At noon on Monday, March 4, 1861—a day that observers noted had dawned “cloudy and raw” but turned bright and warm—Abraham Lincoln emerged from the 14th Street NW door of Willard’s Hotel, accompanied by President James Buchanan. The two men rode together in an open carriage up Pennsylvania Avenue, bound for the covered platform that had been erected on the East Front for the presidential Inauguration. Double files of cavalrymen escorted the procession to the Capitol. Cross streets had been closed to secure the route in the event of attack. Sharpshooters were stationed on rooftops along the avenue, “with orders,” an officer recalled, “to watch the windows on the opposite side, and to fire upon them in case any attempt should be made to fire from those windows on the presidential carriage.”

An hour later, hatless and adjusting his eyeglasses, Abraham Lincoln, his Inaugural Address in hand, stood and gazed out across a large audience. Federal artillery was deployed on a nearby hilltop. “Plainly, the central idea of secession, is the essence of anarchy,” the new President said. “Why should there not be a patient confidence in the ultimate justice of the people? Is there any better, or equal hope, in the world? In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict, without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to ‘preserve, protect and defend’ it.”

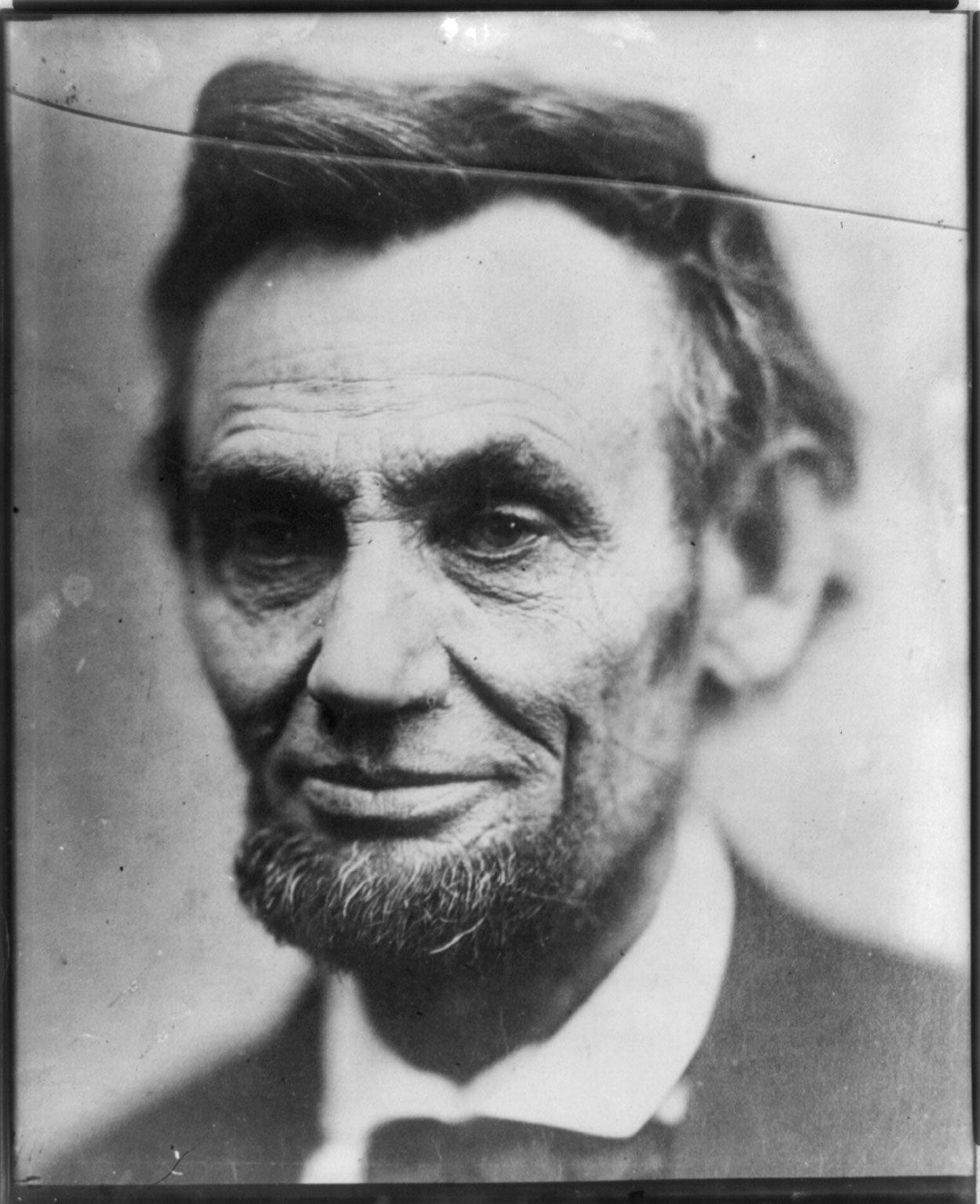

Hated and hailed, excoriated and revered, Abraham Lincoln served as President of the United States in an existential hour. Other Presidents have been confronted with momentous decisions—of war and peace, of life and death, of freedom and power. Yet it fell to Lincoln to adjudicate whether the nation would, in his phrase, remain “half slave and half free”—and whether the American experiment would survive the treason of a rebellious white South that put its own interests ahead of the Union itself.

