These are independent reviews of the products mentioned, but TIME receives a commission when purchases are made through affiliate links at no additional cost to the purchaser.

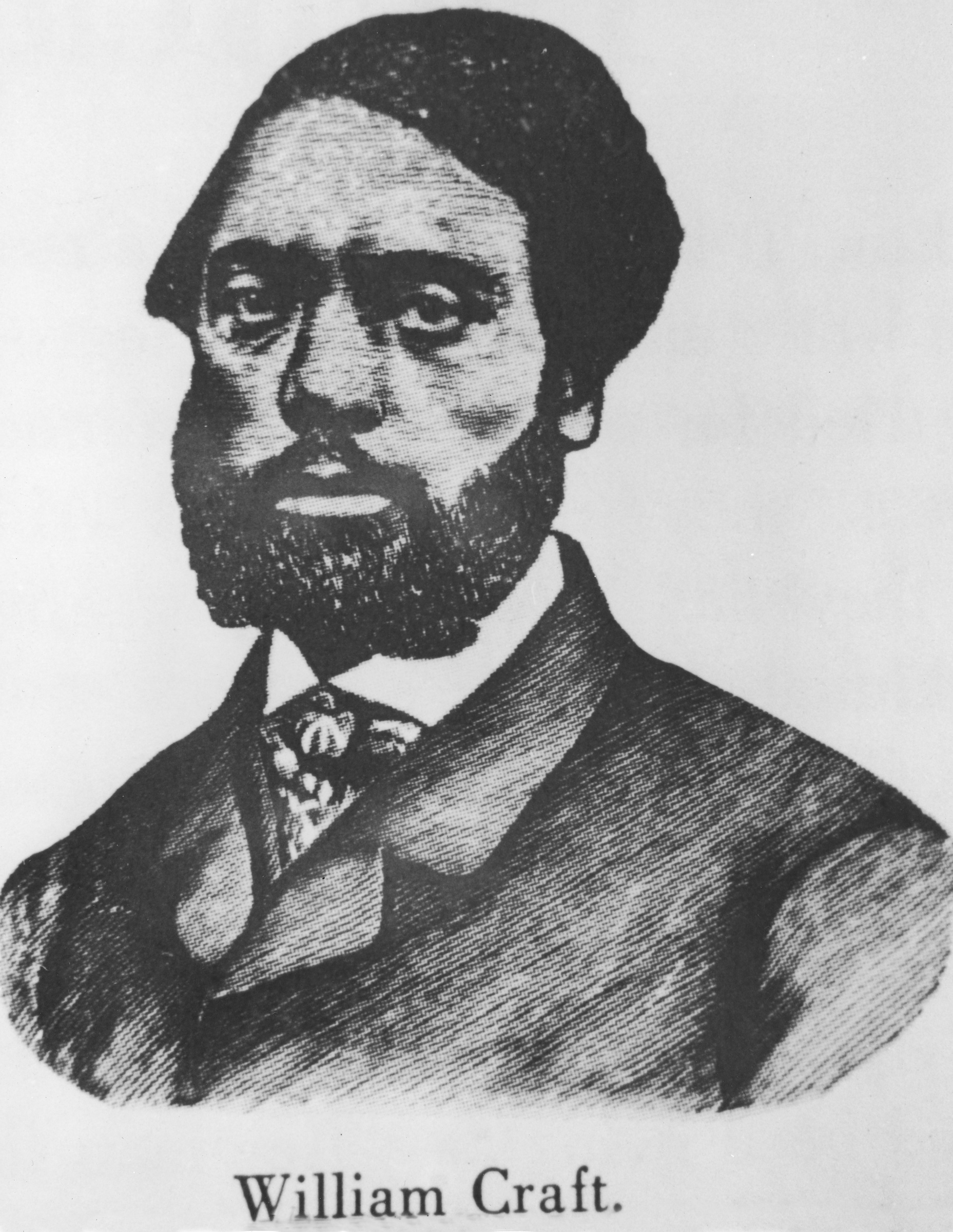

It was a remarkable story: Ellen and William Craft, both enslaved in Macon, Ga., in the 1830s and 1840s, took on a dangerous disguise in order to escape bondage. Throughout their treacherous journey north, light-complexioned Ellen posed as a wealthy, disabled white man and William as her slave. The story was also true. And growing up in 1940s Harlem as the great-great-granddaughter of the Crafts, Peggy Trotter Dammond Preacely heard it often. She and her brother even practiced their reading skills on a chapter about the Crafts’ heroic escape in William Still’s 1872 book The Underground Railroad, one of their mother’s treasured possessions.

