April 8, 2023 marks half a century since the death of the world’s most famous painter, Pablo Picasso. “My mother said to me,” he once revealed, “‘if you are a soldier, you’ll become a general, if you are a monk, you’ll become the pope.’ Instead, I was a painter and became Picasso.”

Just one word: Picasso. More than fifty exhibitions in over twenty countries will be celebrating this artist like no other. Last September, the Spanish and French Ministers of Culture launched an entire year of celebrations with typical pomp and ceremony. And yet, for the first four decades of his life in France, Picasso was treated with wariness, suspicion, and even scorn by the same country that now acclaims him as one of its great geniuses.

In 1900, a young, brash Picasso arrived in Paris from Barcelona to make his name as an artist, joining the luminous center of the art world. But he did not roll down the Champs Élysées. He entered the city through the narrow doorway that was Montmartre, a neighborhood of subalterns, bohemians, and foreigners, and he was quickly labeled an anarchist by the police—equivalent to being called a “suspected terrorist” today.

In a France shaken by waves of xenophobia, obsessed by the idea of “national purity,” and corseted by the omnipotence of its Academy of Fine Arts, Picasso endured the triple stigma of being a foreigner, a purported anarchist, and an avant-garde artist, before the latter became a badge of honor. He mingled with non-conformists, free thinkers, poets, and other expatriates who understood and supported his art. From the Russian Empire to the United States, from Munich to Prague and from Berlin to Vienna, he became a sensation, and a wealthy man.

