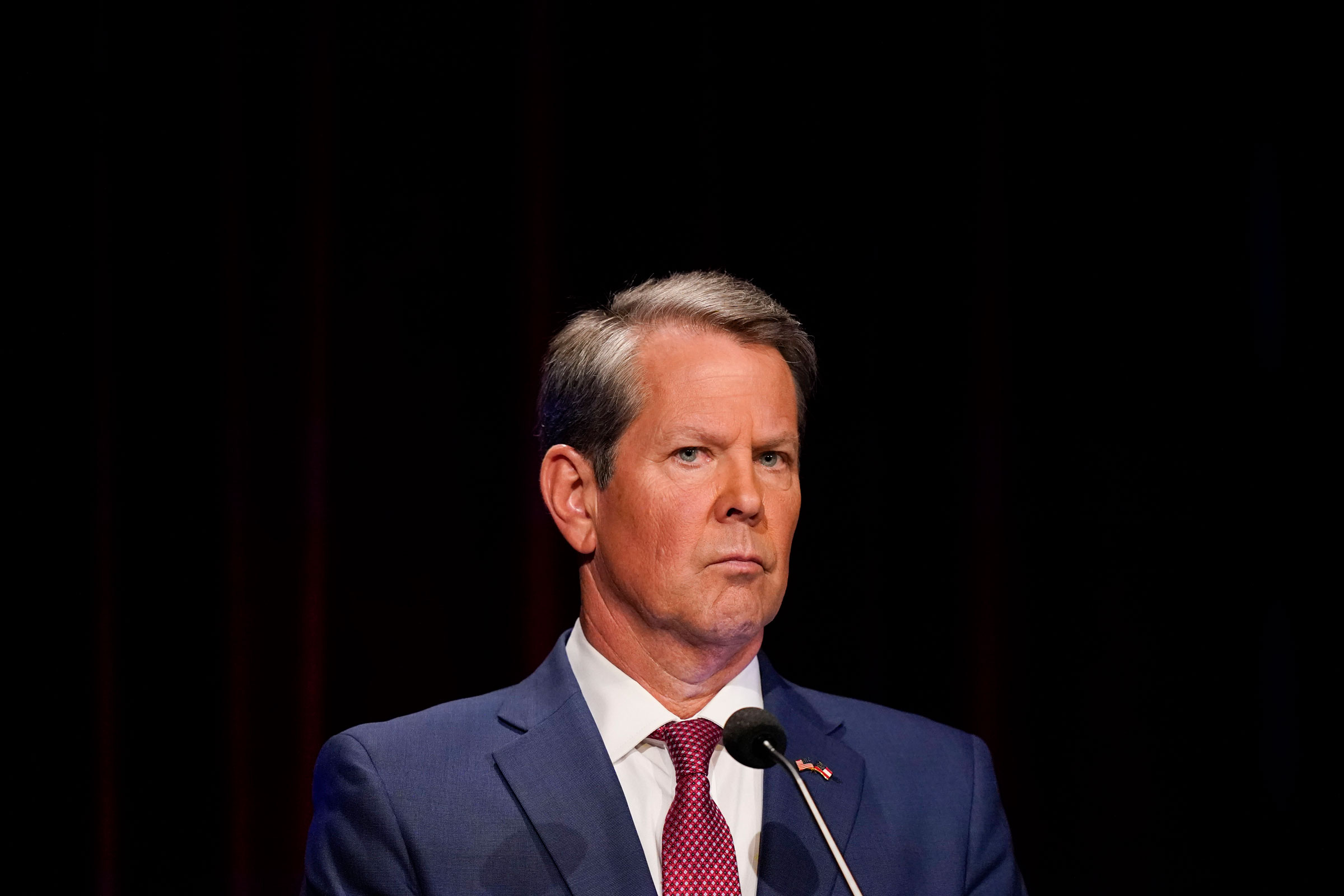

It’s not easy to make Brian Kemp laugh, but at the mention of Donald Trump, the governor of Georgia lets out a rueful chuckle. “Well, heh-heh, I don’t know,” he drawls, leaning against the lunch counter at Charlie Joseph’s chili-dog stand in the western Georgia town of LaGrange. “You’d have to ask him about that.”

