Early this summer, I emailed a neighbor of mine, whom we’ll call David, and asked him to go for a walk with me in the park. Although we had lived in the same building on the Upper West Side of Manhattan for more than a decade, we had previously only shared pleasantries with one another in the elevator. But this neighbor’s political views diametrically opposed my own. Given the dire, toxic, runaway path to civil war our nation is currently on, and as a professed conflict mediator, bipartisan bridge builder, and depolarization pundit, I felt it incumbent on me to reach out and try my best to walk my talk. My spouse also talked me into doing it.

I thought my decades of training as a conflict resolution scholar and mediator of difficult moral disputes prepared me for just such encounters. But I spent most of the hour before our date in distress in my bathroom.

When I greeted David in front of our building, he also appeared ill-at-ease. Nevertheless, we headed toward the park for a brief jaunt, anxiety in tow.

On our way, we chit-chatted about our families, and then I explained to him my reason for reaching out. I said that I was increasingly worried about the political divisions in our country and the growing odds of extreme political violence. I was doing my utmost to better understand different perspectives on the situation. He replied, “You mean, you don’t know any Republicans you can talk to.” When I hesitated, he added, “Any Republicans that like Trump, that is.”

“That’s about right,” I admitted.

Then he told me about his upbringing. He explained that he is a devout Orthodox Jew, born in Northeastern France to Talmudic nobility. His grandfather was a village physician and founder of a temple in the Alsace region. He was raised in the U.K., and holds deep conservative values emanating from his religious convictions and his success in global business.

I, then, offered a bit of my own background—a Catholic-born, Irish and French-Huguenot with Chicago, Democratic working-class roots, who, much to his astonishment, married a one-half Jew. David inquired whether my wife’s mother was Jewish and he exclaimed, “So, your children are Jewish!”

“They are,” I replied. This fact seemed to register.

More from TIME

Soon after, we turned to politics. I asked him if he would tell me how he came to support Trump. He said he’d be happy to.

My neighbor then told me his thoughts on the under appreciated accomplishments of Donald Trump, and of the relentless trials and tribulations he had suffered from the main-stream media and other Liberal hacks. He said he had great respect for Trump’s business acumen and executive approach to governing, and that Trump’s attitudes on cultural issues were very much aligned with the Orthodox conservatism of his particular branch of Judaism. As he spoke, David became increasingly animated and agitated, picking up the pace of our walk. He said he believed Obama had dangerously deteriorated America’s standing in the world, until Trump put a stop to it. He thought that George Soros was individually responsible for the extreme levels of violent crime and discrimination against minorities in our society.

I had tried to prepare for our walk. Anticipating an awkward and potentially volatile visit, I did a reflection exercise on my intentions for our time together, which prioritized the goals “listen openly and learn from him” and “avoid becoming too defensive and reactive.” I had also reviewed a chart on the critical differences between debate and dialogue, the latter being more a process of discovery than a win-lose game—a vital ingredient for initiating constructive political conversations today.

Read More: Lincoln Saved American Democracy. We Can Too

I listened during David’s speech. Occasionally, I would ask clarifying questions about points he made, or I would point out when we actually shared common concerns on issues such as gun control. But I also had to actively and repeatedly restrain myself from jumping in to counter points I viewed as misinformation or hyperbole. Instead, I found myself saying, “I see…” a lot.

Then, towards the end of our walk, something remarkable happened. David’s lecture, which had begun with an unadulterated celebration and defense of all things Donald Trump, somehow lost steam. He seemed to have ridden a tidal wave of his enthusiasm to a place where he had talked himself out.

Eventually, he concluded, “Should Trump run for president again in 2024? Probably not. With the stupid moves he made like going after a dead war hero Senator [John McCain] in Arizona and saying those ridiculous things to suburban women about COVID, he should probably just step back and make room for better GOP candidates to step up. Will he? I doubt it. But maybe he should.” About this time, I reminded David that he might want to get back and check in on his wife, to which he stated, “Well, we can go for a few more blocks.”

