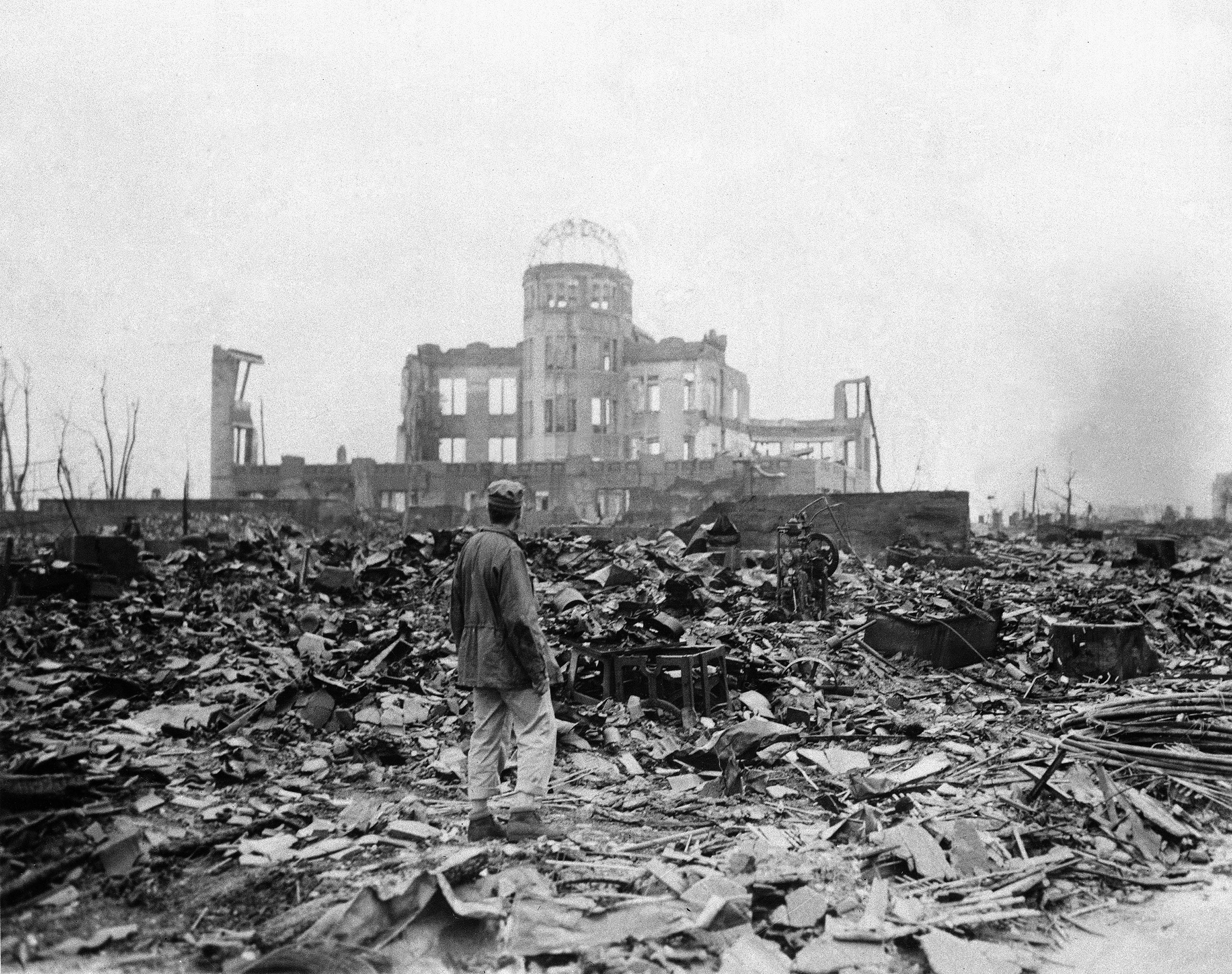

Up until the final days of World War II, the people of Hiroshima thought they were the lucky ones. The U.S. had begun carpet-bombing Japanese cities from March 1945, killing some 100,000 people in Tokyo over just one night. Hiroshima was Japan’s tenth biggest city at the time, yet it had not been targeted by the raids, despite far smaller places already having been obliterated.

