My first book, The Four, started out as a love letter to Big Tech. I was enamored of their products, their innovation, their financial success, and the future they promised. But as I got further into the research, I saw how much peril lurked in that promise. The resulting critique was not something I would have expected to write just a few years earlier. Now, half a decade later, the fault lines I recognized in Big Tech are cracking wide across society. My most recent book, Adrift: America in 100 Charts, tells that story.

As I acknowledge in the book, I’m sometimes criticized for focusing on the problems of tech or business or society, and not proposing solutions. Well, guilty as charged, I suppose. But let me say two things.

First, these problems flow in part from failures of perception and awareness. My cohort of economically successful people vastly overestimates our own contribution to our success. Society has been telling us that our nice homes and fancy cars must mean we’re hard-working geniuses, and why should we argue the point? The flip side is also true. Society tells those who’ve been dealt a bad hand, who’ve never caught a break, that their failure must come from a lack of grit, an incapacity to dream big. I believe that just pulling the veil of hype that’s been laid across our unequal society is part of the solution to that inequality.

More from TIME

While there are bad apples, in my experience people are mostly good, and they want to do right by their society. We’re more often wrong than bad, but the result is the same. America is a country of great wealth and achievement, yet a chronic illness can bankrupt a family. So my aim is to reset our assessment of what got us here, with the hope that a clearer perspective can help alter where we’re headed.

Second, to be blunt, things are really fucking bad. The dashboard of threats, from inflated asset values to irreversible climate change to armed assaults on government proceedings, is flashing red and getting worse. If I spent my entire public life pointing out the risks we face, I would never run out of material.

That said, there is also a lot that is going right, and a lot that is promising, and my critics have a point. In his first inaugural address, President Clinton famously said, “There is nothing wrong with America that cannot be cured by what is right with America.” Those are words that would have fit Reagan’s the first inaugural celebrating the “business of America,” they would have suited Lincoln speaking to a broken union, or sounded right from FDR during the Depression. They are words I deeply believe in today.

Moreover, it matters that we “cure” America. That belief is implicit in all my work, including my most recent book, but I want to make it explicit here. Although it’s out of fashion, I remain an American Exceptionalist. This country really is different, in ways that make it, in words used by presidents too numerous to list, “a city on a hill,” a beacon for the optimistic and the innovative. That’s not to say I think America is perfect—my book is called “Adrift” after all—but as a nation born not of ethnicity or dynastic conquest but rather built on the foundation of an ideal, it holds a special promise. It remains a promise unfulfilled, but one I believe is within our grasp.

The central thesis of Adrift, and the north star of my politics, is that we’ve gotten closest to realizing our ideals when we’ve balanced ruthless capitalism with the ballast of a strong middle class. We’ve drifted off that course. Here are five recommendations to help us find it again.

