John Fetterman is a vibe guy. It’s the salt-and-pepper goatee and the tattoos, the shorts and Carhartt sweatshirts instead of suits, the campaign merch with local slang like yinz. (That’s Pittsburgh for y’all.) If the Pennsylvania lieutenant governor and Democratic Senate nominee is able to prevail in November, it will be thanks to his everyman vibe.

The race in Pennsylvania could determine control of the Senate, and for much of it, Fetterman had the clear edge when it came to vibes. He was able to tag his Republican opponent, Dr. Mehmet Oz, a longtime New Jersey resident, with carpetbagger vibes, rich-guy vibes (Fetterman mocked Oz for owning 10 homes and using words like crudité), and quack-doctor vibes (several Fetterman videos lampoon Oz’s history of pushing “miracle cures” as a daytime-TV doc).

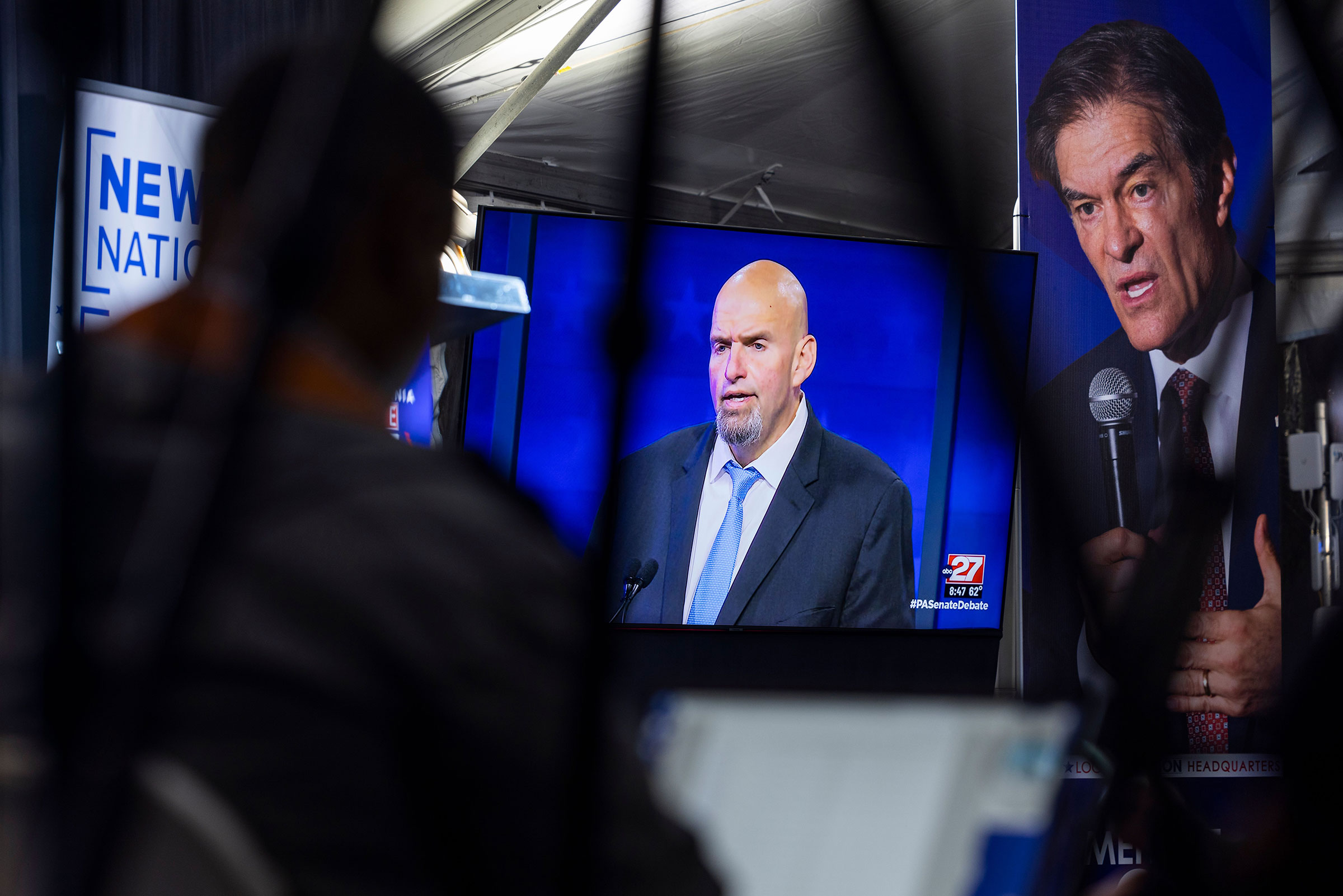

But at the candidates’ lone televised debate on Oct. 25, the vibes on display were very different. Fetterman suffered a stroke in May, and has been dealing with the lingering effects of what his doctor calls an “auditory-processing disorder.” Even with the aid of closed captioning, he struggled mightily to string basic sentences together. Suddenly, a contest the Fetterman campaign had cast as a Pennsylvania native son vs. a slick huckster seemed to morph into a race between a stroke survivor grasping for words and an articulate doctor with plenty of them.

If Fetterman is able to eke out a win in November despite the debate disaster and the political headwinds buffeting the Democrats, it will be a validation of his central political insight. You might call it the Vibes Theory of Politics. The people who decide elections, Fetterman thinks, don’t obsessively follow the polls or listen to wonky podcasts. They vote based on vibes. “People assume that everyone reads Ezra Klein,” Fetterman told me earlier this year. But for most voters, “it’s not like they have their position papers laid out.” He’s hoping they don’t care much about debates, either.

What’s a political vibe, anyway? If a candidate’s character is revealed by their choices, and their personality is observed through their public appearances, then their vibe is a vaporous mixture of both of those things: the general impression they make on a normal person who isn’t paying close attention. (Which is, of course, the vast majority of Americans.) Your vibe is what people who don’t think about politics think about you. Unlike a brand, which can be constructed and curated, a vibe can be enhanced or shaded but cannot truly be faked. An image is crafted by strategists; a vibe is experienced by the voters.