“Everyone was wondering, why?“ says Setsuko Thurlow, who was a 13-year-old junior high school student in the city at the time. “Some people thought that Hiroshima produced a lot of immigrants to Hawaii and California, so maybe the U.S. government was grateful. Every day, gossip like that was spreading.”

The truth was revealed at 8:15 a.m. on Aug. 6, 1945. Despite her tender years, Thurlow had been recruited to help decipher intercepted Allied communications and was listening to an army major’s pep talk on the second floor of the wooden building that served as the military headquarters in what today is Hiroshima’s Higashi suburb. Suddenly, she glimpsed a bluish-white flash through the window. It was the atomic bomb “Little Boy,” dropped by the U.S. B-29 Enola Gay, which detonated at a temperature of 7,700°C just over a mile away.

“I had the sensation of flying up and floating in the air,” she tells TIME. “That’s when I lost consciousness.” Thurlow, 91, who in 2017 accepted a Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, was one of only three in her class to crawl out of the debris. “It was a bright summer day, but by the time I came out of the rubble, it was like twilight,” she says. “So we joined this procession of people with parts of their bodies missing, blackened and melted skin; they were not walking, they were simply shuffling.”

The bombings of Hiroshima and, three days later, Nagasaki claimed some 170,000 lives, including nine of Thurlow’s family and 351 of her classmates.

More from TIME

On Friday, leaders of the Group of Seven, a forum of the world’s most developed democracies, come to Hiroshima with the specter of nuclear catastrophe looming larger than any time in recent memory. Russian President Vladimir Putin has repeatedly threatened to unleash nuclear weapons in his faltering war in Ukraine and in March announced he would station tactical nukes in neighboring Belarus. China is undergoing a rigorous modernization of its nuclear arsenal. North Korea, meanwhile, tested a record number of ballistic missiles last year and, experts believe, is also ramping up towards a seventh nuclear test.

In Hiroshima, G7 leaders are expected to make a strong statement condemning any potential nuclear conflict. However, Thurlow and her fellow survivors of the atomic bombings, known locally as hibakusha, believe that words are not enough, urging the grouping to take concrete steps toward ensuring such tragedy doesn’t unfold once again. “Sure, I condemn the behavior of Russia and North Korea,” she says. “But I am not sure the West is showing the willingness to come together and really, in good faith, negotiate for a solution.”

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is no stranger to the arguments. His family hails from Hiroshima, where he still represents its first district as lawmaker, and he also lost several relatives in the bombing. He lobbied to hold the G7 in Hiroshima precisely because of its history. “For 77 years, nuclear weapons have not been used at all,” Kishida told TIME in an exclusive interview late last month at his official residence in Tokyo. “We should not allow the current situation to negate that history.”

However, Kishida has also boosted Japan’s defense budget to 2% of GDP by 2027—mirroring rises across Europe in response to the war in Ukraine—making the officially pacifist nation the world’s third largest military spender. He also agreed to new cooperation with Washington on thwarting potential threats from space, boosting cyber-defense cooperation, reconfiguring U.S. troop deployments on Japan’s province of Okinawa, and developing uninhabited islands for joint military drills. On April 23, Kishida’s Defense Ministry began installing new U.S. Patriot surface-to-air missiles on Sakishima Islands, Japan’s closest territory to Taiwan.

It’s a backdrop that raises the challenge the G7 faces to reduce the risk of nuclear conflict. For one, since Russia was expelled from the G8 in 2014 following its annexation of Crimea, the group is seen as a Western construct of dwindling relevance. The G7’s share of global GDP has dropped continuously, and the BRICS grouping of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa contributes more growth today. With Russia and China firmly convinced that Western countries are intent to contain them, and adroitly convincing the Global South of that fact, the G7’s leadership credentials are suspect.

