The latest episode of the hit mockumentary sitcom Abbott Elementary—created by and starring Quinta Brunson—tackles a question that has loomed over its second season: Will the underfunded public school where Brunson’s Janine Teagues loves to work become a charter school? This plot has sparked much debate and discussion online and among real life teachers about the charter school movement. Critics of charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately operated, argue that they skirt accountability and regulations and attempt to make public education private. Proponents say charter schools can offer increased opportunities to students, given that they do often access more funding.

On Abbott, the teachers and parents whose children attend the titular school teamed up to make a change. Facing the news that Draemond (Leslie Odom Jr.)—an Abbott alum and now owner of the Legendary Schools charter network, which in turn owns the nearby Addington Elementary—is trying to take their over their school next, they unite to make sure Abbott stays public. The episode resolves (for now) one of the overarching storylines of the season, which has, over a handful of episodes, carefully illustrated the detrimental effects of charter schools on existing public schools and students.

Earlier in the season, viewers speculated online that the show was indirectly referencing Jeff Yass, reportedly the richest man in Pennsylvania, who has put millions of dollars into support for charter schools. At one point, seasoned older teacher Barbara Howard (Sheryl Lee Ralph) questioned whether charter schools take “private money from wealthy donors with ulterior motives.” On March 7, Jeanne Allen, the director of Yass’ education foundation, told the Philadelphia Inquirer that the line was a “gratuitous slap against people with wealth.” Following Wednesday’s episode, Allen tweeted, “The creator, lead writer and co-producer of @AbbottElemABC @quintabrunson is from West Philly and attended charter schools her entire education. She reportedly loved it at the time, heaped praise on it. Once upon a time. Guess money talks.”

Brunson responded, “you’re wrong and bad at research. I only attended a charter for high school. My public elementary school was transitioned to charter over a decade after I left. I did love my high school. That school is now defunct—which happens to charters often.”

“Loving something doesn’t mean it can’t be critiqued,” she continued. “Thanks for watching the show :)”

The show’s creator has long been an advocate for public education, but has been careful with her wording. Speaking with TIME last month, she said that we should be giving just as much support to public schools as we do to charter schools. “Are charter schools better? Maybe,” she said. “But can we support our public schools more so that we don’t feel like one is necessarily better than the other? Because public schools have so much to offer. And we wanted to focus on: How can we support our public schools?”

For teachers around the U.S., charter schools are a constant concern, beyond an episode of television. They find relief, both comic and real, in Abbott—as well as tangible education and information.

“There’s this myth that charter schools provide more opportunity or their graduation rates are better, but that’s just because they exclude kids,” says Brooklyn public school teacher Frank Marino, who formerly worked at a charter school. Watching Abbott “felt so cathartic, because I was like, yes, it was a public platform where those myths are being busted by parents.”