Most very good politicians have a definable vibe. John McCain was the war-hero maverick. Bernie Sanders is the gadfly uncle, cranky but authentic. Mike Pence has a church-deacon vibe that plays with conservatives but not with the MAGA crowd; Pete Buttigieg’s what-a-nice-young-man vibe wins over educated boomers but doesn’t particularly endear him to his own generation. Vibes are so powerful, they can overcome policy differences or political gaffes. Just ask Joe Biden, who won the presidency partly on the strength of his affable-grandpa-with-ice-cream vibe. Or Donald Trump, the ultimate vibes guy, whose I-win-you-lose vibe was powerful enough to propel him through countless political scandals and usher in a new political era on the force of his personality alone.

The 2022 midterms should be a relatively straightforward referendum on the party in power. But the Democratic Senate candidates who may buck the historic trend are doing it partly with vibes. In Arizona, Democrat Mark Kelly maintains his Senate lead partly because of his Buzz Lightyear vibe. The Ohio Senate race is competitive because Democrat Tim Ryan has a hometown-quarterback vibe—a favorable contrast with Republican J.D. Vance’s Trump-suck-up vibe. Democratic incumbent Raphael Warnock is holding his own in the Georgia Senate race at least partly because his pastor vibe strikes many as more appealing than Republican Herschel Walker’s domestic-abuse vibe.

Read More: Herschel Walker and the GOP’s Trump Candidate Problem.

“Voters aren’t issue calculators,” says J.J. Balaban, a veteran Democrat strategist and admaker from Pennsylvania. Issues are obviously important, Balaban adds, but “that tends not to be how people decide. It really is a feeling that people get of: ‘Will this person look out for me? Do I trust them?’”

The Pennsylvania Senate race has been heavier on vibes than perhaps any other key contest in the country. More than $167 million has been spent on ads, and roughly a quarter of those ads have been about the candidates’ personalities, according to an Oct. 24 analysis from AdImpact. Even as consequential events unfolded across America, it has been a vapid election fought through memes and defined by ad hominem attacks, and for much of the summer, Fetterman seemed to be winning it.

But lately the vibes have started to crash up against the real issues at play in the race. Republicans have whacked Fetterman for his flip-flop on fracking. They’ve pummeled him on drug policy—accusing him of wanting to decriminalize heroin and fentanyl—and portrayed him as soft on crime based on his record of supporting clemency during his time serving on Pennsylvania’s board of pardons. Fetterman is the “most pro-murderer candidate in the nation,” says Oz communications director Brittany Yanick. (Fetterman regularly cites his work granting clemency to people unjustly imprisoned and supports marijuana legalization, but a campaign spokesperson says he does not support decriminalizing heroin or fentanyl.)

