For residents of southeast Paris, the construction vehicles rumbling back and forth behind the Austerlitz train station are a loud annoyance that has gone on for too many months. But for city officials—and countless Parisians, they hope—history is unfolding behind the cordoned-off area. After years of thwarted ambitions and vague promises, the French capital, officials say, is set to accomplish a rare feat for a major metropolis: making its once heavily polluted waterway fit for swimming again.

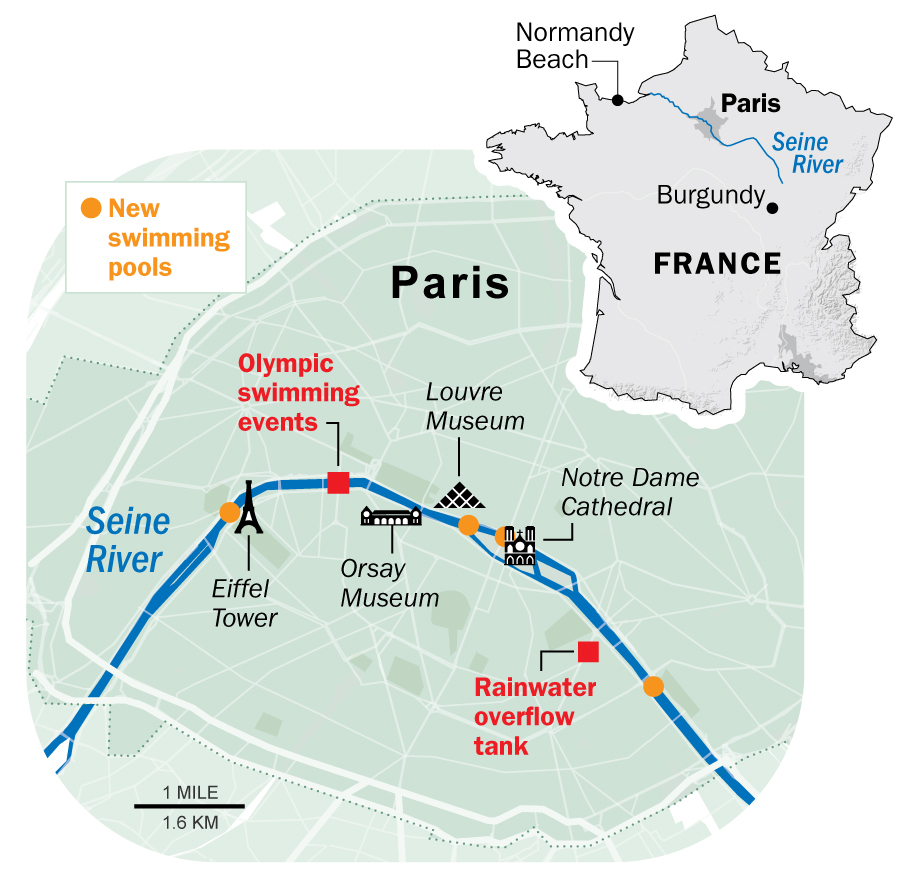

In February, city officials invited TIME to pass through the metal turnstile behind the cordon, and see up close the cleanup of the Seine—one of the world’s most iconic rivers—which stretches for 481 miles, from Burgundy through Paris out to the sea in Normandy. Indeed, the river has defined Paris since it was founded by ancient Romans. It was along these riverbanks that merchants in the Middle Ages first set up, creating a settlement that finally dwarfed once bigger rivals like Lyon and Marseilles. And it was on the banks, too, that the world’s finest architects constructed the Eiffel Tower, the Notre Dame Cathedral, and the Louvre and Orsay museums—stunning monuments that draw millions of visitors each year to sail down the narrow stretch of the Seine that cuts through the dead center of Paris. Officials are therefore keenly aware of the deeper significance of cleaning up the Seine, seeing it as a way of connecting the modern city to its oldest history. “The Seine,” says Emmanuel Grégoire, deputy mayor of Paris in charge of urban planning, “is the reason why Paris was born.”

Once the €1.4 billion ($1.5 billion) project is finished—by next spring, if all goes to plan—Parisians will be legally allowed to swim in the river for the first time in a century. (Authorities banned it in 1923 because of high levels of pollution.) “Swimming at the foot of the Eiffel Tower will be very romantic,” Grégoire says, before guiding TIME underground into the giant—and decidedly unromantic—rainwater storage tank, crucial to cleaning the Seine.