Simplify the Tax Code

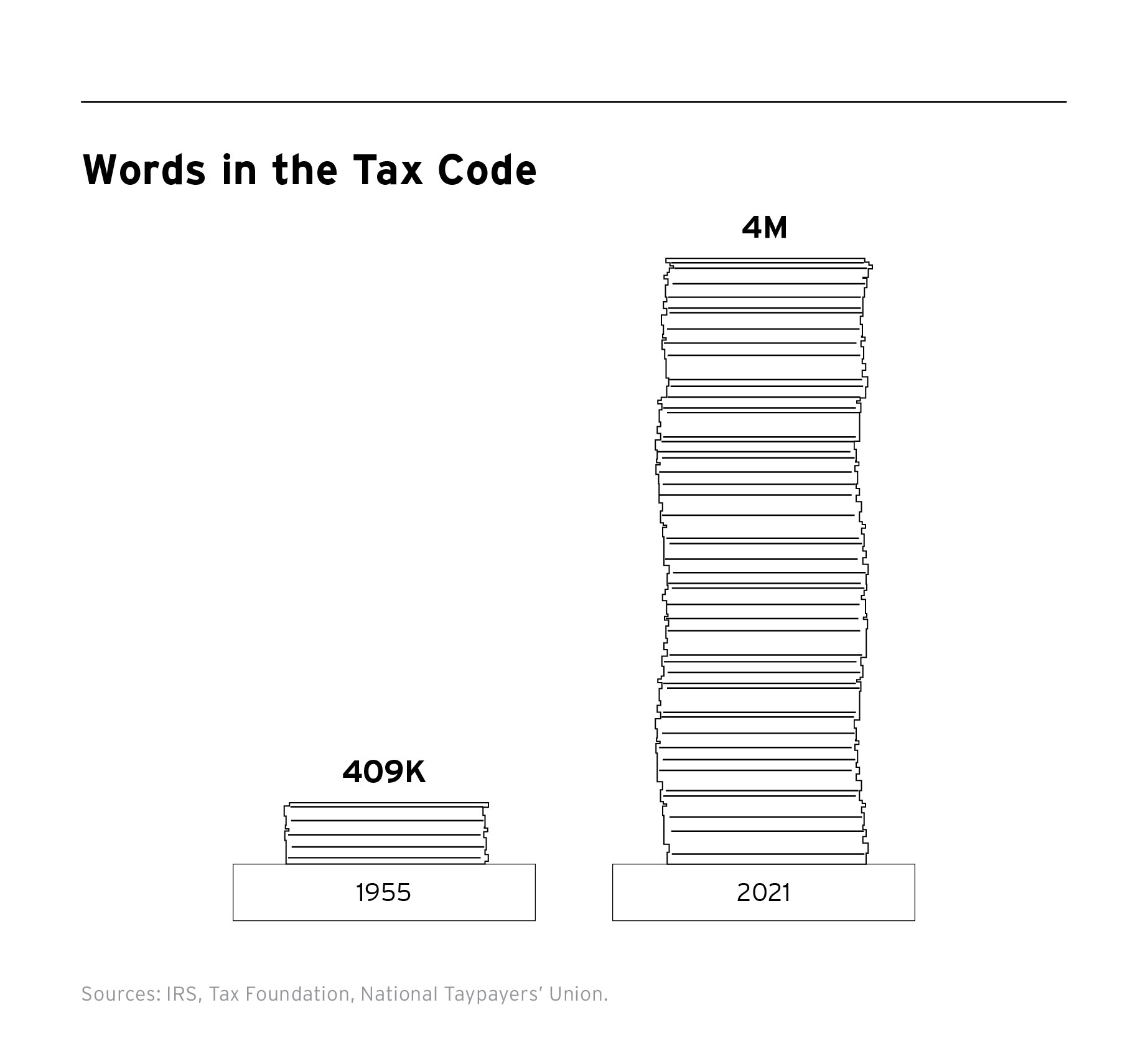

The idea of simplifying the tax system might be the only policy that all Americans universally support. Yet the tax code only gets more and more complex. In 1955, the Internal Revenue Code stood at 409,000 words; today it has roughly 4 million.

The complexity of the code is, in and of itself, a tax on the poor. The wealthy employ small militias to conquer the system and minimize their taxes. The dodges that benefit the wealthy are unavailable to everyday Americans, as is the high-priced advice necessary to take advantage of them. What this complexity means for regular people is a huge loss of time. In 2012, the IRS’s National Taxpayer Advocate estimated it took a total 6.1 billion hours for all taxpayers to handle their taxes. Compare that to the filer’s experience in thirty-six countries, including Germany, Japan, Norway, and Sweden, where the government calculates taxes and provides taxpayers with a pre-filled return.

We should revise the tax code with uniform definitions and eliminate itemized deductions in favor of higher standard deductions for households. Tax savings programs from Roth IRAs to Coverdell education savings accounts should also be consolidated to achieve one simple goal: encouraging personal savings by avoiding double taxation of them. And we should end the favorable tax treatment given to income earned by the sale of assets. Money (and the money it makes) is not more noble than sweat.

