Bernie Sanders is here to answer a question nobody in this room was asking: Is it okay to be angry about capitalism?

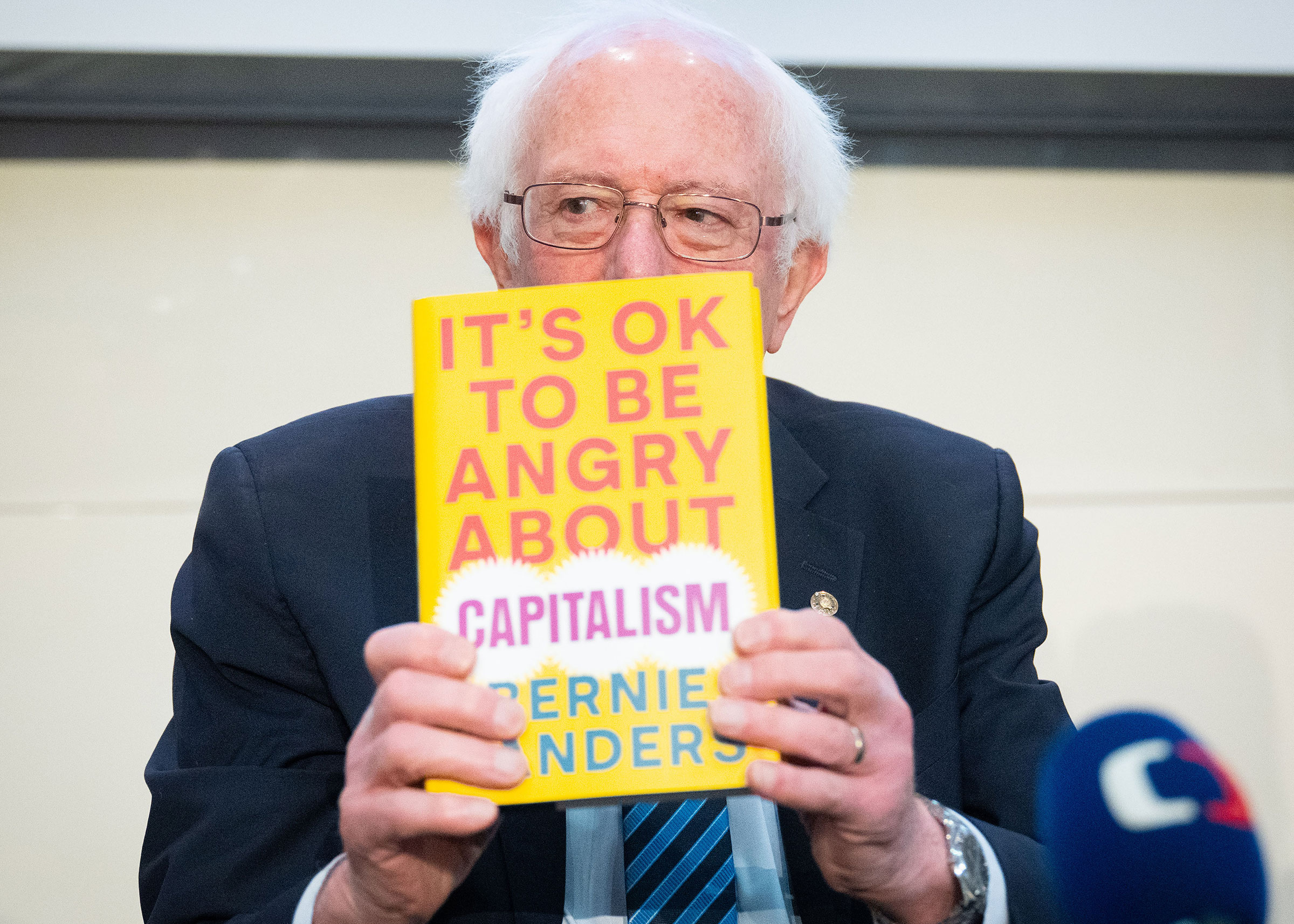

It’s late on a weeknight at The Anthem, a 3,000-seat concert hall on the trendy, upscale D.C. waterfront that recently hosted Bush and the Disco Biscuits. The bar is open, but the venue’s floor is full of orderly rows of chairs, the air is uncharacteristically free of pot smoke, and the merch tables feature no T-shirts or posters, only stacks of the 81-year-old left-wing senator’s latest book, It’s OK to Be Angry About Capitalism. Still, to the overwhelmingly young crowd that has paid $55 to $95 per ticket, they might as well be seeing a rock star—the Mick Jagger of Medicare-for-All.

Callie Whicker, an 18-year-old student at American University, arrived an hour early and settled into her front-row seat, wearing a BERNIE sweatshirt and clutching a knit Bernie doll she got on Etsy. He’s her only source of hope in a coming-of-age that has otherwise been unrelentingly dark: “For Gen Z, coming up through Covid and Trump, we’ve given up,” she says. “Everything’s really bad. But knowing that there are people like him, people with decent hearts fighting for everybody, it’s so inspiring.”

Whicker has pink-dyed hair and wears a mask. Her homemade earrings dangle the words GENDER IS A CONSTRUCT from each lobe. When I ask her if it’s okay to be angry about capitalism, she looks at me like I might have the wrong number of heads. Isn’t it obvious? “Oh yes,” she says with conviction. “Of course, always.”

