The fate of an Army sergeant Daniel Perry, who was found guilty of fatally shooting a protester at a Black Lives Matter demonstration in 2020, is up in the air as the Texas pardon board reviews the conviction for a possible pardon at the governor’s request and Perry’s attorney pushes for a retrial.

On April 7th, Perry, a 35-year-old active duty sergeant at Fort Hood, was convicted of murder in connection with the death of Garrett Foster, 27, who was killed after Perry shot him during a protest in Austin, Texas, in July 2020. Perry claims he acted in self-defense because he feared for his life after Foster, who was carrying an assault rifle under Florida’s open carry law, allegedly made him feel threatened.

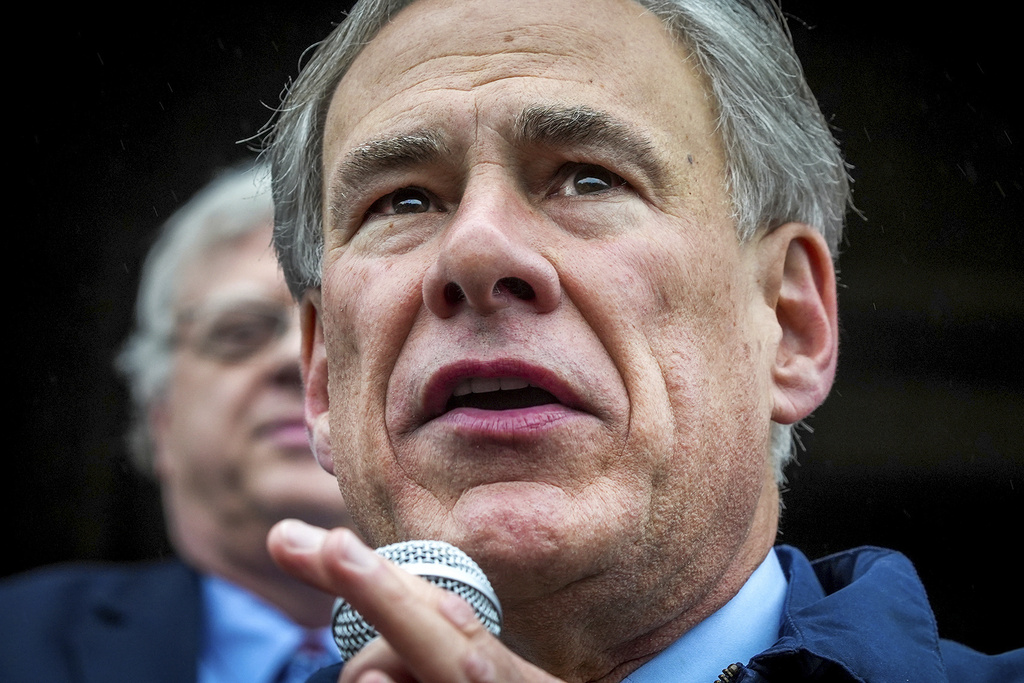

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott believes that Perry should be exonerated based on Texas’ stand your ground law, which allows using deadly force to defend yourself if you feel you’re in danger.

Abbott called for an expedited review of Perry’s conviction on Saturday. “I am working as swiftly as Texas law allows regarding the pardon of Sgt. Perry,” Abbott tweeted. “I look forward to approving the Board’s pardon recommendation as soon as it hits my desk.”

More from TIME

Travis County District Attorney José Garza said in a statement that Abbott’s attempted intervention in the case is “deeply troubling.”

“As this process continues, the Travis County District Attorney’s Office will continue to fight to uphold the rule of law and to hold accountable people who commit acts of gun violence in our community,” Garza said.

Here’s what we know about the case.

What is the case about?

The conflict between Perry and Foster took place during a protest on July 25, 2020 in Austin, Texas—two months after the death of George Floyd. Perry was driving for Uber and was legally carrying a handgun in his car, which his attorney, Clint Broden, said he had for protection. Perry came upon the Black Lives Matter protest and encountered Foster who was also legally carrying an assault rifle. But accounts of what happened next differ.

According to Perry’s attorneys, Perry made a turn onto Congress Avenue and protesters began to bang on his car. Perry claims he was not aware a protest was happening at the time, and that Foster approached him and “motioned with the assault rifle for Mr. Perry to lower his window.” Perry obliged, and later fired at Foster with a handgun five times before driving off, resulting in Foster’s death. Perry’s attorneys said that Foster was acting out of self-defense because Foster raised his assault rifle towards Perry.