A President who led a divided country in which an implacable minority gave no quarter in a clash over power, race, identity, money, and faith has much to teach us in our own 21st century moment of profound polarization, passionate disagreement, and differing understandings of reality. Newspaper headlines warn of an impending civil war, and in a recent YouGov-Economist poll 54% of self-identified “strong Republicans” thought “a civil war was at least somewhat likely in the next decade.”

Read More: The Letter in Which Lincoln Debated the Morality of Slavery With Himself

Such fears can seem hyperbolic, and the prospect of great armies forming and clashing in the continental U.S. is blessedly remote. Yet honesty compels us to confront this fact: while civil war in the third decade of the 21st century is unlikely—civil chaos, with episodic violence, is already with us—we do ourselves no favors by pretending that somehow everything will just work out. History can inform our struggle over the survival of democratic institutions and, as important, should help us see the imperative of pursuing justice. For while Lincoln cannot be wrenched from the context of his particular times, his story does illuminate the ways and means of politics, the marshaling of power in a democracy, the persistence of racism, and the capacity of conscience to help shape events.

Get a print of the Lincoln cover here

He governed a nation in which a violent and vociferous element was captive to its own visions and controlled by its own interests. “Domestic slavery is the great distinguishing characteristic of the southern states, and is, in fact, the only important institution which they can claim as peculiarly their own,” Abel P. Uphsur, a Virginian who served as Secretary of State under John Tyler, wrote in 1839. White Southerners dreamed of a slave empire headquartered in the American South but stretching to Cuba, to Mexico, to Central and South America. Such a white-dominated new nation, a Charleston, S.C., newspaper wrote, would ensure slaveholders “a great destiny.”