Sanders’s previous books were titled Our Revolution and Where We Go From Here—hopeful titles that looked to the future. The current one, with its combination of radicalism and neurosis, seems to signal a shift, not just in Sanders but in the ardent following he’s built over the last eight years and two near-miss presidential primary campaigns. His young followers are angry, yes, but they need to be reassured that it’s okay; they want to be comforted, to be affirmed in their feelings.

“We are very, very screwed,” says Farah T., a 30-year-old economist at the World Bank who declines to give her last name. “Angry is a nice word. It’s outrageous. It’s fucked up.” She paid $95 for her primo seat, which, yes, is capitalism—but why are people attacking Sanders for selling tickets when capitalism is responsible for so much worse? Sanders has been her lodestar for as long as she’s been politically conscious. Yet things have only seemed to get worse and worse. “He represents an America I would like to see, but probably never will, unfortunately,” she says.

Sanders’ fans have long admired his consistency, the way he’s been fighting for the same principles since he marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s. But it has perhaps started to dawn on them that that’s another way of saying he hasn’t made much headway in all that time.

“I first got involved in climate activism in eighth grade,” says 19-year-old sociology student Jackie Wells. “Nothing significant has happened since then, and I’m going to another climate rally on Friday. Radical change is absolutely necessary, but I don’t know if our generation is up to it.” She worries that her peers are too complacent, too willing to mistake social-media posturing for activism. But Wells, who considers herself an anarcho-socialist, views the whole political system as a distracting spectacle. “I haven’t posted, like, ‘I’m at the Bernie thing,’ because it’s kind of embarrassing to like a politician,” she says.

“It’s not okay to not be angry about capitalism,” says Nicole Wilder, a 26-year-old editorial assistant. “If you’re not angry, I think you’re just not paying attention, or you’re a selfish person.” Older people, she says, shouldn’t disdain young people’s idealism and fervor for change: “Maybe that’s because a lot of young people actually give a s–t about things other than themselves.”

Read More: What Bernie Sanders Still Has To Prove.

Chelsea Ihnacik, a 38-year-old stay-at-home mom, has been organizing a new Democratic Socialists of America chapter in her rural southern Maryland town. She worries that a Democratic Party that snubs Sanders in favor of milquetoast centrists like Joe Biden is destined to continue losing white working-class voters to Trumpism. “As much as Bernie woke us up to political engagement, the larger system is a monolith that’s not moving,” she says. “Biden betrayed the rail workers and undermined the solidarity of the working class. We’re going to lose those voters to fascism as a result.”

When Sanders comes on, the lights go all the way down, and he stands at the front of the stage in his usual hunched posture, gesturing with his right hand as he holds the microphone with his left. His rap has many of the same themes I remember from his 2016 campaign—the evils of oligarchy and super PACs, the billionaires robbing us blind and never paying a price. But there’s a new emphasis on capitalism’s emotionally taxing nature. “The bottom line, and we don’t talk about this at all, is that the working class of this country is under enormous emotional stress,” he says. “And stress kills.”

Read More: Where Wes Moore Comes From.

Gone, too, is Sanders’ onetime call for “political revolution,” perhaps because he’s become more enmeshed in the system he once sought to overthrow. After 16 years in the Senate, Sanders’ status as the pied piper of the resurgent young left has earned him real credibility—and power—in Washington. This year, he became the chairman of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions committee, a position he intends to make the most of, hauling in pharmaceutical CEOs to testify about high drug prices, holding hearings on the plight of the working class. Next Tuesday, he tells the crowd, he plans to have the committee vote to subpoena Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz for his efforts to suppress unionization—a move that, if successful, would be the committee’s first-ever subpoena of a witness, according to Punchbowl News.

“The American people are standing up, and if I have anything to say about it—and as chairman of the relevant committee, I do have something to say about it—this is just going to be the start,” Sanders says to cheers. Audience members hold up their phones and record snippets of him speaking, like they would at a concert.

At the end, Sanders takes questions. The first one comes from a high schooler named Max who volunteered for his 2020 campaign. “What is your advice to the young people in this progressive movement on how we can keep the momentum of the movement you helped start alive?” Max wants to know.

Sanders looks out at the sea of eager faces, and I wonder if he’s thinking of his legacy—the ideals he’s seeded that will surely outlive him, the fresh-faced students who will keep fighting these fights long after he’s gone. “People often ask the question, what keeps me going?” he says, turning uncharacteristically sentimental. He recalls the millions of people he’s met, the places he’s been, the massive crowd of young people who turned out to see him as the sun set over a small town in rural California, hungry for a message of change.

“So I want to say that, as somebody who gets around the country and has the opportunity to meet with so many people, I don’t want you to become depressed about this country,” Sanders says. “There are millions of wonderful people who are trying to do the right thing. And our job is to educate and organize and create the kind of movement that will breed the kind of transformational change this country desperately needs.”

The lights come back on and Sanders departs, trailed by a lengthy standing ovation. And then the next generation trickles out of the theater, out into the night, out into the despair of the broken world they can’t escape.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Molly Ball at molly.ball@time.com