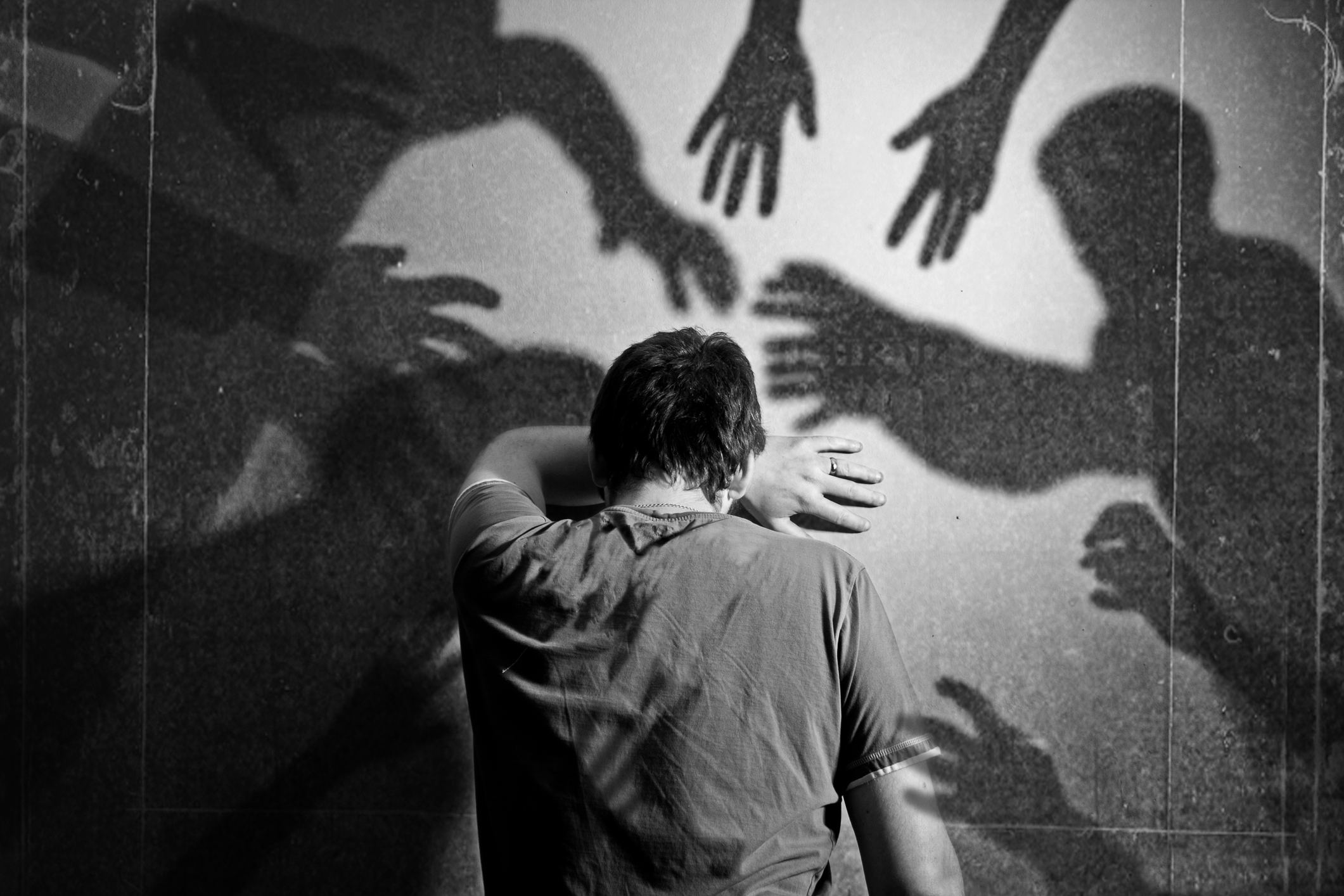

Many of us have had this uncanny feeling before: Entering a silent room, walking through a dark night, or waking from sleep—and suddenly, it’s there. A sense that someone is with us, without any sight or sound. A feeling of a presence.

It’s a sensation that occupied the forefathers of psychology for a long time, including William James. Writing in the Varieties of Religious Experience, James wrote of “a feeling of objective presence, a perception of what we may call ‘something there,’ more deep and more general than any of the special and particular ‘senses.’” It was an experience he recognized as key to many a spiritual occurrence, but also one with an often sinister and foreboding air. A friend of James’ recounted a night-time encounter of his own that he experienced as a student: “I did not recognize it by any ordinary sense and yet there was a horribly unpleasant ‘sensation’ connected with it. It stirred something more at the roots of my being than any ordinary perception.”