Then came Fetterman’s stroke. He was off the campaign trail for three months, and when he returned in August, he was visibly affected by the lingering auditory-processing disorder. He mushed words together and relied on closed-captioning aids in interviews. Dr. Oz’s response was ruthless: a campaign spokesperson for Oz’s campaign said Fetterman wouldn’t have had a stroke if he “had ever eaten a vegetable in his life.” Fetterman, in contrast, tried to embody the role of the relatable underdog. His team cut an ad about how the stroke made him realize that “politicians spend so much time fighting about the things that don’t matter.”

“Let’s also talk about the elephant in the room: I had a stroke, he’s never let me forget that,” Fetterman said in one of his smoother moments at the debate. “It knocked me down, but I’m gonna keep coming back up.”

That’s the thing about vibes: they can change.

About 10 days before the debate, I interviewed Fetterman for the first time since his stroke. We had spoken a couple of times a year since 2018, each time on the phone or in person. This time, we talked on Google Meet so he could use closed captioning. “I don’t want to put you on the spot,” he asked. “Do I sound differently after we spoke for years?”

Fetterman remembered details from our earlier conversations with perfect clarity. I detected nothing different about his ability to recall facts, even if he flubbed some words and his communication was slightly garbled. Then again, he has never been particularly smooth on this score. Even before the stroke, Fetterman spoke haltingly, frequently interrupting himself before he finished a thought. He has often seemed self-conscious or tongue-tied, an incongruous personality for his towering frame. An adviser once described him to me as “shy.” He bombed the Democratic primary debate that took place before his stroke, sometimes stammering to defend himself as his opponents presented deft arguments and fluent attacks.

Supporters say this lack of polish is also part of his vibe. “There is no question to me that the fact that he is 6-ft. 8-in., goes around in hoodies, talks like a normal person,” the veteran Democratic political strategist Lis Smith told me before the debate, “that all these things have helped inoculate him from some of the typical attacks you get from Republicans.”

But the effects of the stroke are harder to spin. How, I asked Fetterman, could he serve as a U.S. Senator if he struggles to conduct in-person conversations? How could he huddle with Pennsylvania Senator Bob Casey, or schmooze with Democratic leader Chuck Schumer, or woo Joe Manchin? “Having a conversation, that’s not the same as having an interview on a national network,” he told me. “It’s just about the reality of where I’m at in terms of my abilities to fully make sure I’m being understanding.” (He meant being understood.) When he’s at home with his family, he told me, he doesn’t use captioning. “When it’s very specific kind of questions in that kind of situation, it’s important to fully understand so I can give you the right answer,” he said. “It’s part of understanding exactly what’s being asked. I can understand and bring in words, but just in terms of captioning, it helps to make sure, to be precisely.” (He meant be precise.)

Read More: John Fetterman Charts a New Path For Democrats.

The conversation convinced me that Fetterman’s mind was clear, even though his language was more disjointed than usual. This was also the assessment of his physician: after weeks of demands to be more transparent about his condition, Fetterman released a statement on Oct. 19 from his doctor confirming that he “can work full duty in public office.” (He still refused to release his full medical records.)

But the Fetterman who showed up at the debate sounded much worse than the one I heard in our one-on-one conversation. Facing rapid-fire questions before a national audience, looking uncomfortable in a suit and tie, he was rattled and unsteady, laboring mightily to express his positions. It was a drubbing his team seemed to expect. Ahead of the debate, Fetterman’s advisers circulated a memo attempting to lower expectations for his performance. “We’ll admit: this isn’t John’s format,” they wrote. “John did not get where he is by winning debates or being a polished speaker. He got here because he truly connects with Pennsylvanians.”

Until recently, Oz’s vibe didn’t seem to be going over too well. I finally caught a glimpse of it at a “Safer Streets” campaign event in South Philadelphia on Oct. 13. The candidate had gathered friendly supporters for a discussion on violent crime, at Galdo’s, one of the city’s “newest upscale catering facilities,” which normally specializes in wedding receptions and funeral luncheons. Just beyond a lobby with white leather couches and fake flowers in crystal vases, Oz was delivering a grim diagnosis about Philadelphia’s problems with drugs and crime. Drugs, he warned, were “the gateway to hell.”

The event had the vibe of a daytime talk show. The doctor held court in the middle, and called on various supporters who had been invited by the campaign to share their own experiences. (A recent investigation by the Intercept found that on at least one occasion, a tearful “community member” at Oz’s event was actually a paid staffer.)