At least three witnesses, however, testified in late March that Foster was holding his rifle down when he approached Perry’s car, according to the Austin American-Statesman. (One of the witnesses first said that she could not remember where the barrel of Foster’s rifle was pointing, though she later changed her mind and said it was not pointed at Perry. During an interview with the Austin Police Department, Perry seemed to contradict his own defense argument when he said, “I believe he was going to aim at me. I didn’t want to give him a chance to aim at me.”

Critics have also questioned Perry’s intentions after online users identified a tweet he sent out in response to then President Donald Trump’s post ahead of his Tulsa, Oklahoma rally in 2020 about “protestors, anarchists, agitators, looters or lowlifes…,” saying they would not be subject to the same treatment as demonstrators in New York or Seattle. “Send them to Texas we will show them why we say don’t mess with Texas,” Perry tweeted in response, per the Texas Tribune. Perry’s attorney told the Tribune that “anyone who thinks he went to Austin with an agenda” was wrong and was taking Perry’s posts out of context.

In July 2021, Perry was indicted on murder charges, and was convicted of murder on April 7. A jury found Perry not guilty of an additional aggravated assault with a deadly weapon charge. He has not yet been sentenced.

In the meantime, Perry’s lawyers filed for a retrial on Tuesday, saying that they were not allowed to display evidence that they claim shows Foster instigating confrontations the night before he was killed.

What are Texas’ rules for pardoning?

While Abbott supports overruling the jury and pardoning Perry, he does not have sole power to do so—unlike the President of the United States. He does, however, still have a lot of say in the matter.

The Texas constitution says the governor may only issue a pardon if the state’s seven-member Board of Pardons and Paroles recommends it. All the members of the board were appointed by Abbott.

Jennifer E. Laurin, a law professor at the University of Texas School of Law, tells TIME that it’s possible Perry may serve no time if a pardon is granted.

“The implications of a pardon here depend on the timing of it. Perry has not yet been sentenced so if a pardon happens tomorrow [before the sentencing], it would mean that you would never serve a sentence,” Laurin says. “If it were to happen after he began his sentence, it would mean that he wouldn’t have to serve any more of it.”

Laurin adds that it is also possible that Perry could receive a partial form of clemency that would reduce his sentence.

District Attorney Garza has since written to the chair of the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles asking for the opportunity to present evidence before they make a decision. “In addition, I ask that you request to hear from the family of the victim, Garrett Foster, before you make your final recommendation,” he wrote.

Laurin notes there is no clear deadline for the Board’s decision to be issued, and that when a decision is made, the Board does not need to file a reasoning for their choice.

“The Board of Pardons and Paroles, and the governor ultimately can face a clemency determination, on many factors that have nothing to do with sort of discrete questions on legal correctness in the judgment,” says Laurin. “A pardon is a determination that notwithstanding a finding of guilt, that individual deserves mercy for one reason or another, perhaps evidence of reformation over time, or perhaps evidence that the purposes of punishment are no longer sort of given the advanced age of the individual.”

However, because of the early timing of the request for a pardon, Laurin says that the basis for a pardon would have to be related to concerns about the way the trial was conducted.

What are ‘stand your ground’ laws?

Supporters of Perry suggest that he acted in self-defense, and should thus be exonerated from culpability. There are different types of self-defense laws across the United States. The “castle doctrine,” for instance, protects individuals’ right to use force, even deadly force, to protect themselves against intruders in their home.

Florida expanded on this concept in 2005 when it passed the country’s first “stand your ground” law, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. That law legalizes self-defense outside of a person’s home, saying that a person does not have a “duty to retreat” from an attacker and can meet “force with force.”

At least 28 states, including Texas have laws that say there is no duty to retreat from an attacker. Other states have laws that require a person to retreat before they use deadly force as a form of defense.

However, Laurin notes, Texas law also says that a person cannot use deadly force in defense of themselves, if they “provoked the use of deadly force that they are responding to.”

This fact played a substantial role in the case against Perry. Witnesses testified that Perry looked to be driving into the crowd of protestors intentionally, according to the Tribune, which would make him culpable for the aggression he says he faced.

“The state’s contention was that he deliberately drove into the protesters the victim was part of because he had a desire to essentially make trouble and use force against that group,” Laurin says. “While it is true that Texas has a strong stand your ground law, there are provisions of Texas law on self defense that were at issue in this trial that provide a plausible legal basis for understanding why the jury rejected the assertion of self defense here.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com