Kemp is perched on a red-leather-and-chrome stool, reflecting on the trials of the past four years—many of them at the hands of the former President. Once upon a time, the 58-year-old Republican was a loyal Trump ally. But that was before he declined to help overturn the 2020 election, prompting Trump to mount an all-out campaign to defeat him. “I guess he got mad at me,” Kemp says with a shrug.

That’s an understatement. Trump put more money and effort into unseating Kemp this year than any other Republican who has crossed him, even Liz Cheney, the crusading anti-Trump congresswoman. In today’s GOP, the former President’s endorsement is usually a golden ticket, and his enmity is almost always the kiss of death. The vast majority of Republicans believe his false election claims. When he turned on Kemp, many figured the governor’s career might as well be over.

But Trump’s attempt to oust Kemp failed spectacularly. The governor clobbered Trump’s handpicked candidate, former Senator David Perdue, by more than 50 points in the May primary. And far from damaging Kemp, the feud with Trump may have left him better off politically than he was before, burnishing his brand with Trump-skeptical independent voters. That makes Kemp the rare—perhaps the only—GOP pol to have used Trump better than Trump used him.

The hard-fought primary, Kemp tells me, was a blessing in disguise. “It gave me an opportunity, quite honestly, to remind people of what my record was,” he says. “And what I told them I’d do when I was running, I actually did as their governor. And I think the longer things went, the more people realized that, and that paid off big.”

Now, as the general election nears, Kemp looks poised to get his revenge. He is favored to win his rematch with Democrat Stacey Abrams more convincingly than four years ago. Back then, Kemp eked out a victory in a race Abrams refused to concede, insisting it was tainted by voter suppression. This time the dynamics are in some ways the opposite. In 2018, Kemp was the Trumpy candidate accused of subverting democracy; now he’s the candidate who defied Trump to defend it, and his opponent is the one accused of election denial. Despite being outspent nearly 2-to-1, Kemp is ahead by an average of about 6 points in the polls.

Read More: 5 Governors’ Races That Will Define the Midterms.

“The greatest thing ever to happen to Brian Kemp was when Donald Trump decided he hated the guy,” says Erick Erickson, the conservative activist and Atlanta-based syndicated radio host. In 2018, Trump’s endorsement was all many Georgia voters knew about Kemp, but “anyone who knew Brian knew he was way more reasonable—a conservative but not a firebrand,” Erickson says. “When Trump went after him, it put those suburban voters who don’t like Trump at ease. By his record, he’s been able to show them who he really is.”

More from TIME

Kemp never stopped being a lib-triggering conservative; he even kept up his crusade against the phantom threat of voter fraud, signing an election law that Democrats including President Biden see as racist voter suppression. Kemp seeks no credit for protecting the vote and saving the election. He argues he was just doing his job, and would prefer to talk about almost anything else. “I have always followed the law and the Constitution,” he says. “I believe that that oath I took is better and bigger than any person including myself, and it’s certainly bigger than any political party.”

But had Republicans like Kemp not stood firm when it counted, the 2020 election—the first in American history not to result in a peaceful transfer of power—could have been a far worse crisis. In an age when pundits and scholars fret that democracy is hanging by a thread, it is Kemp’s approach, not Cheney’s, that may hold the greatest promise of bringing the GOP back to reality: not going to war with Trump, but consigning him to the past, by ignoring his provocations and giving his voters something else to believe in.

At the lunch counter, Kemp’s blue button-down shirt is embroidered with a “Keep Choppin’” logo featuring the Atlanta Braves’ tomahawk. It’s a gesture of support for a team in a pennant race, and a not-so-subtle swipe at the Biden Administration’s suggestion that a “conversation” about the team’s name was in order. It is also, perhaps, an apt description of his M.O. He defeated Trump the way he does everything, the way he plans to win this election as well: by plugging away, relentlessly focused on the goal and refusing to engage with distractions. “This year is completely different” from 2018, he tells me. “You know, I have a record. People know the real Brian Kemp.”

Kemp orders a chili cheeseburger to go and eats it in the car on his way to his next event of the day, an economic-development announcement at the Kia plant in West Point. Georgia’s economy is thriving, having just experienced the two best job-creation years on record. Multibillion-dollar electric-vehicle manufacturing plants for Hyundai and Rivian are set to break ground soon. Today, Kemp announces from the stage, Georgia has been named the No. 1 state for business for the ninth year in a row by Area Development magazine, a trade publication for site-selection professionals.

