In fourth grade, I remember seeing Maya Angelou on my television for the first time. Angelou was a fierce advocate for the LGBTQIA+ community at a time when few people were, once famously reciting, “I am gay. I am lesbian. I am Black. I am white. I am Native American. I am Christian. I am Jew. I am Muslim” to a crowd of queer people in Florida in 1996. While she wasn’t a part of the queer community, I recall feeling a sense of kinship towards her. The feeling of hearing her powerful voice reciting her poem “And Still I Rise” with the image of thousands of Black students participating in a graduation ceremony had a profound impact on me and my ability to see myself as not only one of those graduates, but also someone who could one day contribute to and celebrate the rich history of Black people.

Growing up and exploring my identity further, I never once saw a Black LGBTQIA+ person like me represented in my history books. As a matter of fact, I rarely learned about Black historical figures outside of the common heavy hitters such as Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Sojourner Truth, or Harriet Tubman. While they are monumentally important to our history as Black Americans, they also represent very specific factions of our struggle for justice and liberation.

When I first discovered Angelou, I immediately started reading as much of her work as I could—albeit with a dictionary on hand—and learned how fortitude is often born from our most painful periods. It wasn’t until much later, in graduate school, that I was introduced to the works of LGBTQIA+ authors for the very first time—writers like Audre Lorde and bell hooks. Their radically inspiring approach to Black queerness and feminist theory resonated with me on a much deeper level: How, as Lorde once wrote, “caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare;” how the struggles to end racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia are inextricably intertwined. Reading their words instilled a sense of pride in me, particularly as someone who wrote more than I spoke. These collective experiences throughout my life made me want to continue learning and pursue a career in research, so I could help expand public knowledge on important topics impacting people like me.

As the Director of Research Science at The Trevor Project, my work focuses on adolescent gender and sexuality, and reducing LGBTQIA+ youth mental health disparities. My research particularly looks at the role that protective factors—such as supportive and affirming schools or LGBTQIA+ role models and representation—have on reducing this risk. Every student should experience moments of feeling seen and represented in school. When we see ourselves reflected in books or in the media, it opens up a world of possibilities that we may have never known were otherwise possible and inspires a new generation of thought-leaders.

Unfortunately, politicians are attempting to strip that hope by censoring curriculums and banning books related to both Black and LGBTQIA+ topics. In 2023 alone, more than 400 anti-LGBTQIA+ bills have been introduced across the country—most of which target transgender and nonbinary young people—with more popping up each day. We know that LGBTQIA+ young people are listening as their rights are being debated on the national stage. For LGBTQIA+ youth of color, these types of bills can have a compounding negative impact on their mental health and well-being—they force not just one aspect, but multiple aspects, of their identities into the shadows. Nearly 7 in 10 Black LGBTQIA+ youth say debates around state laws restricting the rights of LGBTQIA+ young people have negatively impacted their mental health, and 1 in 5 also reported experiencing cyberbullying or online harassment as a result of these policies and debates in the last year.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in Florida. In March 2022, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis signed what became commonly known as the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, banning classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity from kindergarten to third grade or “in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” The very next month, he signed the originally-named Stop the Wrongs to Our Kids and Employees (WOKE) Act, which prohibits classroom instruction or diversity training in workplaces that imply a person is privileged or oppressed based on their identity.

“Don’t Say Gay” has had a chilling effect, discouraging teachers at all grade levels from ever discussing the LGBTQIA+ community, offering supportive resources, or displaying symbols of Pride in their classrooms out of fear of retribution. In fact, one bill has been introduced that would extend the ban on LGBTQIA+ related classroom instruction through ninth grade, and prohibit students and teachers from respecting pronouns or personal titles that don’t correspond with one’s sex assigned at birth through twelfth grade. In a similar unwarranted effort to “protect” students, the state of Florida decided in February 2023 to reject the College Board’s new AP African American Studies course on the grounds that it “lacks educational value” and equates to “indoctrination.” Particularly, the Florida Department of Education took issue with the course including lessons on intersectionality and Black queer studies. It’s clear that Florida officials view public education on marginalized identities and ongoing cycles of oppression as threats to their power and their ability to perpetuate these cycles.

This type of extreme government overreach and censorship comes at a time when new CDC data found suicide rates significantly increased among Black young people between 2018 and 2021. Among Black LGBTQIA+ youth, The Trevor Project’s research found that 19% reported attempting suicide in the past year compared to 12% of their white LGBTQIA+ peers. And when broken down by gender identity, our latest study shows that 1 in 4 Black transgender and nonbinary youth reported a suicide attempt in the past year—more than double the rate of suicide attempts compared to Black cisgender young members of the queer community. This staggering data further emphasizes the importance of applying an intersectional lens to understand the world around us and the disparities that exist across our most marginalized and vulnerable communities.