By the time we got back to our building, my anxiety seemed to have dissipated. I thanked David for his time and willingness to speak, and told him I had a parting gift for him. I had left a copy of a book I’d published recently on overcoming toxic polarization in our front lobby, and handed it to him, saying, “Now, you definitely do not have to read this book. But it explains why I reached out to you in the first place, and I’m glad I did.”

As we stepped into the elevator together, he glanced at the back cover of the book and then said, “Yes, I don’t know what we are going to do about all this polarization. It seems to get worse and worse. But when you feel so passionate about what’s going on, it’s hard to stop or know what to do.”

I said, “I think what we need to try to do is what you and I just did. Meet, as often as possible, with people who see the world differently from us, and just try to keep the conversation going.” He smiled and nodded as the door opened to his floor. I thanked him again, and that was that. For the moment.

OK, so what, right? Big deal. So, I took a walk in a park and talked politics with a neighbor for an hour. Is this what it will take to help our nation avert another civil war? To heal our furious, heavily-armed society?

No. Not a chance.

My walk in the park with David was a warm-up exercise—a slight adjustment, hopefully for us both. It was just one aspect of a month-long experiment that a small group of worried, well-intentioned Americans piloted together this past summer. I am a researcher who studies what it takes for deeply-divided societies like ours to change course for the better. A group of my former students and colleagues came together virtually over four weeks in July to try out a series of exercises and activities gleaned from this research, aimed at breaking out of our toxic patterns. This “Challenge” as we called it, was our attempt to answer David’s quandary about what to do to escape the allure of the vortex of our political passion and blame. We sought to workshop a series of actionable steps that similarly-concerned Americans might take up in their homes, workplaces, and communities to find a way to loosen the grip our current climate of contempt has on us.

Our cloudy, highly-attractive problem

The conversation over why, how, and how much we are polarized in America today is complicated and, of course, contested. However, recent statistics on our state of polarization tell a sobering tale. A national survey published in July 2022 found that one-in-five Americans believed that “in general,” political violence was at least sometimes justified. It also found 42.4% agreed with the statement that “having a strong leader for America is more important than having a democracy” and that “in America, native-born white people are being replaced by immigrants.”

Perhaps most concerning, a survey published last fall found that 80% of Biden voters and 84% of Trump voters view elected officials from the other party as “presenting a clear and present danger to American Democracy.” It also reported that 41% of Biden voters and 52% of Trump voters favor red or blue states seceding from the Union to form their own separate country, with 30% Republicans and 11% of Democrats ready to resort to violence to save the country. That is approximately 20 million Americans ready to fight in a country with 400-plus million guns. And this data was collected before the overturning of Roe v. Wade and the recent FBI raid on Mar-a-Lago, both of which are currently being weaponized by political pundits.

Read more: Analysts Warn Violent Rhetoric After FBI Mar-a-Lago Search Is a Preview of What’s to Come

In fact, this “season” has persisted for over half a century, with spikes in trends of various aspects of political polarization increasing for decades. The list includes surges in our citizens’ affective polarization (hating them and loving us), belief polarization (disagreements over perceptions of truth and fact), ideological consistency (collapse of attitudes across distinct policies into one tribal dimension), geographical and neighborhood segregation (physical sorting of red and blue voters into more homogenous communities), congressional legislative obstructionism (the demise of bipartisanship and functional problem solving in Washington D.C.), political hate speech including on social media, perceptual distortion (viewing them as more extreme than they objectively are), combined with decreases in the presence of cross-cutting structures in communities (found to mitigate civil wars) such as mixed-political families, schools, and playgrounds. These trends are culminating in a stark rise in political violence.