This is compounded by perceived hypocrisy. For while Russia’s Feb. 21 suspension of the New START nuclear arms reduction treaty—first signed between Washington and Moscow in 2010—is lamentable, the U.S. had already made several destabilizing moves that left global arms control architecture crumbling. In 2001, the Bush administration withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, a cornerstone of Cold War de-escalation mechanisms that limited homeland missile defenses. In 2019, the U.S. nixed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or INF, which eliminated a whole category of nuclear weapons. A year later, it withdrew from the Open Skies agreement, which made all imagery collected from overflights available to any party state. Then, of course, Trump shredded the Iran nuclear deal, which dented U.S. credibility around the world regarding sticking to agreements from one administration to the next.

In addition, all three nuclear weapons states in the G7—plus the whole of NATO and all nations that fall under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, including Japan—have refused to sign the 2017 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) that called for an outright international ban on nuclear use, development, or expansion and a staged disarmament by current nuclear powers. In response to the accord’s adoption at the U.N., the U.S., U.K., and France issued a strident statement condemning it as disregarding “the realities of the international security environment” and “incompatible with the policy of nuclear deterrence.”

It’s actions like this that authoritarian states like Russia and China use to push the narrative across the developing world that the West are equal belligerents in Ukraine, says Ramesh Thakur, professor emeritus and director of the Centre for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament in the Crawford School of the Australian National University. Regarding the TPNW, he believes the nuclear weapons states should end their open hostility to the treaty, especially given all are members of the precursor Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, which hugely overlaps. “Their hardline position has not worked,” he says. “It has solidified the divide and increased the disquiet and suspicion with many countries around the world.”

There are concrete steps the G7 can take to reverse the creep toward nuclear catastrophe. Other than emphasizing U.S. willingness to renew New START, the G7 could go bolder—unilaterally committing to a “no first use” protocol. Already, India and China have adopted this position. While Biden has previously supported the idea, he omitted it from his administration’s latest nuclear policy review, mainly due to pressure from allies that rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella, especially Japan and South Korea, who feel their strategic position would be weakened.

To gain G7 support for “no first use” would take a determined diplomatic effort, though in many ways it is the ideal forum with Kishida in prime place to take the lead. The hope would be that Russia and North Korea would be pressured to reciprocate, or at least it would demonstrate to the wider world the West’s commitment to deescalation. “Strategically, ‘first use’ has never made much sense,” says Thakur. “It’s more as a political-cum-psychological reassurance to allies.”

Certainly, members of the dwindling numbers of Hiroshima survivors—some 118,000 today, according to government records—will be meeting with G7 leaders to tell their stories and encourage action. They will be powerful.

After she emerged from the charred timber, Thurlow and other survivors were directed towards an army training ground around the size of two football fields packed with the injured and dying. “Nobody was speaking, they just didn’t have that kind of physical and psychological strength,” she says. “Some fell down and never stood up again.”

At the training ground, “everybody was just begging for water in faint voices, nobody was screaming loudly,” she says. Although her clothes were covered with blood, she and her fellow surviving classmates were remarkably unscathed, and so set about tending to the dying and injured. “But we didn’t have any cups or any containers to carry the water,” she says. “So we three girls went to the nearby stream and washed off the blood from our bodies and our clothes. We took off our blouses and put them in the stream and soaked them with water.”

The young trio then dashed back to the dying with these wet rags and put them over their gasping mouths, so they could desperately suck out the moisture. “I think we repeated that almost all day, I don’t know how many hours, I didn’t have any sense of time that day,” says Thurlow. “That was the level of so-called rescue operations we could offer.”

Thurlow says that G7 leaders have many more tools at their disposal to prevent such a tragedy unfolding again. They just have to use them. “The way world leaders have been working, if they’re really working, seems to be using humanity as hostage,” she says. “I don’t like it and billions of people don’t like it. We need to feel secure and more comfortable. This is hell we’re living each day.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com