Political conflicts in Washington often seem to resemble a bad sequel to a movie—the kind that recycles the same plot and stars the same actors. The ongoing debt ceiling fight is no exception.

Both political parties have engaged in legislative battles over the debt ceiling since the 1950s, each using it to paint the other as financially irresponsible for supporting a higher limit, only to reach an agreement before markets began to panic. Experts involved in previous debt limit fights expect this one will play out similarly.

At the heart of the political standoff is how much money the U.S. government can borrow to pay for spending that policymakers in both parties have already approved. Congressional Republicans are insisting on cutting non-defense discretionary spending before agreeing to increase the debt ceiling, while President Joe Biden wants to raise the limit without any conditions to prevent a possible economic crisis. “This is without question going to be a more difficult fight to overcome than previous years,” says former Senate Budget Committee Chairman Kent Conrad, a Democrat from North Dakota, who played a large role in the debt-reduction plan during Barack Obama’s presidency.

What’s different this year, compared to the debt ceiling standoffs decades ago, is the intensified political brinkmanship that has taken over Congress, bringing the nation close to default multiple times in recent years and resulting in the U.S.’ credit rating being downgraded for the first time in 2011. It’s not yet clear whether this year’s standoff will be as worrisome. Biden has so far refused to negotiate with Republicans, a risky bet that is likely rooted in his experience with debt ceiling fights. In 2011, when Biden served as Vice President, his party gave in to major spending cuts after they opened bipartisan talks. But when Democrats refused to engage from the beginning in 2013, House Republicans acquiesced in the end.

“The thinking by Democrats has been that if we just hold out and don’t negotiate, we’ll win,” says Bill Hoagland, a longtime director of the Senate Budget Committee and a former financial policy advisor to Republican Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist. “That’s hardball, and I don’t think President Biden really wants to do that.” Strategists and policy experts in both parties believe Democrats will at some point have to come to the bargaining table to negotiate a debt ceiling deal.

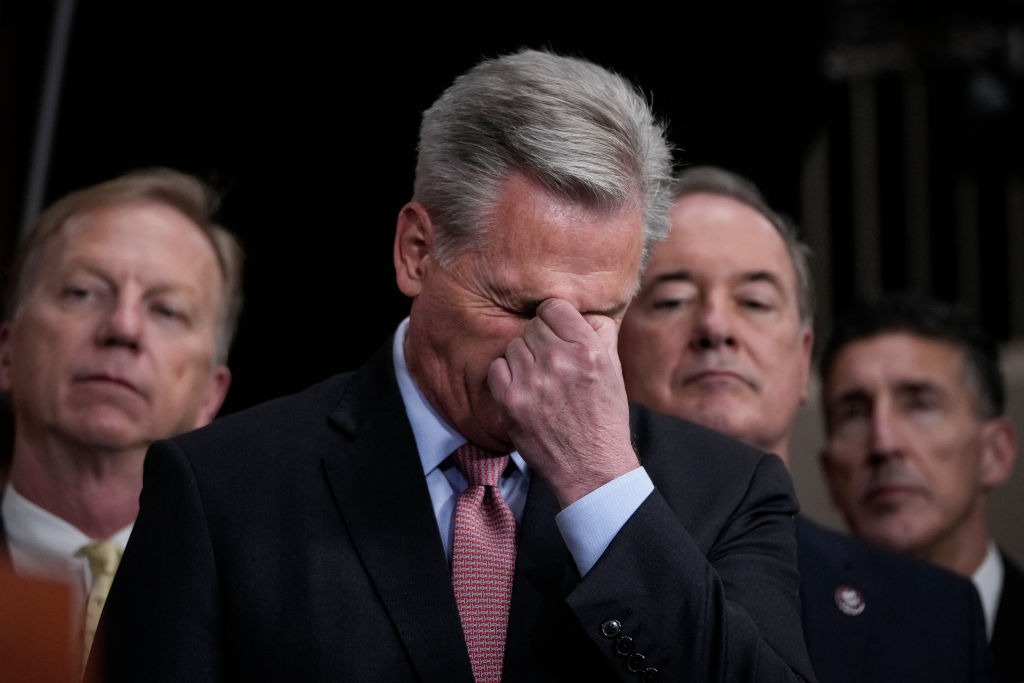

The U.S. officially hit the debt ceiling last month, and as a result could face the prospect of default as soon as June if lawmakers and the White House do not strike a deal to raise the federal borrowing limit. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy on Wednesday unveiled a plan to raise the debt ceiling into next year, outlining a proposal for his conference that includes repealing the Inflation Reduction Act, returning the federal government spending to fiscal year 2022 levels, and limiting spending increases over the next 10 years to 1% of annual growth. McCarthy’s plan would also claw back unspent COVID-19 aid and require Americans to work to receive certain federal benefits. In total, he estimates that the plan will save the government $4.5 trillion over the next decade. But its path to passage is complicated.

A number of House Republicans have already voiced their opposition to raising the debt limit under all circumstances, and McCarthy can only afford to lose four votes. Some of the Republicans who have expressed their disagreement with the notion of an unconditional debt limit hike argue Biden must agree to certain spending cuts in exchange for their votes on the debt ceiling. Some of the cuts they seek include scrapping nearly $400 billion to boost clean energy and combat pollution in the Inflation Reduction Act, and an end to Biden’s student debt cancellation measure. Some Republicans have also targeted the roughly $80 billion recently approved to help the IRS pursue corporations and high-income earners that underpay taxes, though that move could add to the deficit since it may prevent the government from collecting money it is owed.

The uncertainty over the path forward for Republicans suggests that McCarthy may need support from some Democrats to pass the debt ceiling increase. But his willingness to seek Democratic votes could also hurt his already-weak standing in the GOP. “There’s a rhythm to these standoffs,” says Jim Kessler, a former legislative director for Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer before he became Majority Leader, who is now the executive vice president for policy at the center-left think tank Third Way. “At a certain point, the adults get in a room and there’s movement. But we haven’t reached that point yet.” Kessler adds: “McCarthy is in the toughest position because his caucus is really not together.”

On Wednesday, the bipartisan House Problem Solvers Caucus released a separate proposal for avoiding a default on U.S. debt if the White House and congressional leadership fail to reach an agreement. The plan would suspend the debt ceiling for six months and establish an independent fiscal commission—modeled after a Pentagon panel that determines which military bases to close—to determine ways to reduce the debt.

Experts say not to expect a miraculous deal any time soon. “It’s going to look like we’re on the verge of disaster for quite a long time,” Kessler says. But he predicts the government will eventually avoid default: “I’m an optimist because I’ve seen this movie, and at least three of the four starring actors have played this role before. It’s not a great movie, but it’s a movie.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Nik Popli at nik.popli@time.com