My Blackness is everything to me—it shapes how I perceive the world and how the world perceives me. But as a queer nonbinary Black person that holds multiple marginalized identities, the stakes are even higher for me. I am hyper-conscious of how I present myself in predominantly white spaces and often feel misunderstood or invalidated in heteronormative spaces. It’s a nuanced balancing act that I have to perform every day, and is a direct result of my intersecting identities. To reject the concept of intersectionality is denying my own lived experiences, and that of so many other Black LGBTQIA+ people who have to navigate a world that so often causes them harm.

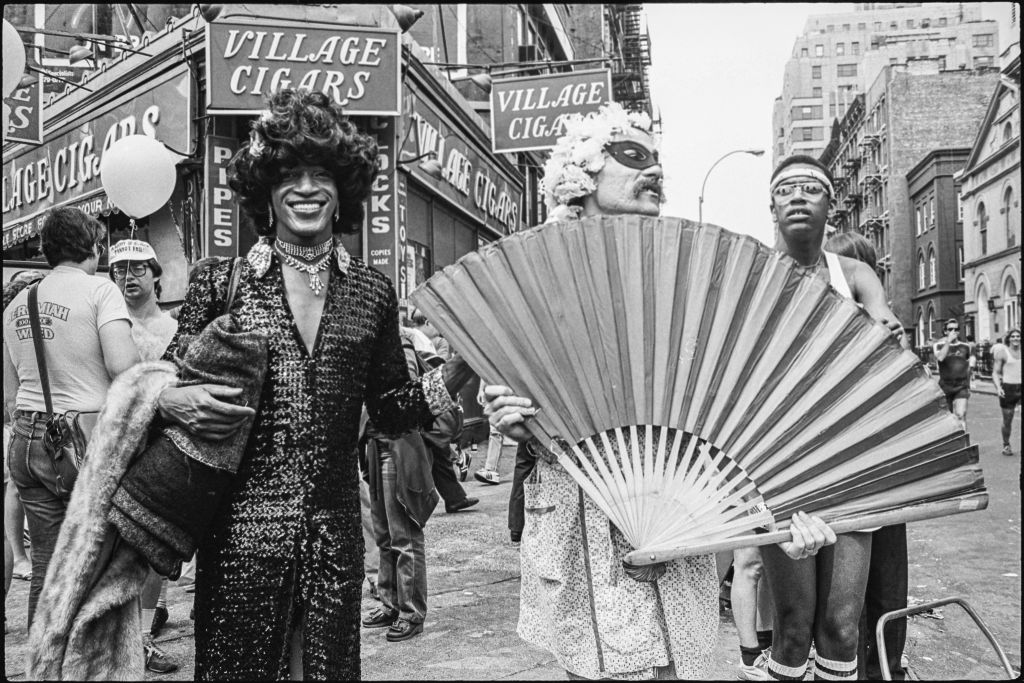

Black LGBTQIA+ history is complex, rich, and, yes, traumatic. It’s the harsh reality of not only our nation’s dark past, but the current state of society. Attempting to censor classrooms from teaching about the contributions of Black LGBTQIA+ people will erase critical decades of history—from Bayard Rustin’s leadership in the Civil Rights Movement and Marsha P. Johnson’s role in the Stonewall Riots, to the timeless literary works of James Baldwin. Innovative writers such as Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Alain Locke and entertainers Ethel Waters, Bessie Smith, and Ma Rainey defined the Harlem Renaissance and paved the way for Beyoncé’s Renaissance. In the words of African American literary critic Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Harlem Renaissance “was surely as gay as it was Black.”

Fast forward to today, and we have press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre, the first Black woman and openly LGBTQIA+ person to hold the position, and activists such as Black Lives Matter co-founder Patrisse Cullors inspiring a new generation of Black LGBTQIA+ leaders. Black, queer history is American history, and it has shaped nearly every aspect of our culture as we know it today.

Students shouldn’t have to wait until they potentially find themselves in a college classroom to learn about people with a shared identity. Black history, which is already primarily limited to our experiences in enslavement and segregation, must stress that Black people are not a monolith in order to fully embody the diversity that is the Black experience in America. While our shared experiences around racism and systemic oppression bond us, our myriad of identities cannot simply be packaged into a one-stop-shop curriculum. LGBTQIA+ students—like all students—deserve to have their history and experiences reflected in their education.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com