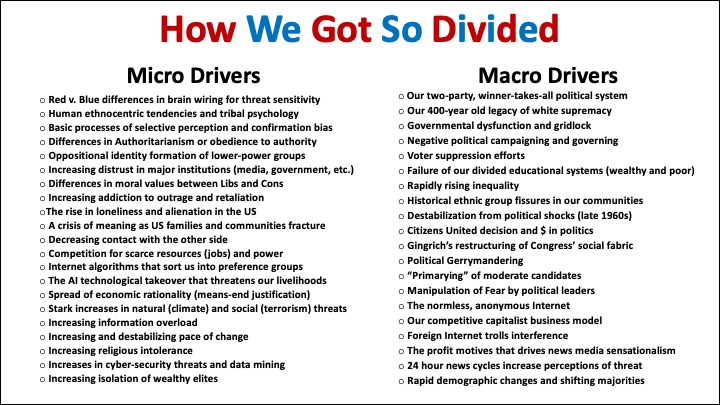

How did we get here? A host of scholars and pundits have weighed in. Most focus in on specific causes in an attempt to identify the main drivers of division within ourselves, within our groups, or within our societal structures—which I list in the table below.

Of course, they are all right to some extent. Studies have shown that all of these factors explain some small but not insignificant piece of the variance that contributes to the depth and persistence of our divisions. But none of them alone can account for the extraordinary 50-plus-year pattern of escalation in political intolerance we are experiencing.

What does account for this runaway calamity is most likely located in the space between these and other drivers. That is, in how they have come to combine together and feed off each other in complex ways to create dynamics—vicious cycles—that are both hard to understand and harder to change. This is similar to how the different elements of a hurricane—low air pressure, warm temperatures, moist ocean air, and tropical winds—can come together to form a powerfully destructive dynamic. Of course, some of the drivers of our divisions are more influential than others, and there are also a variety of bad actors intentionally pulling on some of these levers to make matters worse for us (better for themselves). But, again, they are only part of the problem in a dynamic like this.

What makes matters worse is that across some threshold, this constellation of forces can take on a life of their own. This happens through a process called self-organization when some form of overall order arises from local interactions of parts of the system, which can result in what are known as attractor dynamics. These are essentially strong coherent patterns—of thinking, feeling, acting, and organizing our lives—that draw us in repeatedly and resist change. Attractor patterns are increasingly evident today in Americans’ attitude clustering in partisan terms on a disparate set of 10 distinct policy issues. We are physically relocating and clustering into partisan groups, and we do (and don’t) speak to one another about moral issues in our social networks, mostly within partisan groups.

In America today, our sense of the complex bio-psycho-social-structural factors that are pitting half the country against the other half is really quite simple—it’s us versus them.

Finding a way out

The bad news is that there are no quick, magic-bullet fixes for addressing them. Altering their course often requires a qualitatively different theory of change and a distinct set of skills, including the ability to take a longer-term approach, enact multiple change initiatives simultaneously, track and read feedback, and ultimately get comfortable with failing, learning, and adapting. And a bit of luck. This is essentially how the FDR Administration sought to change the trajectory of the Great Depression in 1933—by shepherding the passage of New Deal banking reform laws, emergency relief programs, work relief programs, and agricultural programs, before moving on to later initiate the multiple programs of the Second New Deal.

However, another bit of bad news is that our government and politicians sit at the epicenter of the problems of political enmity, and institutional and electoral distrust—and in fact are often incentivized to act in ways that exacerbate our divisions—so they are constrained in their ability to address the issues directly.

The good news is that we can. As witnessed most recently with the #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo social movements, and the Civil Rights, Equal Rights, Gay Rights, and Anti-war movements before them, American citizens come together and mobilize for causes that we feel deeply concerned about. When we do so, legislators and business interests often follow. Might stemming the flow of political violence and authoritarianism in our nation and preventing the collapse of our democracy through a second bloody U.S. Civil War be just such a cause?

If so, there is more good news. Three conditions significantly increase the odds of societies like ours pivoting in a healthier direction: First, when major societal shocks—like COVID-19—destabilize us to the degree that we begin to reconsider some of our most basic decision-making assumptions. Second, when enough of us are sufficiently miserable and fed up with the status quo, a state of affairs clearly evident in recent polling. And third, a clear sense of a way out—an alternative way forward that is not too costly and attractive enough to most of us. This, we are finding, is the rub.