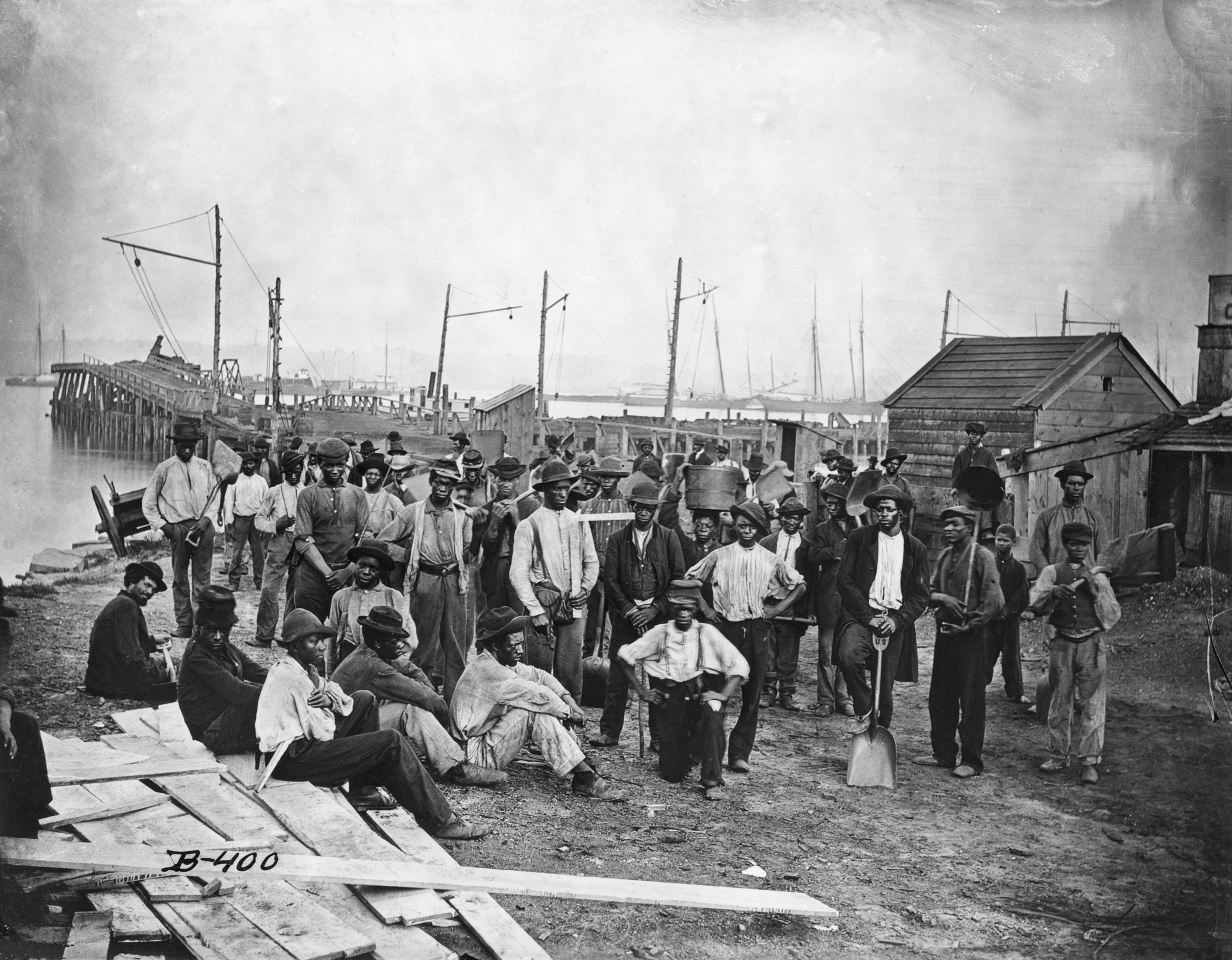

Lincoln kept the American experiment in self-government alive when it seemed lost. He did not do so alone. Ordinary people, Black and white, sacrificed to preserve the Union against the designs of the rebel South. But Lincoln was instrumental, and his ultimate vision of the nation—that the country should be free of slavery—was informed by a moral understanding of life. To him, America ought to seek to practice the principles of the Declaration of Independence as fully as possible, for the alternatives were so much worse. What if the constitutional order had failed and the Union permanently divided? A durable oligarchical white Southern slave empire, surely strengthened and possibly expanded, would have emerged from the war; and, as Lincoln saw, the viability of self-government would be in ruins.

Lincoln did not bring about heaven on earth, nor does he stand as a paragon of equality and justice for all. Yet he defended the possibilities of democracy at an hour in which the means of amendment, adjustment, and reform were under prolonged and almost successful assault. Lincoln’s motives were moral as well as political—a reminder that our finest Presidents are those who are committed not only to the pursuit of power but also to bringing a flawed nation closer to justice. Such requires an understanding that politics divorced from conscience is fatal to the American experiment in liberty under law.

More from TIME

This lesson is essential for us in today’s unfolding democratic crisis. The forces of unchecked power are self-evidently in the ascendant, and they are the controlling element of one of our two major parties. The past is not always prologue, but history suggests that our divisions are as deep as they have been since Lincoln’s time—and thus his experience repays consideration.

When an element within the nation seeks its own power and its own way over and above any other factor, that element must be confronted, or else everything might be lost. In exploring Lincoln’s example we can see how arduous American democracy is, and we can glimpse what must be done to preserve it. An American President must be committed to something larger than his own hold on power. And the American people must be willing to accept the give-and-take of the constitutional order, even when—especially when—events and moral claims call on us to give rather than to take.

Lincoln is often depicted as either a secular saint, the savior of Union, and the Great Emancipator, or as a calculating political creature imprisoned by public opinion and white prejudice. The truth is more complicated. Driven by the convictions that the Union was sacred and that slavery was wrong, Lincoln was instrumental in saving one and in destroying the other.

A man of power, he ultimately demanded that the nation follow a moral path through the brute physicality of Civil War. His “ancient faith,” Lincoln once said, “teaches me that ‘all men are created equal’ and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.” In common usage, to say something is moral is to say that it is about the degree to which one’s conduct is in harmony with the commandment that one ought to do unto others as we would have them do unto us. From Plato to Kant, the substance of what is known as the Golden Rule—one common to the world’s religious and moral traditions—has occupied philosophers across the ages.