In recent years, smaller European cities, like Zurich, Munich, and Copenhagen, have opened urban swimming. There are also efforts under way to make swimming possible in Berlin’s Spree River and Amsterdam’s canals, with frequent meetings among cities to discuss what is required. Yet Grégoire is keen to point out that making the Seine swimmable could mean Paris becoming the world’s first giant urban area to have inner-city bathing. “It is a dream,” he says.

Some believe the Seine’s cleanup will also spur similar projects elsewhere. “The Seine River is maybe the most romanticized river in history, in literature,” says Dan Angelescu, founder of Fluidion, a water-monitoring tech company based in Paris and Los Angeles, which has taken daily readings of pollution levels in both cities’ rivers since 2016. The Seine cleanup, he says, “obviously has a lot of emotional impact on people, and definitely acts as inspiration to others.”

Los Angeles, which will host the 2028 Olympics, has sent water and sanitation officials to Paris to study the Seine cleanup. When asked which other major cities are watching how Paris is cleaning the Seine, Angelescu responds, “I think everybody.”

But for Parisians, setting a global example may matter less than the tangible benefits of making the Seine swimmable again. There are environmental advantages: officials predict the revival of fish stocks that have dwindled over the decades, as well as the restoration of river foliage. A swimmable Seine could also give Parisians an escape from sweltering summer temperatures; Paris hit a record 108.6°F in 2019. Further, an economic motivation looms large: cleaning the Seine was a cornerstone of Paris’ winning bid for the 2024 Olympics, an event that could generate up to €10.7 billion ($11.4 billion) for the French economy and create 250,000 jobs, according to a 2017 study by the Centre for Law and Economics of Sport (CDES) at the University of Limoges in west-central France.

The idea of cleaning up the Seine is hardly new. In 1990, then Paris mayor and later French President Jacques Chirac declared he would launch a major cleanup of the Seine, and swim in it “in three years.” The idea withered over the years, and Chirac died in 2019, his grand ambition unfulfilled.

What makes this time different is the pressing Olympics deadline. When the current mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, presented her winning bid for the 2024 Games back in 2016, she promised that the city, home to 11 million people in the greater urban area, would undergo a drastic environmental upgrade by 2024. Key to her bid was enabling Olympic athletes to swim in the river, as they did when Paris hosted its first Olympics in 1900. “From 2015, we decided we were going to take advantage of the Olympic Games to considerably accelerate the vision,” Grégoire says. “It was a really important part of the candidacy.”

The 10K swimming marathon, the aquatic portion of the triathlon, and one Paralympics swimming event are set to start in the Seine—at a venue built under the ornate 19th century Alexandre III bridge in central Paris. The river will also be used for the marquee opening ceremony: rather than the global norm of using an Olympic stadium, athletes will kick off the Games on a flotilla of boats sailing 6 km (3.7 mi.) through the city—past Paris’ most famous landmarks strung along the Seine. “We need to use its monuments, its culture, its history,” Paris Olympics head Tony Estanguet told TIME in an interview last year, about the significance of centering the Games on the Seine. Some 600,000 spectators are expected on the riverbanks, more than seven times the capacity of France’s biggest stadium in northeast Paris.

A year after the Games end, Parisians will have access to 26 new swimming pools in the Seine, expected to open by 2025, four of them in the city center. The pools will be walled off from heavy boat traffic that carries cargo, garbage, and about 7 million tourists a year.

These changes represent a sharp break from all of Paris soiling its river for centuries. That includes throwing into the Seine the bodies of those killed in the 16th century religious wars between Protestants and Catholics, and in more recent decades discarding TV sets, motorcycles, and other large items in the river; 360 tons of large items are hauled out of the Seine every year, according to the Hauts-de-Seine local government on the western outskirts of Paris. But the biggest source of pollution in modern times has been the dumping of countless tons of wastewater—which includes domestic and industrial sewage—into the river.

Fortunately, the city says that as a result of recent infrastructure upgrades, the amount of untreated wastewater that ended up in the Seine in 2022 was 90% lower than 20 years ago. Despite this progress, pollution is still a problem; last year, 1.9 million cubic meters of untreated wastewater was spewed into the Seine. Dumping all of this into the river, officials say, is necessary to avoid saturating Paris’ sewage network and flooding the city when especially heavy rain hits. But the Seine has paid the price over the years.