Fortunately, today there are thousands of groups and organizations across the U.S. that are working tirelessly to provide a sense of a way out. The majority of these are local, community-based bridge-building groups seeking to bring red and blue Americans together across their differences to talk respectfully.

Read More: 5 Way to Fix America Today

Unfortunately, several key conditions are often missing in the design of most political bridge-building encounters today, including the need for “equal-status contact” between participants—something extremely hard to do in a nation with such profound wealth, income, and educational disparities. It’s an even harder condition to provide in a nation where so many of our leaders, friends, and community members disparage contact with them, so participants often risk being ostracized by their own.

Another significant challenge to political bridge-building today is the lopsided (blue) type of participation they attract. As April Lawson, a bridge builder herself, points out in an essay in Comment magazine last Jan., “Blues assume that if Reds could just be taught what is true, they would be enlightened into Blueness… Reds…smell this train and dislike the tracks.” As David Blankenhorn, one of the founders of the group Braver Angels suggested to me, even the basic terminology used by these groups such as, “dialogue,” “empathy,” and even “bridge building” are early-warning signs for many on the right. As a result, many of these programs face a steep challenge in recruiting this half of our citizenry.

But, perhaps the most significant short-coming of many of these depolarization initiatives is that they are often “one-offs” or short-term encounters. This is where the exposure effect—the more the better—comes in. Take my walk, for example. It’s absurd to think that my stroll in the park with David, by itself, will change anything meaningfully. Time and repetition with these experiences are key. In fact, related research on the effects of cross-cutting structures—local places like playgrounds, schools, sports fields, workplaces, and places of worship that bring people together in contact across their group differences in an ongoing manner—show more robust effects of reducing intergroup intolerance and violence. Similarly, having good friendships across group differences has also been found to have positive effects on intergroup attitudes. Unfortunately, the spaces that provide opportunities for ongoing cross-partisan contact and relationship building seem to be in decline in American communities, both a cause and consequence of our divisions.

The Challenge

In response to the limitations of many current approaches to depolarization, we began to design and test an alternative approach, which recognizes the importance of time and diversity of interventions for sustained behavioral and cultural change. It is grounded in an evidence base that offers us five distinct levers for promoting change with complex problems:

The first iteration of the Challenge was designed around a sequence of activities based on the above principles, which shift the focus each week from your role in the divisions, to your politically-challenged relationships, to your political in-group, to political issues at the community or national levels. It asked participants to commit to spending at least 15 minutes a day—options varied from low to moderate to high effort—for five days a week over a month to do this work, in order to kickstart the much longer journey toward new habit and norm formation and group mobilization. Think of the Challenge as an initial boot camp for participation in our besieged democracy. It included a “Community Dashboard,” which allowed the participants to share their experiences of the activities with others in the pilot, as well as weekly zoom sessions to debrief their involvement.

The upshot: Did it work?

I learned a great deal from this experiment. I learned that despite my considerable training and experience as a conflict-resolution professional, and my genuine desire to lower the odds of political violence, I am a much bigger part of the problem than I imagined. I discovered that I have more extreme progressive views on most political issues than I thought, feel a lot more negative about Republicans and alienated from Democrats than I wish I did, hold significant misperceptions about where Republicans actually stand on issues (between 15-30% gap depending on the issue), and, in turn, have very few (or no) real relationships with Republicans. Oh, and I am much less courageous about confronting members of my own tribe when they misstep or break the rules. This was the story the assessments told me, and I already knew what they were measuring when I completed them! Ouch.

It also turned out that most of the cohort had similarly surprising self-revelations. One member shared how attempting to listen to the radical opinions of her step-daughter resulted in her screaming to herself in her own head and completely derailing her ability to listen.

