denominator.

The advent of cable television changed all that, in effect dicing up audiences according to their narrow interests and sensibilities. Executives realized they could abandon the one-size-fits all approach and make shows that would appeal to many smaller, but far more devoted, audiences. And since cable companies make money from subscriptions, not ads, they could take the kinds of creative risks that would normally scare off advertisers.

Meanwhile, Hollywood’s escalating obsession with blockbusters — and only blockbusters — meant that many talented writers, directors and, especially, actors began flocking to where the work was: television.

Finally, the advent of the DVR, the DVD and subscription services like Netflix allowed viewers to watch and rewatch shows when they wanted—and allowed TV creators to make the kind of nuanced and complex stories that rewarded repeat viewing.

The auteur age of ambitious, challenging TV began with shows like Twin Peaks and Oz, but really took off with daring fare like The Sopranos, The Wire, Lost, Mad Men, Breaking Bad . . . the list goes on

Perhaps most importantly, viewers today have at least a modicum of control over what shows up on television. American Idol allows viewers to vote on its lineup of contestants. Other shows invite their audiences to comment and converse in real time via Twitter and other media. iTunes allows viewers to watch pretty much anything they want to see on the go.

There’s no doubt about it—TV, and our experience of TV, is better than it’s ever been.

But even that invites the question: Are we still, despite everything, at the circus?

Myles Little is an associate photo editor at TIME.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com