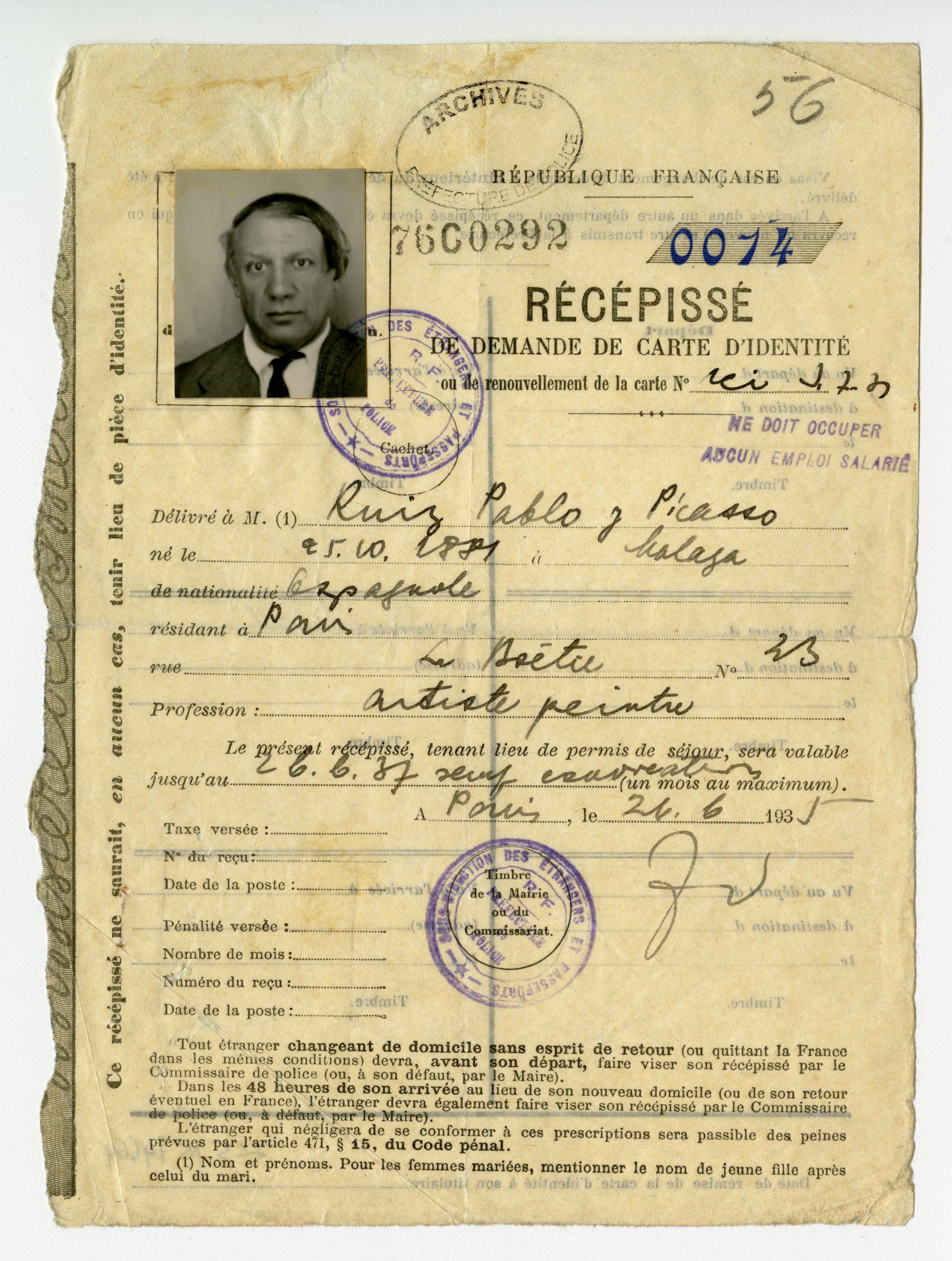

In Paris, however, he remained a foreigner and an individual who regularly aroused the attention of the authorities—all while enduring the political instability of the 20th century, with the Spanish Civil War, two world wars, and a Cold War taking place in the heart of a Europe torn apart by nationalism.

Nevertheless, by the 1930s Picasso was perceived as a singular talent outside of France, especially in the U.S., where Alfred Barr, the director of MoMA celebrated him as “so fecund and versatile a genius” that no retrospective “can lay claims to completeness [. . .] even with more than 300 works.” When Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), his cubist masterpiece, joined MoMA’s permanent collection, Barr went a step further, declaring, “There are few works of art in which the arrogance of genius presents itself with such power.”

In 1937, when the civilian population was annihilated by fascist bombings in a small Basque town, Picasso seized the moment to produce, in a matter of weeks, his iconic masterpiece Guernica, widely considered the most famous work of art of modern times. “The Old World has committed suicide,” Picasso’s friend, writer and anthropologist Michel Leiris, commented. Meanwhile, Guernica traveled to museums throughout the Western world and raised money for the Spanish Republicans. Picasso became the leading anti-fascist artist of the period.

And yet both stability and formal recognition in France eluded him. In Paris, fearing for his life at a time when fascism was on the rise all over Europe, Picasso decided to apply for French citizenship—a request which was rejected by the police. This rejection could have broken him, but it did not; rather, he continued to work and reinvent himself. He became the “general” that his mother saw in him, and continued to push the boundaries of modern art.

That he was able to do so is no coincidence. Picasso’s status as an as outsider in France meant that relied on his inventiveness and nonconformity for inspiration and survival. Could a creature of the establishment have painted Guernica? Picasso became Picasso because of his foreignness.

It was only after World War II, having finally been contacted by the director of France’s museum of modern art, that Picasso made a generous donation of ten paintings to the French state. All of his conflicting feelings about France accumulated over the previous decades are summed up in this gesture: the pariah transformed into a patron of the arts, the ignored, the excluded artist now a great tutelary figure.

But even as the French establishment grudgingly accepted him, he turned his back on Paris. In 1955, he left for the South of France, never to return. He became a ceramist and made ceramics into a high art. This late-career burst of creativity not only reaffirmed his genius, but also aligned him with local artists and craftsmen. He chose the South over the North, the artisans over the Academy of Fine Arts, the provinces over Paris, and tied his international fame to the sphere he had always belonged to—the Mediterranean, rich with its plurality of cultures.

In an age when xenophobia is on the rise, let’s remember that Picasso was himself a foreigner, subject to prejudices that might remind us of those endured by people crossing the Mediterranean, the English Channel, and the Rio Grande today. He came to France for his own unique reasons, but the hostility he faced remains sadly familiar.Today more than ever, Picasso’s odyssey, his endless strategies to overcome adversity, are a model that all of us must urgently reflect upon.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com