Amy Stover, a secretary for the Tipton school district in central Missouri, was at her home on Monday night, taking in the Buffalo Bills-Cincinnati Bengals game with her husband, Ken. Since the outcome could determine seeding for the AFC playoffs, including the position for her beloved hometown team, the Kansas City Chiefs, Amy watched the game with great interest.

Suddenly, in the first quarter she noticed that Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin collapsed on the field, after a relatively innocuous hit. The incident sent immediate shockwaves through her heart.

Read More: What We Know So Far About Damar Hamlin’s Cardiac Arrest

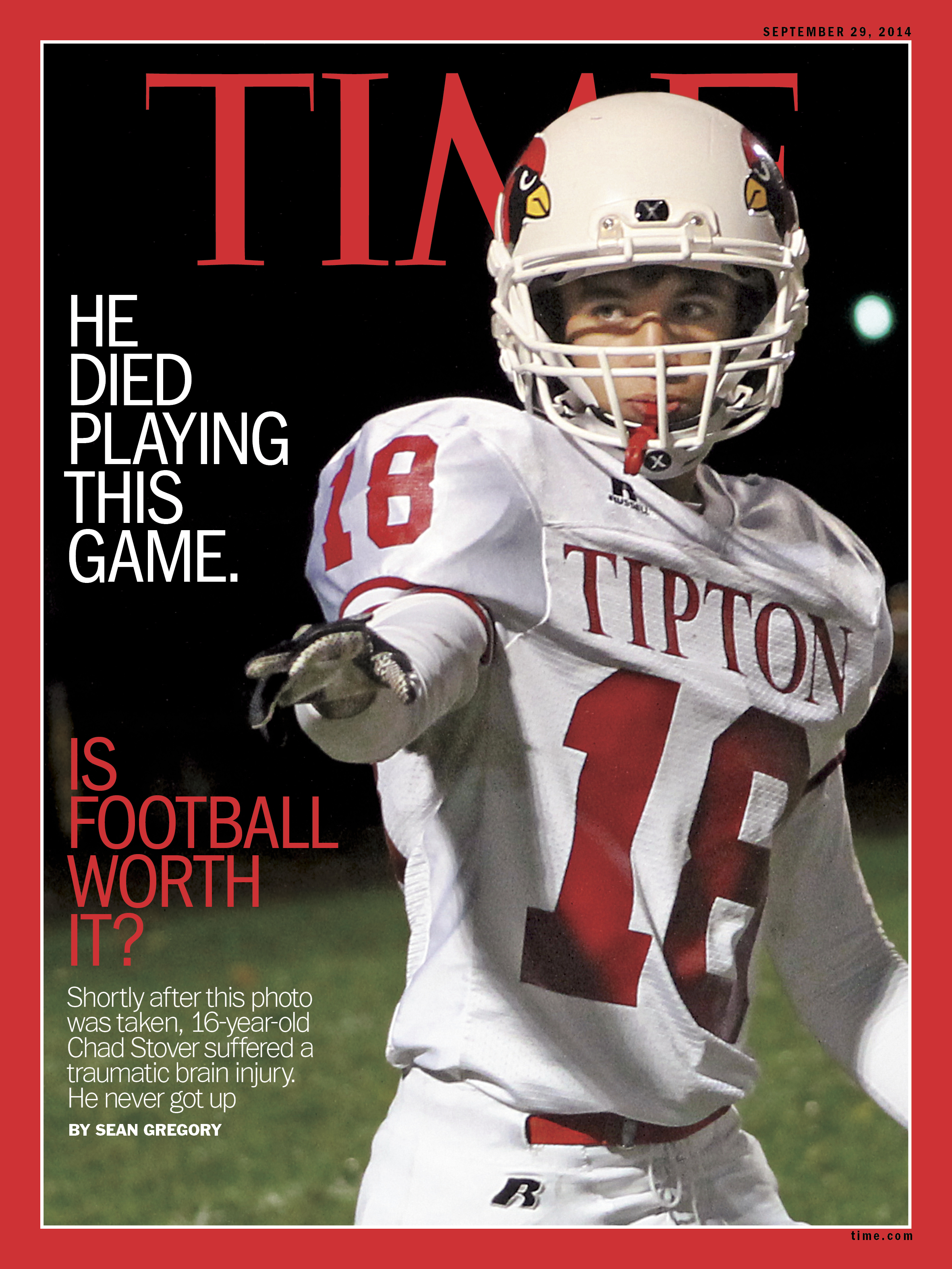

The scene felt eerily familiar. On Halloween night, in 2013, Amy’s son Chad, a 16-year-old defensive back for the Tipton High School Cardinals, made a routine tackle in the fourth quarter of a playoff game. His head collided with the opponent’s thigh, but the force of the blow didn’t seem too extreme.