Another said, “My initial thought was that I would be irritated as it is an individual that typically gets on my nerves. Instead, I discovered we have so much in common. Many of the same fears. Unfortunately, too many of the same wounds and scars. Some of the same hopes and dreams.”

Despite—or perhaps because of—these uncomfortable moments of self-discovery, the overall experience was promising. On our final zoom call, one participant concluded, “I just want to say the whole arc of this experience of having to prioritize thinking maybe a little bit on a higher plain, thinking about how to connect better with people, and definitely, the biggest take-away for me was learning about myself.”

I also learned about the kinds of support we, Americans, will need to escape our mass addiction to outrage. The community aspect of the pilot experiment was a game changer. The activities the group participated in together—the Community Dashboard confessions, weekly zoom dialogues, joint-creation of a Spotify playlist of songs that characterized the Challenge, and so on felt resonant and reparative.

The flexible, “accountability-lite,” format of the Challenge worked well. I encouraged the group early on to share their difficulties, missteps, and disasters with us, establishing a learning orientation within the group—one that leans into and benefits from failure. This opened us up. I also found that some of the most popular activities were invented by participants themselves who “went rogue” and devised their own. The grounding of the scientific principles seemed to provide a platform on which they could innovate and thrive—a gold mine.

I saw how burdensome it can be for Americans today to find the time to complete even brief activities every day, which highlighted the need for some type of “subtraction” for the Challenge, a clear sense of what we could stop doing each day to make time for the activities. Fortunately, one of the activities, “Stop the World and Get Off! Unplug from your devices for a day,” offered a possible solution. One participant reflected that doing so not only afforded her time for the exercises, but it allowed her to be fully present for the day.

I also found that toxic polarization, although increasingly worrisome, is akin to problems like climate change—more distal nightmares that, lacking immediacy, can be easy to put out of our minds. One implication for version 2.0 of the Challenge would be to encourage participants to begin with an inventory of specifically how political polarization is currently damaging their life and relationships, their role in it, and perhaps partners they may wish to reach out to.

I was somewhat surprised to discover that, for many, the pilot was emotionally taxing. One said, “It doesn’t help to take another’s POV when inside I’m screaming at myself [for doing so].” Another commented, “I almost had an existential crisis. I realized that I’m almost too agreeable and depolarized.” This highlighted the vital importance of support to this work. To invite people into this experience comes with a responsibility that must be warranted.

Walking the walk

The summer of 2022 began with the leaked SCOTUS memo on the abortion rights case in May, the formal decision to overturn Roe v. Wade in June, the continuation of the Congressional hearings on the Jan. 6 Capitol insurgency in July, the FBI raid on Donald Trump’s residence at Mar-a-Lago in August, and the seemingly never-ending sagas surrounding new COVID variants and deaths, extreme weather events, and Russia’s now six-month war in Ukraine. These and countless other events provided ample fuel for political weaponization by the news media, social media zealots, and foreign trolls, all while we voted in our contested primaries and consumed the latest propaganda ahead of the midterms. It has been grueling.

At this same time, our small group began work to prepare the ground for opening up more spaces to have these hard conversations. For four weeks, we scrutinized ourselves, reached out our hands to wary others, found the courage to challenge our own groups to be better, and joined local and national chapters of organizations working to hold our democracy together. We struggled, complained, laughed, walked, danced, discovered, were moved, and began to feel a renewed sense of promise. We also came to know that our time together was only one small step on a long road. There will be no quick fixes to the dark storms surrounding us. But today there is more hope and clarity about how to get started.

About a week after my walk with my neighbor, my 25-year-old son, Adlai, got on the elevator in our building with him. My son claims that David had never before spoken to him or acknowledged him in all the years we have lived in the building together. But on this day, David took Adlai in and addressed him. He said, “Please tell your father that I’m reading his book. I’m already several chapters into it. Tell him I’m quite impressed.” My son was flabbergasted.

David and I have now made plans for another walk early this fall.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com