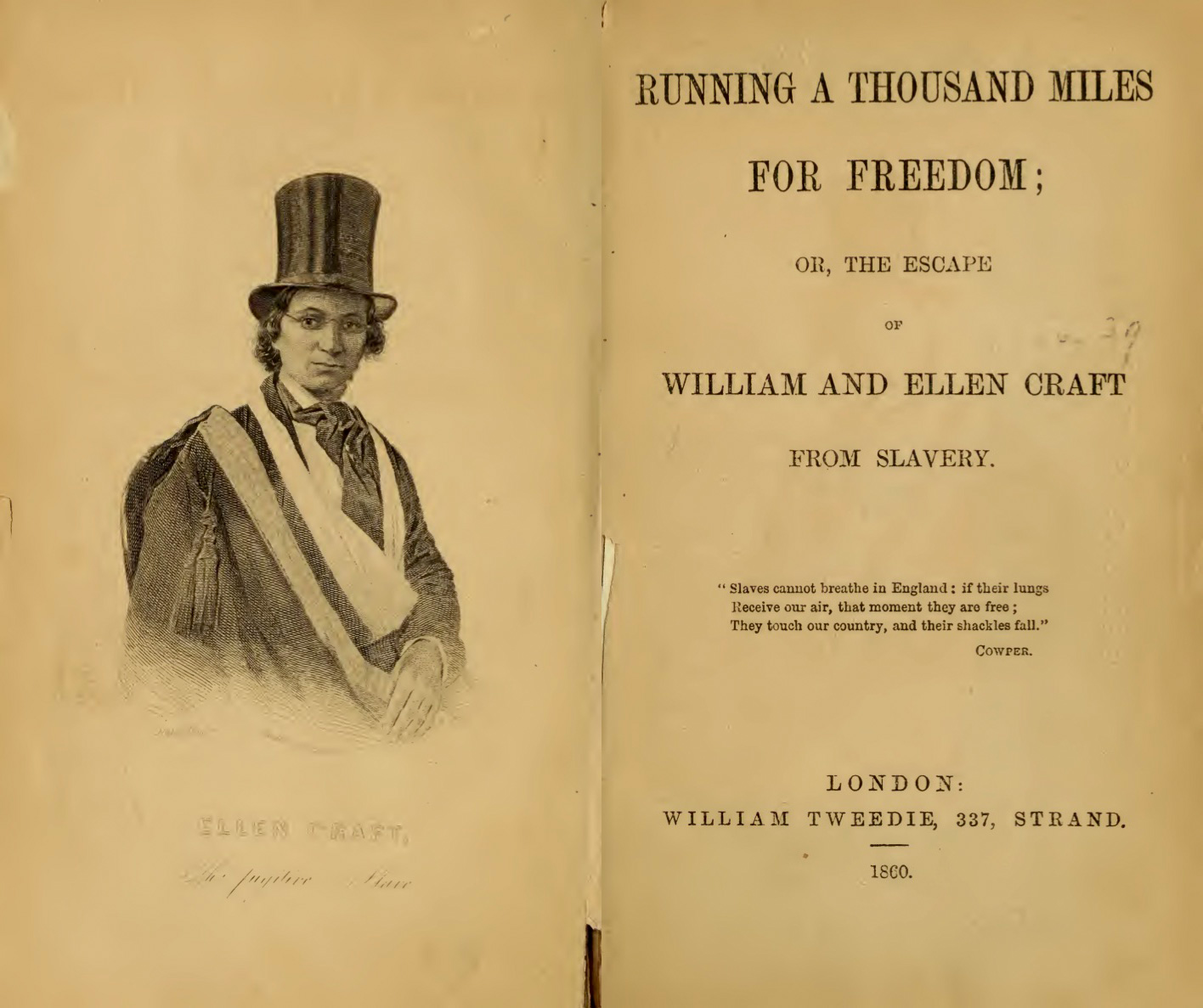

The Crafts themselves wrote a version of their story, Running A Thousand Miles for Freedom, which was published in 1860 in England, where they were forced to seek refuge when they were pursued by slave hunters in the U.S. following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. In detailing their story, they recalled the trauma of childhood separation from their loved ones. Ellen Craft’s first enslaver—her own father—gave her as property to his legal daughter, Ellen’s half-sister. This “gift,” as allowed by the laws of the time, included not only young Ellen but also her “increase”—all future generations of her kin. The couple’s determination to have freeborn children became one of their primary motivations to escape.

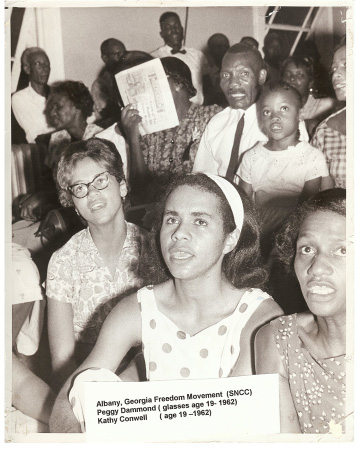

In this, they succeeded, and Preacely—a great-granddaughter of Charles Estlin Phillips Craft, the Crafts’ first child born in England—went on to become a poet, Freedom Rider, and member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Preacely worked alongside activists like John Lewis, Ella Baker, and Bob Moses. She registered rural Black citizens to vote in 1960s Georgia, mobilized action through sit-ins and marches, and, now at 80 years old, continues in her activism today.