Some 150 years ago, Napoleon’s city planner Georges-Eugène Haussmann carried out a massive remake of Paris, putting into place infrastructure that may have been cutting-edge in the 1860s but is now largely antiquated, says Samuel Colin-Canivez, chief engineer for major sanitation works in Paris.

The Haussmann approach, for example, involved a combined sewer system, in which waste and stormwater runoff from the streets are collected in the same network. Since the 1980s, efforts have been made to modernize: spillways have been automated and fitted with valves. That has drastically cut down the amount of untreated wastewater going into the Seine, but has not entirely eliminated the problem.

That combination of older sewage systems and new ones plus pipes carrying everything from drinking water to fiber-optic cables means there is a labyrinth of infrastructure running under Paris’ sidewalks and streets—Colin-Canivez calls it “a little museum.” Figuring out how to divert excess rainwater amid this jumbled mess, so that domestic and industrial sewage is not flooded into the Seine, has been the costly and complicated engineering challenge.

Read More: Paris Buried a River 100 Years Ago. Now The City Needs To Resurface It to Combat Climate Change

The planned solution is centered on building the giant underground rainwater storage tank in southeastern Paris, which lies behind the cordoned-off construction site near the Austerlitz train station. There, a steep spiral staircase gouged into the ground opens into a giant, cavernous hole, walled with cement. When TIME visited in early February, two earthmovers were busily digging deeper and deeper, their lights illuminating the darkness, and their engines drowning out conversation.

The structure is mammoth, equivalent to roughly 20 Olympic-size swimming pools, capable of holding up to 45,000 cu m (more than 10 million gal.) of rainwater. Once completed by next spring, it will measure 50 m (164 ft.) wide and 34 m (111.5 ft.) deep, and have one crucial job: to hold runoff water during a rainstorm, preventing it from overwhelming the city’s sanitation network, and thereby having untreated waste flow into the Seine, as currently happens.

Once the project is completed, a tunnel will link the rainwater tank (or bassin, as the French call it) to the bank directly across, diverting it from the sewage system. From there, it will be released slowly into the sewer network, then treated downstream in Paris’ sewage-treatment plants, before finally passing into the river, all aided by the natural downhill flow.

The obstacles Paris faces in transforming its river are the same in old cities elsewhere, including in America. The U.S. set a goal under the 1972 Clean Water Act to make all rivers and lakes swimmable and fishable by 1983.

Yet 40 years past that deadline, the plan is far from complete, with some blaming outdated monitoring equipment and lax standards. There is a reason that it’s taken so long: most of the world’s largest cities were built long before modern sanitation networks were knit into urban planning. “You cannot put in a whole new sanitation system. It’s ridiculously expensive,” says Robert Traver, a leading urban-river specialist and engineering professor at Villanova University in Philadelphia. That city, for example, has had a plan for years to transform its section of the Delaware River and make it swimmable; much like the Seine in Paris, the river cuts through the city.

But decades of budget cutting and politicking have slowed progress. “We have a 20-year plan, and at the end of the 20 years, we have another 20-year plan,” Traver says. “Whether it is ever going to happen, I don’t know.” Looking over the engineering plans for the Seine with TIME, he says, “Nothing in Paris’ plan is unique. But to do it is unique.”

Yet cleaning the Seine might not be the final challenge for Paris officials. Parisians will need to feel safe enough to swim in the 26 swimming pools along the Seine that will open after the Olympics. Public confidence in the cleanup is not certain, given years of E. coli and enterococci bacteria in the water, and the possibility that a particularly heavy rainfall could contaminate parts of the river.

Last summer, hydrologists measuring fecal bacteria in the Seine at the Olympics’ planned river venue in central Paris found that 90% of samples were already clean enough for swimming, according to city officials. The city is also hopeful that three pools built more recently along the La Villette canal in eastern Paris, which opened for swimming in the summer of 2016, can help build public confidence that the Seine can be safe for dips. Grégoire says the water is tested daily for bacteria. “We manage to have the pools open for swimming 95% of the time,” he says.

Still, when the polling agency Ifop asked 1,000 French people in 2021 what they thought of the Seine, 70% described it negatively, with some calling it dirty, polluted, and smelly.

For now, city officials are not deterred. They believe their plan will only build on the progress made in recent years to upgrade waste treatment—and make the Seine swimmable nearly all of the time. “Our goal, really a philosophy, is that we have to stop polluting. It’s a major global issue,” Grégoire says. “By making the Seine swimmable, that is the best of the best examples.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com