How Abbott Elementary addresses charter schools

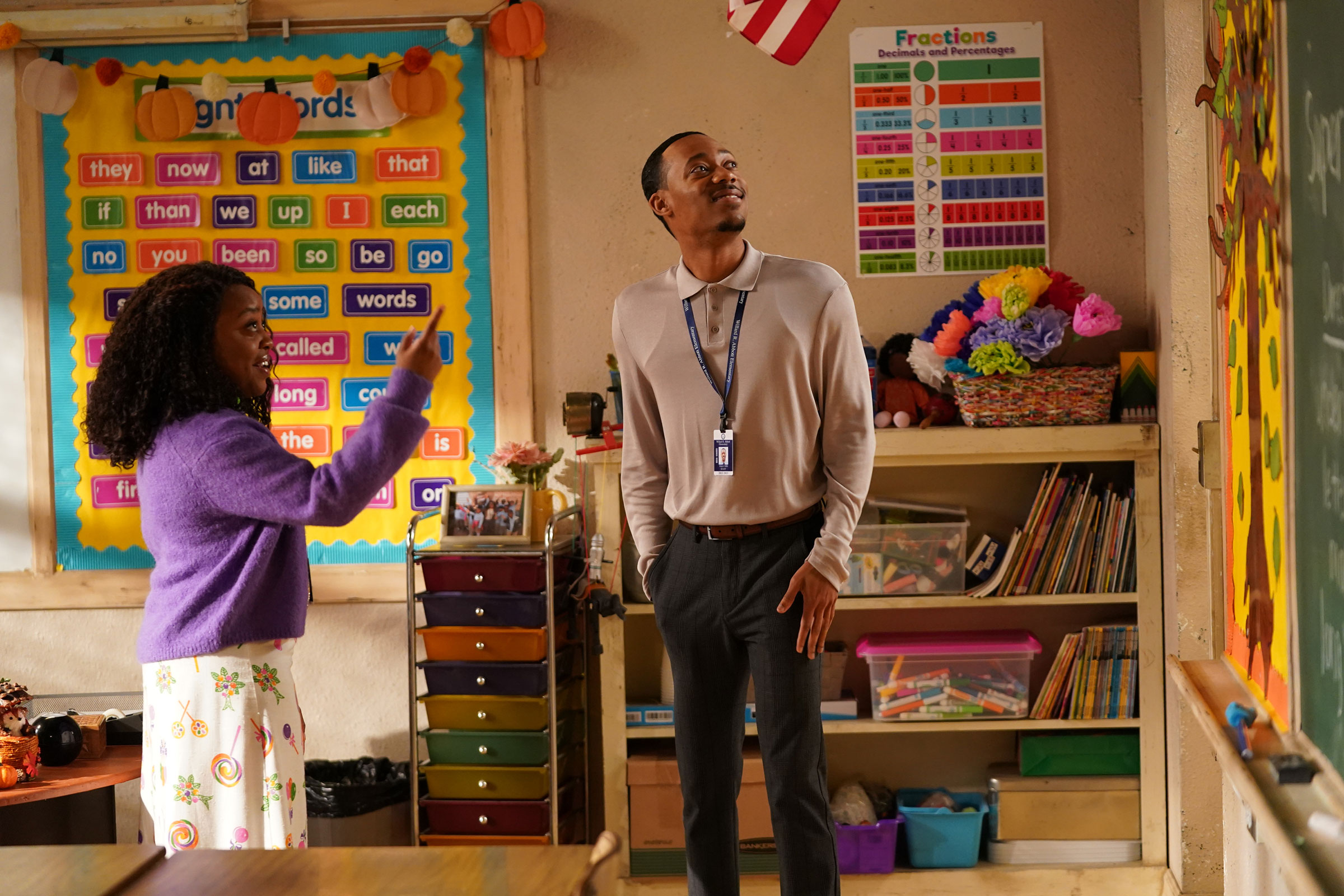

In this week’s episode, Abbott is hosting Ava Fest—ostensibly not named after Principal Ava Coleman (Janelle James)—to collect signatures from the community in support of staying public. There’s a dunk tank, step dance routines, somehow soupy and solid macaroni and cheese—and then there’s Draemond. The charter school magnate upstages the evening’s entertainment—aspiring rapper Tariq (Zack Fox)—appealing to the parents of Abbott Elementary. Abbott, he says, is holding their kids back. Addington and Legendary Schools offer a better, fresher alternative. But Abbott’s parents aren’t quite convinced.

“My kid went to Addington, and you kicked him out,” says one outraged mom.

“No, we don’t—we don’t kick kids out,” Draemond says. “We encourage a small few to explore other educational opportunities.”

Slowly, but surely, the parents challenge and debunk his claims. Draemond says Legendary Schools will hire the best and brightest teachers. “What about the teachers we have here now?” counters a mom. A dad discovers that his kid, who already attends Abbott, might not get to continue at the same school because Legendary Schools would implement a lottery system.

“Hold on, hold on, hold on, I play the lottery every single day, and I never win,” Tariq interjects. “This man is playing the Powerball with our kids!”

The crowd jeers, laughing Draemond out of the room.

Teachers commend Abbott Elementary‘s charter school storyline

Abbott Elementary has brought Kathryn Vaughn, an art teacher at a public school in Tennessee, and her husband back to appointment viewing TV like it’s the ‘90s. Vaughn loves the show, but says she was surprised to see it tackle charter schools, a $49.5 billion industry with heavy political sway. She appreciated how the most recent episode hands the power to the parents.