Reform Section 230

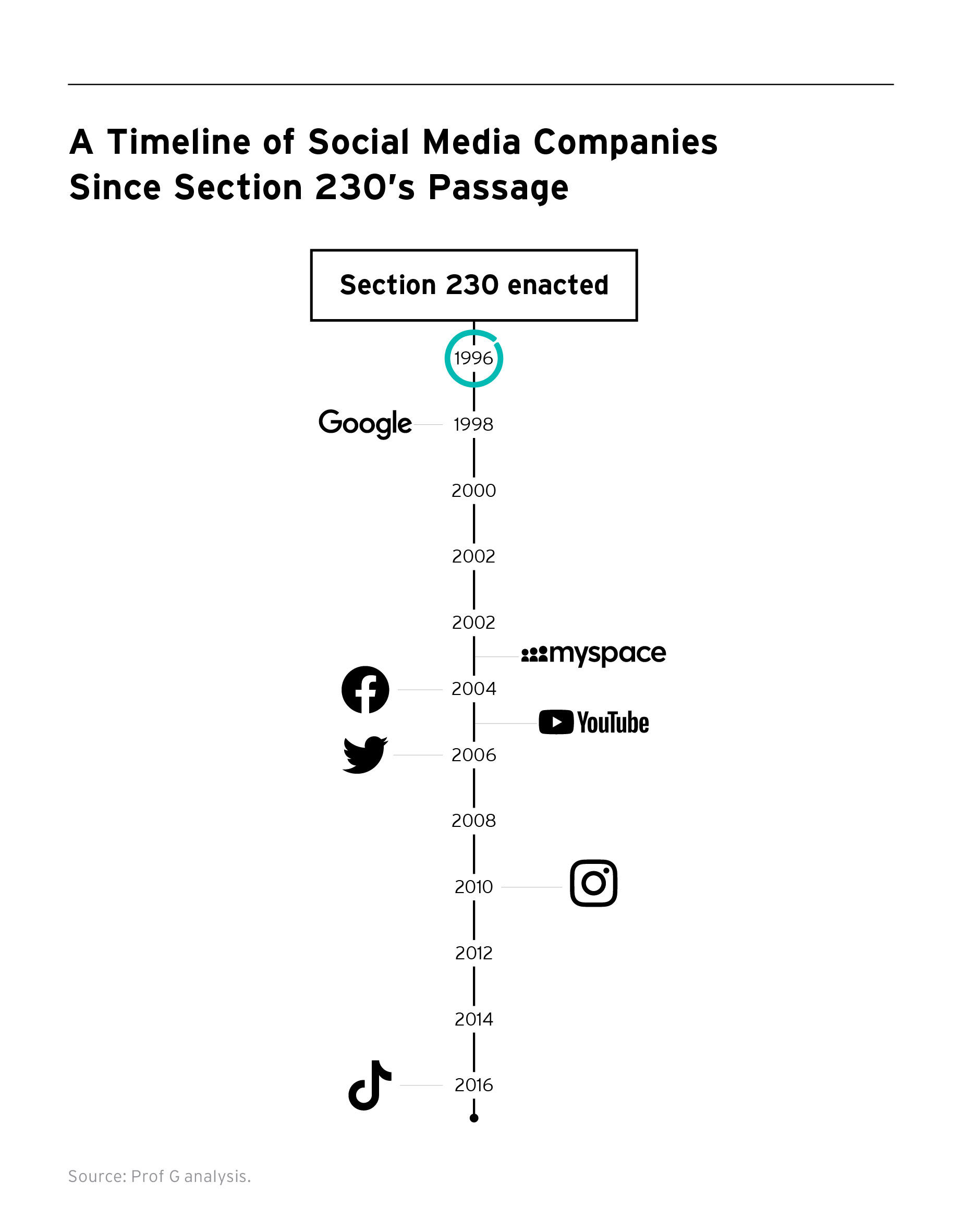

Social media companies have largely been immunized from scrutiny because of a law that was passed in 1996—when just 16% of Americans had access to the internet via a computer tethered to a phone cord.

Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube didn’t yet exist, and Amazon was an online bookseller.

Today, more than half of the world’s population uses social media, and though this expansion has produced enormous stakeholder value, the externalities have grown faster than the revenue. Social media users are exposed to algorithms of enragement—fostering an ecosystem of contempt, partisanship, and polarization. Our teens are depressed and suffering from device addiction.

Social media companies no longer need special treatment. They now have the resources and reach to play by the same rules as every other media company—rules that make the penalty and likelihood of being caught greater than the upside of ransacking democracy. These rules justly shift the cost of externalities from the commonwealth to the companies that create them.