Lincoln’s own sensibility—both moral and political—was founded on this injunction. “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master,” he once said. “This expresses my idea of democracy.” For Lincoln, a world in which power was all, in which the assertion of a singular will trumped all, in which force dictated all, was not moral but immoral, not democratic but autocratic, not just but unjust.

In the White House, Lincoln defended Black Americans as fellow human beings whose fundamental rights were protected in the Declaration of Independence—hardly the most common of arguments in his time. Yet he sometimes spoke in racist terms, did not immediately press for Black people to be afforded the rights of citizenship enjoyed by white people, and proposed their voluntary removal offshore. And Lincoln portrayed his decision on wartime emancipation as a last resort based on military rather than moral considerations.

Read More: The First Secret Plot to Kill Abraham Lincoln

This was the pragmatic Lincoln that Frederick Douglass understood. “Viewed from the genuine abolition ground,” he said in 1876, “Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull, and indifferent: but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical, and determined.” As Reconstruction gave way to Jim Crow segregation, Douglass’s opinion was less widely shared. “Abraham Lincoln was a Southern poor white … poorly educated and unusually ugly, awkward, ill-dressed … cruel, merciful; peace-loving, a fighter; despising Negroes and letting them fight and vote; protecting slavery and freeing slaves,” W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in 1922. “He was a man—a big, inconsistent, brave man.”

It is true that Lincoln did not seek immediate abolition; neither was he a radical racial egalitarian. He was, rather, a gradual emancipationist who wanted to compensate slave owners. The antislavery Lincoln was born in, and came to lead, a nation in which anti-Black prejudice was a fact of life. There was hardly a mighty current of sentiment abroad in the land to emancipate the enslaved and extend citizenship to the newly freed in a Promised Land of racial and civil equality. Yet to depict Lincoln as only a reluctant warrior against slavery fails to do him justice. He did not waver from a morally informed insistence that slavery be put on a path to “ultimate extinction.” He maintained this position to his political detriment throughout the 1850s—he won no major office between a single term in the U.S. House and his election to the presidency in 1860. Vitally, he refused to retreat from his antislavery commitment during the crisis over secession in 1860–61—a time when a purely political man might have done—and he stood by emancipation after 1862, declining to give in to pressure for a negotiated peace with the Confederacy in order to end a devastating war. He campaigned on an abolitionist constitutional amendment in 1864.

Anathema to much of the white South and to its allies in the North, Lincoln frustrated abolitionists who were more advanced than he on freedom and egalitarianism. He was attacked for defending a Constitution that protected slavery and for fighting to preserve a politics in which racial prejudice was a predominant factor. The implication of such criticism was that Lincoln made a fetish of the Union at the expense of pursuing true justice. The problem with such a view, however, is that without Union there could be no freedom for the enslaved. Had Lincoln simply bade the South well and set about creating a separate, free nation, he would have consigned millions of enslaved Black people and their progeny to unrelenting and unrepentant masters. Douglass wrote that he would “prefer the Union even with Slavery than to allow the Slaveholders to go off and set up a Government.” A successful Confederate States of America might well have expanded its reach southward. Thus, after Jan. 1, 1863, Lincoln’s war for Union was simultaneously a war for Union and for emancipation in the seceded states; after congressional passage of the 13th Amendment in early 1865, it became a war for Union and for emancipation for all.

Lincoln understood the magnitude of the issue, and he knew that upon its resolution rested the fate of American democracy, if American democracy was to be the project by which the nation sought to live up to the promise of the Declaration. “Slavery is not a matter of little importance,” Lincoln said in 1858. “It overshadows every other question in which we are interested.” As he confronted the question, he juggled political reality and his own moral convictions—convictions that he hoped the nation would come to share.

The work of a democracy is to lead a sufficient number of individuals to share a moral vision about power, liberty, justice, security, and opportunity in the hope that people—and peoples—might be in closer harmony with the good. As a multitude of individuals, a nation possesses a collective conscience—one that is manifest in how that nation chooses, through the means of politics, to view rights and responsibilities.