“You want to be like the smart parents,” Vaughn says. “You don’t want to fall for all the glitter and glam and clean tile floors of the charter school. You’re more than that, parents, right? You’re deeper.”

In many states, public schools are mandated to have arts education in each building, and tenure in the arts for someone like Vaughn is possible. Charter schools, however, have more leeway: Some, like Addington Elementary in Abbott, can choose to bring in an art teacher a couple of days a week, often subcontracted out from a company.

“Charter schools make me incredibly uneasy,” Vaughn says. “They don’t have to offer their employees tenure. They don’t have to hire certified staff to teach. So if you’re sending your child to a charter school expecting a great arts education, you might not even be taught by certified staff.”

Abbott Elementary is set in West Philadelphia and Vaughn’s school is in western Tennessee, but no matter where you are in public education right now, she says, you know: the push for privatization is huge.

“That’s really the big connection between urban poor and rural poor, like I’m in, is the funding,” Vaughn says. “Urban schools almost are a little sexier. They get more of the money than us in the rural, poor areas. But we’re all behind where we should be with funding.”

A few episodes ago, at the fictional Pennsylvania Educational Conference for the South East Area (PECSA), Jacob (Chris Perfetti)—a well-meaning history teacher—is hanging out with a group of teachers from Addington Elementary. One of them, Summer (Carolyn Gilroy), tries to convince him to switch schools, telling him, “We’re all about focusing on the kids who have the best chance of making it out.”

“Out?” Jacob asks. “Out of what?”

The scene hit home for Marjahn Finlayson, a climate change educator, researcher, and activist who previously worked at a charter high school in Hartford, Connecticut. While teachers there often took a personal interest in their work, she says, there was little trust in the community.

“In the PECSA conference episode, Addington teachers are talking to Jacob about, like, ‘Oh, we take the best kids, and we try to get them out of the ‘hood,’” Finlayson says. “And Jacob is like, ‘Why are you taking them out?’ That was how the feeling was for me.”

Finlayson noticed disparities in resources between public and charter schools, regardless of the quality and dedication of teachers.

“That’s why it’s easier for these schools like Legendary Schools to get into an inner city space, like where Abbott is, where Hartford is,” she says. “It’s easy to prey on these communities that have a need, based on the fact that public school funding isn’t going to this space, but it’s going to another.”

One of Abbott’s arguments against charter schools is that, as Barbara grimly puts it, “They don’t see students. They see scores.” At Finlayson’s former charter high school, one student was repeatedly pressured into applying to college, despite wanting to pursue a trade career.

“And it wasn’t even the fact that she needed to go, it was just that she had to apply,” Finlayson says. “Because, ‘We have a 100% college acceptance rate, and we’re not going to mess with that number.’”

Earlier in Abbott’s second season, an upset mother bursts into the school and asks the principal if her son can re-enroll—he was just kicked out of Addington. Incredulous, she reads aloud the letter Addington sent her: “We regret to inform you that Joshua Richardson no longer reaches the standards required for our educational nourishment.”

“That’s just BS-speak for he brought down their test scores,” says second-grade teacher Melissa Schemmenti (Lisa Ann Walter). Between this scene and Ava Fest, Marino tells TIME he felt like the show understood him. The episode, he says, is accurate in the way it represents “the lack of certification or expertise that those students will be getting in a lot of these networks, and the ways that charter schools that are these big networks will funnel resources into marketing to create this perception that they’re better, they’re newer, they’re shinier. And inherently putting public schools as this second tier or lower tier experience while hiding these large charter school networks’ role in creating those conditions.”

One Abbott episode is dedicated entirely to an “attack ad”: a commercial run by Draemond that slanders Abbott Elementary and offers Legendary Schools as a solution. For all of its well-produced patina, though, all the ad does, as Barbara puts it, is hurt teachers like her.

Perhaps the polar opposite of that attack ad comes at Ava Fest, when teachers banded together to save their school, and parents pulled through to support them.

“Mostly what I saw in the episode was we are the union,” says Marino, who is also a chapter delegate for the United Federation of Teachers. “It’s not this organization that’s outside of us. Whenever we act collectively, we will win.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com