Hamlin got up after getting hit in the chest, before immediately collapsing while suffering cardiac arrest. Chad went to the sideline after a timeout, returning to the game before collapsing in the huddle. After being administered CPR on the field, Hamlin remains in critical condition at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center. An ambulance arrived at Chad’s game about eight minutes after a 911 call; a fire official administered oxygen. Chad was ferried to a helipad and airlifted 50 miles to the trauma center at University Hospital in Columbia, where he died, of blunt force trauma to the cranium, two weeks later.

On Monday night, Amy saw the closeup shots of Hamlin’s Buffalo teammates and the horror on their faces. “That’s what absolutely brought me to my knees,” she says now. Amy figured some of Chad’s high school teammates were also watching the Bills-Bengals game and were transported to that awful Halloween night. “I knew what those men were feeling,” says Stover. “I knew what all of those players were going through. I knew what what his parents, what his family, what they were feeling. What they were going through at the time. And I had to leave the room. I left and went downstairs and just immediately started praying for all of them. Because the uncertainty of everything that was going to transpire is terrifying. Because you just don’t know.”

Chad Stover’s passing—and his family’s grappling with the tragedy—was the subject of a 2014 TIME cover story on the emergent awareness of football health risks. Eight people died playing football in 2013, the highest toll since 2001, when there were nine deaths, according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research at the University of North Carolina. All were high school players. During the 2013-14 academic year, no other high school sport directly killed even one athlete.

In 2021, four high school players died while playing football, according to the North Carolina center. All four suffered traumatic brain injuries. Eleven other high school players suffered “indirect” fatalities during football-related activities: eight were victims of sudden cardiac arrest, two had heat stroke, and another cause of death was unknown. One college football player died of exertional heat stroke, another had an acute sickle cell crisis.

The presence of first responders at the NFL game may have saved Hamlin’s life. Medical staffing at Chad’s game in 2013 might not have made a difference. Chad had also suffered a more forceful head-to-head blow in the first half of his game and, according to the autopsy, he sustained a level of brain hemorrhage “more usually seen in high-speed motor-vehicle accidents with unrestrained occupants. Such hemorrhages are often fatal, and even with immediate and supportive care severe disability is the best outcome that can be hoped for should death be prevented.”

Still, Amy remains heartened that Tipton, and other school districts around Missouri, have changed their policies and at least require athletic trainers, who specialize in the initial treatment of serious injuries, at football games. Over the past several years, Tipton has partnered with the University of Missouri Hospital to provide athletic trainers for football games. Hamlin’s collapse should remind school districts and youth sports operators that all tackle football games, at any level, should have trained medical personnel, if not ambulances, standing by.

Read More: Where Football Goes From Here

In the summer after Chad Stover’s death, his younger brother, Kenton, decided to give up the game before entering high school. But his younger sister Mandy, who’s now 19, insisted on cheering at football games once she got to high school. “When you live in a small town, football is not just an extracurricular activity,” says Amy. “It’s part of the fabric of your community.” Growing up, Mandy Stover looked up to the Tipton cheer team: she wore cheerleader outfits as a young girl. So she decided to cheer, with the support of her parents. Amy and Ken attended the games, but watching the actual game action proved too difficult. Amy ran the concession stand, and Ken worked the grill.

In her final game as a cheerleader, Mandy Stover marched into the stands to chastise a Tipton parent for encouraging the players to “lead with their heads.” The parent apologized.

Missouri rallied around Chad Stover while he was in the hospital. “Pray for Chad” became a statewide rallying cry. The Diocese of Jefferson City organized a novena—nine consecutive nights of prayer—at the Catholic church in Tipton, and red ribbons were tied around seemingly every tree and signpost in town. California, a nearby school, painted Chad’s number, 18, onto its field. Amy says her family even received well-wishes from Germany and the Netherlands.

Amy knows that given the visibility of Hamlin’s collapse, the outpouring of love for him will be even greater. She knows it will sustain Hamlin’s close family and friends as they endure these trying days. “Knowing that people were caring and concerned for our child was huge,” says Amy. “We lived on that support.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Sean Gregory at sean.gregory@time.com