Once upon a time, before Trump turned the party into an insult-comedy chaos machine, this was a GOP governor’s principal job: to keep his state friendly to the forces of capital. “For over 35 years, we’ve been small businesspeople,” Kemp tells the crowd. “That’s why I first ran for governor, and I promised to make economic development in all parts of our state, especially rural Georgia, a priority. And in the four years since, we have been delivering on that promise.” Kemp is particularly proud of having been on the leading edge of defying early COVID-19 restrictions in 2020. His actions drew an avalanche of criticism at the time, but have proven popular in the state, and today they constitute the core of his reelection pitch, cited as evidence of his ability to make tough decisions and not back down.

Kemp can be personable, but he is not a politician who exudes joie de vivre. He smiles effortfully and stays relentlessly on message. His persona communicates nothing so much as grim determination. His wife, Marty, says he washes his own clothes and wakes at 5 a.m. to clean out the stables on their farm. Friends and colleagues describe him as maniacally hardworking and focused, sometimes to a fault: once he makes a decision, they say, it is nearly impossible to change his mind. In high school football, he played left tackle despite his relatively small stature, his friend and team co-captain Daniel Dooley recalls. “He was tenacious and tough,” Dooley tells me. “He wasn’t the rah-rah guy—that was me. He was the leader by example. Everyone was always bigger than him, but he got after them like a gnat, and they couldn’t get him off once he got on ‘em.”

A native of the liberal college town of Athens, Kemp was a homebuilder and developer before getting into politics two decades ago. He served in the state senate and then as secretary of state, responsible for election administration, before deciding to run for governor in 2018. Originally seen as the underdog in the six-way Republican primary, Kemp styled himself as a “politically incorrect conservative.” In one ad, he held a shotgun in his lap while interrogating a supposed would-be suitor of one of his three daughters. In another, he hung a plaid-shirted elbow out the window of his F-350 pickup, boasting, “I got a big truck, just in case I need to round up criminal illegals and take ‘em home myself.”

Buoyed by Trump’s endorsement, Kemp won the primary in a runoff. Trump was convinced Kemp owed him his political career. “I got this guy elected,” Trump boasted at a rally in Georgia last year. But Kemp says that wasn’t really the case.

“I mean, look, he endorsed me with eight days to go,” Kemp tells me. “There was public polling that had us up 6 or 7 points. And I think it was because I worked hard. I think a lot of people underestimated how well I knew the state. That’s what ended up winning the race for us. Obviously, when Trump endorsed, it made it a blowout. But we were going to win regardless.”

In the general election, Kemp’s cartoonish Trumpiness provided a perfect foil to Abrams, a rising Democratic star with a compelling backstory and talent for political oratory. A state legislator turned voting-rights activist, Abrams accused Kemp of subverting democracy: as secretary of state, he’d purged more than a million voters from the rolls and suspended more than 50,000 voter registrations—most of them Black voters—just before Election Day. Good-government advocates also cried foul at his overseeing an election in which he was a candidate. When Kemp won by 55,000 out of nearly 4 million votes, Abrams declared the result tainted and refused to concede—an episode many on the right cite as a precursor to Trump’s baseless stolen-election claims, though Abrams never tried to overturn the result or thwart the transfer of power. “She accused me of being a racist and a voter suppressor,” Kemp tells me dryly. “People know a lot different now.” On Sept. 30, a federal judge rejected Abrams’ lawsuit stemming from the 2018 vote.

In retrospect, that election, centering as it did on issues of voting rights and democratic legitimacy, was the first in a series of election crises that have come to define Kemp’s career. In 2020, after Trump lost Georgia by nearly 12,000 votes, he tried in vain to reverse the result by pressuring state officials. Trump implored secretary of state Brad Raffensperger to “find” enough votes to change the outcome and urged Kemp to call the legislature into special session to appoint new electors. Both refused; Kemp said it was “not an option under state or federal law” and would be “unconstitutional and immediately enjoined by the courts.” The result held, despite an intense campaign of threats, harassment and attempted hacking by Trump and his minions. In the election’s aftermath, as Trump continued to sow doubt with GOP voters, Democrats swept both U.S. Senate seats in a January runoff, giving them control of the upper chamber.

Read More: Conspiracy Theorists Want to Run America’s Elections. These Are the Candidates Standing in Their Way.