If you’ve had this experience and you’ve tried to explain it to someone, you may be met with a blank look, or even skepticism. It sounds like something out of a ghost story, and indeed, William James was a kind of 19th-century ghostbuster. He was a key member of the Society of Psychical Research, which was set up to examine the truth behind telepathy, spiritualism, and apparitions of the night.

But what we now know is that James’s friend was correct. This isn’t a ghost story, or even a sixth sense, but something at the roots of our being. Contemporary neurology, cognitive neuroscience, and psychiatry shows us that such presences truly belong to us because they are linked to how our bodies and minds give us a sense of self.

Read More: Why Sleep Paralysis Makes You See Ghosts

The first piece of evidence comes from case studies of people affected by epilepsy, brain tumors, and other major changes to brain functioning. For instance, in a 2006 study, a 41-year-old man, whom the study called “PH,” presented to a hospital clinic complaining of fatigue, dizziness, and seizures. The one night in hospital, he awoke to feel he had split into three parts: his left side, which felt normal; his right side, which felt somehow detached; and then off to his right, another man who wasn’t him. This figure mirrored his body position, and when he tried to look at him, he looked away; PH felt as if “they shared the same soul.” Beyond the man stood a woman, again mirroring PH, and beyond that, some girls; he called them his “family.” After a few days the image of these figures receded, but the feeling of their presence remained.

PH’s experiences were the product of an aggressive tumor in the left hemisphere of his brain, which affected two areas in particular: the posterior insula and the temporoparietal junction. The former is a key brain area for processing internal information about our bodies (like heart rate or gut feelings), while the latter is involved in integrating our senses to make a map of where we are in space. Damage to those areas would have changed PH’s internal model for where he felt his body was. So when he was visited by this presence, in a way it did share his soul. It was where he should have been (or his brain thought he was).

More from TIME

The next piece of evidence comes from cognitive neuroscience, and a team led by neurologist Olaf Blanke in Geneva. Since 2014, they have used a robot to induce feelings of presence in healthy individuals and clinical disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease. The robot works to disrupt your sensory expectations: Whenever we make a movement, our brains are thought to make a set of predictions about what will happen to our senses. Go to clap your hands, and your brain is ready for a new sight and sound, all at the right time. But if you mess with that, strange things start to happen; things don’t feel like “us” and instead start to feel like they belong to someone else. With the presence robot, you make random pressing movements into the air in front of you, while the robot presses you in the back at exactly the same time. In sync, it almost feels like it’s you pressing your own back—you brain takes the cues from your own movements, and the sensations on your back, and comes to the conclusion that the only person in this process is you. But when the touches start to then go out of sync—slowing and dragging, not quite hitting where they should—participants suddenly feel like a person, not just a robot, is controlling the touches from behind. Lots of people with Parkinson’s have feelings of presence as part of the condition, and this makes them particularly susceptible to the phantom touches of the robot.

Lastly, we’re now beginning to recognize that feelings of presence are a missing piece in the story of psychosis. Not long after William James was writing, figures like Karl Jaspers were describing examples of presence in some of the first textbooks of psychiatry. But the trail ran cold for a number of years—until very recently. There’s now evidence that people who hear voices (or have auditory hallucinations) also describe high rates of felt presence—literally voices than can be there without speaking. And grassroots work such as Rethink Psychosis, led by people with experience of psychosis themselves, are calling for more recognition and understanding of the phenomenon through projects like “Psychosis Outside the Box,” a collection of the more neglected and unusual aspects of psychosis.

The strangeness of presences makes them all too easy to miss in a time-pressured doctor’s appointment, but for many people, it may be the figure behind voices or visions that matters the most. If you’ve ever had your own personal space violated, or dreaded to go into certain places because of who might be there, you will know how much the presence of another can affect you, even without a word being uttered. Thinking about presences, and not just voices, poses a whole new set of challenges for our scientific models of psychosis and how we deliver psychotherapy. It’s even part of some of the newer psychotherapeutic approaches to psychosis, such as AVATAR therapy.

The through-line in all these examples is the self. In Western societies, we are used to the idea of a unitary, consistent self—the core of us that never changes. But psychologists and neuroscientists know that the self is something that can be disrupted in multiple ways; it’s less of a one-man band, and more of an ensemble piece. In clinical disorders, case reports, or through ingenious experiments, we can observe how radically the self can altered to produce a presence.

It goes beyond that, too. Given the right conditions, all of us could have this is experience, whether as a result of grief, exhaustion, trauma, or even sleep problems. In this way, the new science of presence isn’t about a mysterious “other,” after all. It’s a way of learning about ourselves.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com