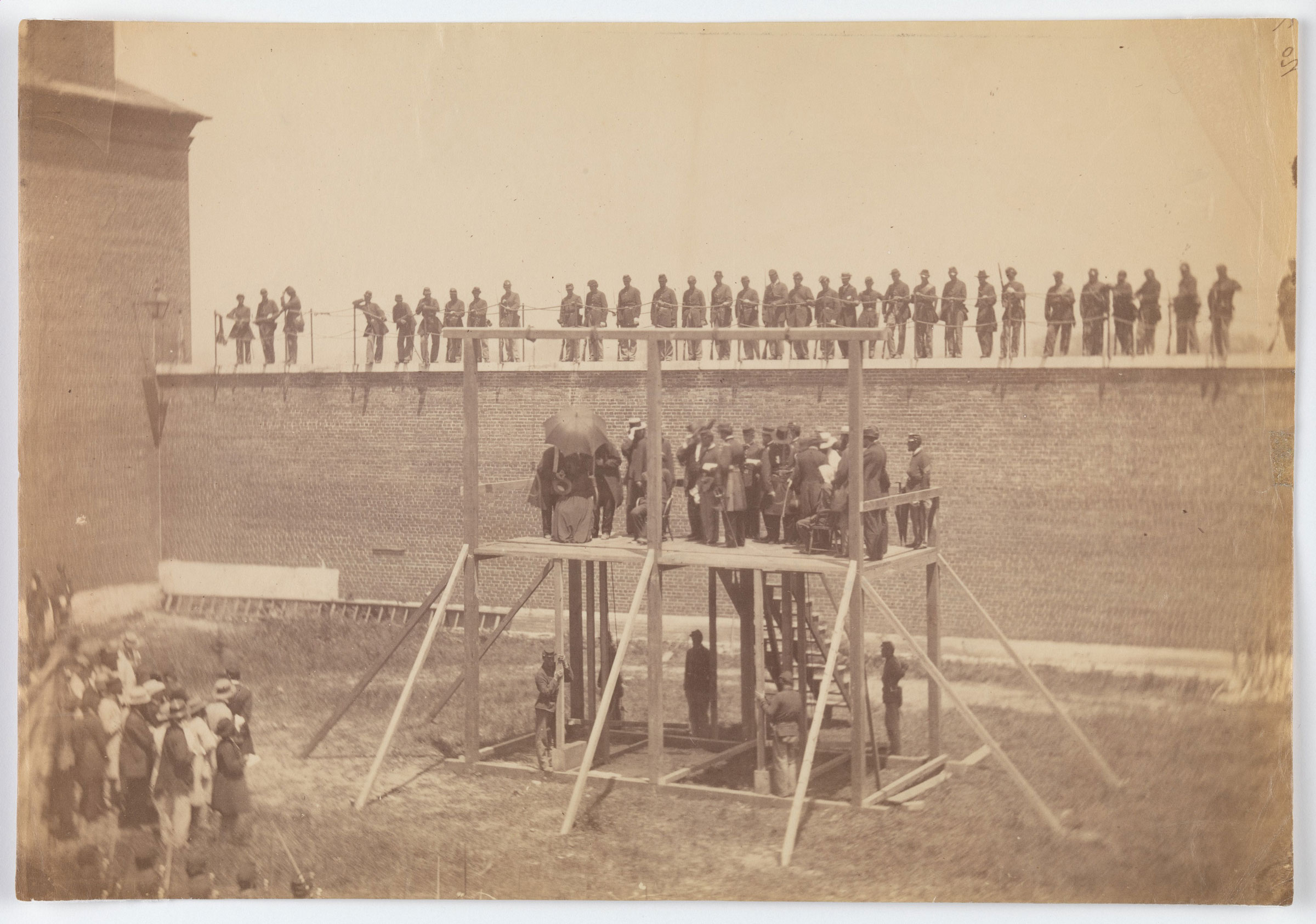

In the 1860s, war was required to bend the arc of the moral universe toward justice. That is the great fact of the American story: secessionist white Southerners chose to fight and to die rather than surrender an aristocracy of race. The Civil War, Lincoln told Congress in 1861, “presents to the whole family of man the question whether a constitutional republic, or democracy—a government of the people by the same people—can or cannot maintain its territorial integrity against its own domestic foes.”

The battle of the third decade of the 21st century is, for now, of a different scale. But we have already seen attempted insurrection, and many adherents of one of our two major political parties refuse to accept the legitimacy of the 2020 election, setting the stage for subsequent denials of reality as soon as next month’s midterms. While the Civil War era, therefore, is not a precise analogy, we would be derelict in our duties as citizens if we did not reckon with what Lincoln reckoned with: the often self-sacrificing demands of decency and of democracy.

On that March Monday in 1861, Lincoln spoke to the ages: “We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be -enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” The words are immortal, as are angels—but Lincoln teaches us even now that those angels will not take up the cause—unless we do too.

Meacham, a Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer and professor at Vanderbilt University, is the author of the new book And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle, from which this essay is adapted.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com