Last year, Georgia’s Republican legislature passed a controversial new law overhauling elections in the state. It curtailed absentee voting while expanding early voting and restructuring election oversight, including removing the secretary of state from the election board—a change some experts worry could make it easier for bad actors to overturn future results. President Biden called the law an “atrocity” and “Jim Crow in the 21st century.” The Justice Department sued for alleged racial discrimination. Corporations pledged to boycott the state, and Major League Baseball moved the All-Star Game scheduled to be held in Atlanta that summer. Kemp, Raffensperger and their allies have argued that the criticisms are overblown—Georgia affords voters far more opportunities to cast a ballot than New York, for example—and that the law was needed to patch weaknesses in the system and restore voter confidence.

Still, Trump was determined to punish Kemp for what he saw as a betrayal. He personally implored Perdue, who had just lost reelection to the Senate in the runoff, to take on Kemp. Once Perdue got in the race, Trump funneled more than $3 million to his campaign—by far the most he has lavished on any candidate this cycle. (He gave Cheney’s opponent, Harriet Hageman, less than $1 million; most of his candidates get nothing more than the endorsement as Trump sits on more than $100 million in unused political funds, drawing complaints from the GOP establishment. This week, a Trump-backed super PAC reportedly purchased about $400,000 worth of ads in Pennsylvania and Ohio.)

But while Cheney chose to make herself a martyr to the anti-Trump cause, Kemp chopped away at the challenge. He rallied Georgia’s power structure around him, locking down influential donors and doling out appointments to erstwhile Perdue allies—even the former senator’s cousin, Sonny Perdue, the former governor and agriculture secretary, whom Kemp named to head the state university system. By the end, not even Herschel Walker, Trump’s handpicked U.S. Senate candidate, or Marjorie Taylor Greene, Trump’s No. 1 fan in Congress, would endorse Perdue.

Read More: On the Campaign Trail With Marjorie Taylor Greene.

While Trump blasted him as a “turncoat,” a “coward,” and a “complete and total disaster” who would “go down in flames at the ballot box,” Kemp refused to engage the former president’s attacks. Instead, he would simply repeat that he supported Trump’s policies and wished he had won in 2020. When GOP voters echoed Trump’s complaints about the election, he said he shared their frustration with the result, but there was simply nothing he could have done. At the same time, Kemp’s willingness to pick fights with liberals, Biden, public-health experts, and “woke” corporations helped him stay on the good side of the Republican base. “A lot of people were misinformed, quite honestly, about the role I had, versus the role they thought I had,” Kemp tells me. “And so in the primary, I was able to educate a lot of people about that, and also the actions that we took to address the issues that we had, doing it in the right way.”

As defenses of democracy go, it’s hardly a clarion call. Kemp has not distanced himself from the GOP nominee for lieutenant governor, Burt Jones, who petitioned to delay certifying the election and allegedly signed on to be a “fake elector” in a scheme that is now under grand-jury investigation. “I give Kemp credit for doing the right thing, but that’s such a low bar,” says the anti-Trump conservative Sarah Longwell, executive director of the Republican Accountability Project, which works to defeat anti-democracy Republicans—and has stayed out of Kemp’s race. “We should expect our elected officials, at a bare minimum, to engage in the peaceful transfer of power, respect the will of the people, and certify the results of free and fair elections. But there were many other people who didn’t hit even that bare minimum. There was pressure to do the wrong thing, and the pressure was real.”

Raffensperger, who also survived a Trump-backed primary challenge and is seeking re-election this year, has been traveling around the state, giving a 15-minute presentation to any local group that will have him—Rotary Clubs and chambers of commerce, tea party groups and local GOP chapters—that patiently and factually knocks down each of the well-worn conspiracy theories about 2020. “We’ve been pushing back against election deniers on both sides of the aisle, just making sure that people understand that we have fair and honest elections,” he tells me. It’s a gradual process, but he believes it is working. Most rank-and-file voters are simply not as passionate as Trump about the 2020 election, and Raffensperger believes their delusions represent a larger frustration with government and the economy. “I think when we get government with a focus on solutions that work for everyone,” he says, “then a lot of this will dissipate.”

If Kemp wins re-election, he will have proven that Republicans can keep Trump’s voters in the tent without indulging his dangerous conspiracism. “Kemp has effectively charted a new path for Republicans to compete in states where you need to turn out a deep red base to win without alienating suburban swing voters,” says Brad Alexander, an Atlanta-based lobbyist and Kemp ally. “Paradoxically, all the incoming fire he didn’t respond to during the COVID shutdown debate and his primary challenge from Perdue has accrued significantly to his benefit in the general election.”