“What should we do with all the illegal guns in Philadelphia?” Oz asked the group. After each confessional, the guests would clap, as if they were both talk-show guests and studio audience, and Oz would thank them for sharing and turn back toward the cameras. “One of the most important things a doctor does,” he announced, “is listen.”

It was part of Oz’s ongoing effort to make the race about Fetterman’s soft spots instead of his own New Jersey mansion or his stint promoting products like “sea buckthorn” on TV. He’s trying to transform the campaign from a contest of vibes to a battle of issues, where Oz has a better chance to win in a year when polls show that many of the top ones—the economy, immigration, crime, inflation—favor Republicans.

Read More: The Pennsylvania Senate Race Shows Why Washington Is Broken.

Talking briefly to reporters after the event, Oz recalled asking his father—an immigrant from Turkey—why they were Republicans. “Republicans have better ideas,” said Oz, his monogrammed cuff flashing beneath his suit. “So if I’m in the U.S. Senate, the No. 1 thing to hold me accountable for is: make sure that I have better ideas.”

What exactly Oz’s ideas are can be difficult to discern. He seems to be trying to craft a talk-about-the-issues vibe without actually talking about the issues. He does not have a drug-addiction plan on his website. He didn’t offer his own vision to combat illegal guns at the Safer Streets event, and only released a detailed crime plan on Oct. 24, roughly two weeks before Election Day. Oz’s advisers did not return at least a dozen calls seeking to schedule an interview with him, or return emails seeking details about his drugs plan.

But the man emptying the dumpster outside of Galdo’s was happy to talk. “You can’t trust nothing Oz says. All these pills supposed to help you, it’s a bunch of crap,” says Anthony Matthews, 44. “Ain’t he from Jersey?”

Candidate vibes aren’t the only ones that matter. Party vibes, economic vibes, and historical vibes all play a role too. Across the country, Democratic candidates are struggling to surmount their woke-liberal vibes while Republicans are battling against scary-conspiracy-theorist vibes. The economy has been giving off bad vibes for months, which is usually disastrous for the party in power. Add in the historical precedent of the President’s party losing big in the midterms, and it’s looking like a bad year for Democrats. Polls suggest that Republicans are more motivated to vote than Democrats heading into November, and that the GOP has regained its edge on the generic ballot. “If it is a wave year, vibes matter less,” says Smith, the Democratic strategist.

All this put Fetterman’s vibes offensive to the test. At a recent campaign event in Bucks County, the candidate climbed onstage to the sounds of AC/DC and immediately gestured across the river behind him. “That, over there, that’s New Jersey,” he told the crowd of roughly 1,200 people. “The land of Oz!”

The Fetterman supporters at the event in Bucks County all had different priorities: abortion, union wages, democracy reform. But Fetterman’s “vibe goes a long way,” says Bob Cook, 59, an energy-management technician. “He seems like a real person.” Nathan Frey, who works in manufacturing, nodded to Fetterman’s unique candidate uniform of a hoodie and shorts. “If you wear a suit or something all the time when you don’t have to, that turns me off,” says Frey, 47. Fetterman, he added, has “appeal for people who like his vibe.”

None of the voters I spoke with then seemed concerned about his stroke. Whether that changes in the wake of his debate performance is an open question. At the Bucks County event, Jim Hendricks, a 55-year-old steamfitter, cited Fetterman’s vibes as a key part of his support for the candidate. “It’s just something you can feel,” he says. “He’s not phony at all.”

After the debate, I checked with Hendricks to see if his impression had changed. The performance, he acknowledged, could taint Fetterman’s vibe with voters who were not paying close attention to the race. But his own faith in his candidate had not faltered. “His vibe can still be as an everyday person,” Hendricks told me, “and everyday people have strokes and other issues that they have to fight and battle back from.”

Will voters decide that Fetterman is not up to the demands of the Senate because of his health condition? Will they view his willingness to soldier through those challenges as a test of character that shows he will be a champion for struggling Pennsylvanians? Or will the whole thing amount to a pundit obsession that voters basically ignore? At the moment, it’s hard to read the vibe.

—With reporting by Leslie Dickstein and Julia Zorthian □

Correction, October 26:

The original version of this story misstated J.J. Balaban’s role in Democratic politics. He is a strategist and admaker, not a pollster.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlotte Alter/Philadelphia at charlotte.alter@time.com