I spoke to Preacely multiple times while working on my new book, Master Slave Husband Wife: An Epic Journey From Slavery to Freedom, which tells the Crafts’ story. From our first conversation, she generously told me stories of her activism and the legacy of her ancestors. Here, I asked her to share some of those stories.

Ilyon Woo: You descend from so many notable ancestors—the Crafts, the Trotters, the Dammonds, as well as the Hemingses of Monticello. Can you share a moment when you felt especially empowered by one of them in your own work?

Peggy Trotter Dammond Preacely: Now in my 80th year, I realize there were many significant moments when an ancestor empowered me to take bold action in my life. I felt it when I first walked the picket line in Harlem as a teenager in 1955 to protest the murder of Emmett Till. And I felt it again when I was about to be arrested at a sit-in one cold December night on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1961. I felt that spark of bravery knowing the Crafts had taken their “desperate leap for liberty,” as they describe in their narrative, despite the danger of their recapture at any moment. And that spark empowered me to finally obtain my B.A. when I was almost 33 years old, divorced, and raising my two young children. I had been strongly motivated to complete my degree because of the Crafts’ lifelong pursuit of literacy and learning.

Read More: Cleansing American Culture of Ties to Slavery Will Be Harder Than You Think

The Crafts bravely pursued their dreams of liberty, literacy, and family in the face of so many challenges and obstacles. How did their lives inform your own?

I absorbed and appreciated the Crafts’ story over time and on many different levels, especially when I ventured South in the early 1960s and joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the Freedom Movement. In 1962, I was a field organizer for the Southwest Georgia Voter Education Project. I was very aware that my great-great-grandparents had defied the laws of slavery barely 100 miles and over 100 years from where I was serving, and I felt their courage in my blood. I stepped into their legacy of education and taught local Black sharecroppers how to pass the illegal voter literacy tests designed to deny them their citizens’ right to vote. The Klan burned down our churches where we held our night classes, but the people continued to fill the streets and courthouses in their determination to gain their long overdue political empowerment.

If you could ask Ellen or William Craft one question, what would it be?

As a life-long poet and writer, I have always identified with their gift for and mastery of the written and spoken word. I am so curious if they brought any copies of their book with them when they returned to America in 1869. Or were those copies destroyed in the fire set by the “night riders” of the Klan that burned down their farm and industrial school they had established in 1870 for formerly enslaved families at Hickory Hill South Carolina? To my knowledge, none of the Craft descendants in America saw a copy of the actual book until 1969—more than 100 years later, when it was republished by Arno Press.

Activism clearly runs in your family. Can you talk about your mother’s secret missions, which were kept secret even from you?

My mother, one of the Crafts’ four American great-grandchildren, was a 1938 Bates College graduate, a valued member of the debate team and the first “colored” girl to live in her college dorm. In 1965, she joined the Wednesdays in Mississippi project, [a group] of interracial and interfaith women from the National Council of Negro Women and the Jewish Women’s Council [as well as other groups]. These women traveled secretly by plane to Jackson, Miss., to work behind the scenes with Black and white Southern women to create bridges of understanding across regional, racial, and class lines. These brave middle-aged women were the mothers and aunties of those of us actively working in the student freedom movement at the time, but they never told us they were also risking their lives to work for social and racial justice.

The divisions in our times are often compared to those in the years before the Civil War or on the cusp of the civil rights era. Having roots in these other famously divided eras, what wisdom would you share with everyone living through ours?

When I speak to schools and colleges about my personal social activism and that of my ancestors, I always conclude my remarks with information about what people can do in their own communities. Individuals who seek to help America redeem itself in the face of division and adversity must always take personal responsibility, but also engage in individual action, no matter how small. We have faced political and cultural division as a nation since its founding, but it has so often been the courageous act of just one person who impacts the trajectory of history. One recent example is Darnella Frazier, the teenager who took out her phone on a Minneapolis street to record a video of a white police officer as he knelt on George Floyd’s neck, an act that would ricochet around the world.

I am grateful to have met you, and have learned so much from your stories. What do you think scholars, descendants, artists, and others can do to best connect and maximize our understanding of histories like the Crafts’?

We need to strongly encourage a collaborative and interdisciplinary approach to telling Black American history. Historical truth telling requires a veritable concert of voices to enhance and present what has so long been excluded from the canons of Black historical scholarship. I support and encourage historians and scholars to reach out to descendants as they write and make films about Black ancestral stories. This effort ensures that whatever oral history known only to the family is always considered, if not also included. This practice also honors these families as co-equals in historical reclamation.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com