Kemp steadfastly refuses to engage with questions about 2024—Trump’s potential candidacy, his own ambitions, others who may throw their hat in the ring, what his race says about a future GOP playbook. “Anybody that is focused on 2024 right now, they are doing a disservice to us winning the midterm election,” he says. “They’re being selfish.” Besides, he points out, the current playbook still has to be proven. “You’re not going to be asking me those questions if we don’t win,” he says. “You’ll be asking somebody else, ‘How’d you do it?’”

A few hours after Kemp’s visit to the Kia plant, his opponent takes the stage in a South Atlanta parking lot full of Black bikers. Behind Abrams, the DJ spins a track by the local rapper Pastor Troy, who has refashioned his exuberant Atlanta Falcons theme song, “No Mo Play in G.A.,” into a political anthem. “If we/ All vote/ No one can save Kemp,” he raps. “That’s why/ My vote/ For Stacey Abrams.”

“This is about unfinished business,” Abrams proclaims. “Four years ago, I told you what I thought would happen. Now I’m here to tell you what didn’t happen, but how we can make it right.” If elected, she promises to expand Medicaid, protect abortion rights, and spend the state’s budgetary surplus on housing and services rather than tax cuts.

“We don’t have an enthusiasm gap, we have a trust gap,” Abrams says. “I just need you to trust me one more time, to look at my record and know that what I say I’m going to do I’m going to do. When I didn’t get the job when I applied four years ago—and I’m not confused, I know I didn’t get the job—I looked at what I put on my application and what I said I would work on.” Over the last four years, she says, she’s been fighting for democracy and fairness for all Georgians.

Many Democrats credit Abrams for the state’s blue turn. Her political operation, which registered and turned out hundreds of thousands of new voters in 2018, never let up after that, helping power 2020’s Democratic victories. A fundraising powerhouse, her 2022 gubernatorial campaign is on track to nearly double Kemp’s spending. Yet national Democrats are increasingly pessimistic about Abrams’s chances. She has been touring the state targeting Black male voters in particular, a group with which her support has notably eroded. Some local Democrats privately grumble that her outreach has been insufficient and that her national celebrity has turned off practical-minded voters.

Read More: Stacey Abrams Has a Plan to Turn Georgia Blue.

But it seems more likely that Abrams is losing not because of anything she’s done wrong, but because of what Kemp’s done right. In our interview, Kemp tells me that minority and working-class voters especially appreciated his keeping the state open during COVID. “I think the pandemic really has opened a lot of people’s eyes,” he tells me. “Traditional, diehard Democratic voters have made the decision, you know what, when I have leaders that are determining whether I need to take a vaccine, or whether my kids can attend school or not, or whether I go to work—it got a lot of people to really open their eyes.”

Kemp has also named a diverse slate of appointees to state posts, from the courts to the Cabinet to state boards and commissions. He has taken criticism from some Republicans for appointing Black Democrats as judges and district attorneys in heavily Black areas of the state. An Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll last month had Kemp winning 10% of Black voters, with another 10% undecided, as well as nearly a third of other nonwhites.

“There’s just a whole different image perception out there, especially from non-traditional Republican voters, minority voters,” Kemp says. He points to his response to the February 2020 murder of unarmed Black jogger Ahmaud Arbery, which he denounced as “vigilantism” and called on the Georgia Bureau of Investigation (GBI) to investigate after a video of the incident was released that May. “Justice was served there because I weighed in,” he says. “GBI went in there and took charge down there and really got the facts out there and got things moving in the right way.”

Kemp, like Abrams, sees their rematch as unfinished business. But whereas 2018 was a “base turnout election,” with both sides seeking to rally their strongest supporters to the polls, this time he’s aiming at the middle of the electorate. This time, he’s aiming to prove that solid conservative governance can move the Republican Party past Trump, and win back a diverse purple state.

“President Trump and his policies brought a lot of good things to our country, and they brought a lot of good people to our side,” Kemp tells me. “Of course, there’s a lot of people that we didn’t get in the last election, and we’ve learned from that too. And what we’re doing now is making sure that we have a message that can bring a big tent to what we’re doing here in Georgia.”

With reporting by Leslie Dickstein and Julia Zorthian

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Molly Ball/LaGrange, Ga. at molly.ball@time.com