Rethink the Land of the Free Incarcerated

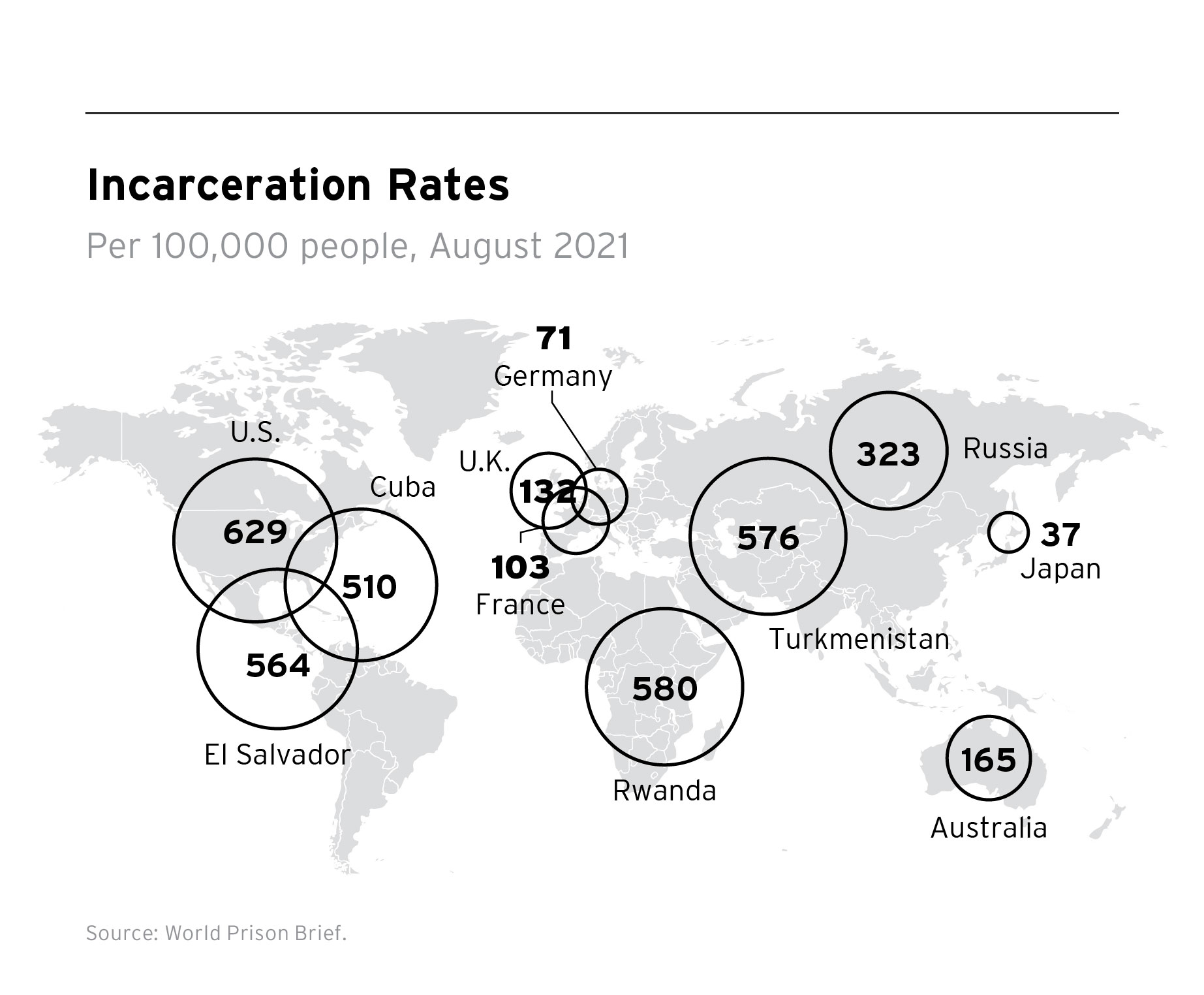

The U.S. leads the world in many things that elicit pride, but incarceration is not one of them. As of 2021, 629 out of every 100,000 Americans were behind bars, the highest rate of incarceration of any country in the world. Cuba, an authoritarian regime that imprisons people for “pre-criminal social dangerousness,” has a lower percentage of its people in jails. America’s incarceration rate is twice as high as Russia’s, not to mention seventeen times higher than Japan’s. If the U.S. prison population were a city, it would be the fifth-largest in the nation—more populated than Atlanta, Miami, Cincinnati, and Memphis combined. Black and Hispanic people make up almost 60% of the prison population, despite accounting for roughly a third of the U.S. population. And all those prisons cost more than $80 billion per year to maintain.

We must rethink this. Sentencing for nonviolent offenses should be re-evaluated, and prisoners with no history of violence should be considered for release. Drug courts, diversion programs, and other alternatives to prison should be expanded. Prison release should be accompanied by re-entry programs and education. Locking a young man away for a youthful mistake that harmed nobody and then dumping him on the street without any preparation years later merely compounds the problem. We broke criminal justice, and we need to fix it.

Enact a One-Time Wealth Tax

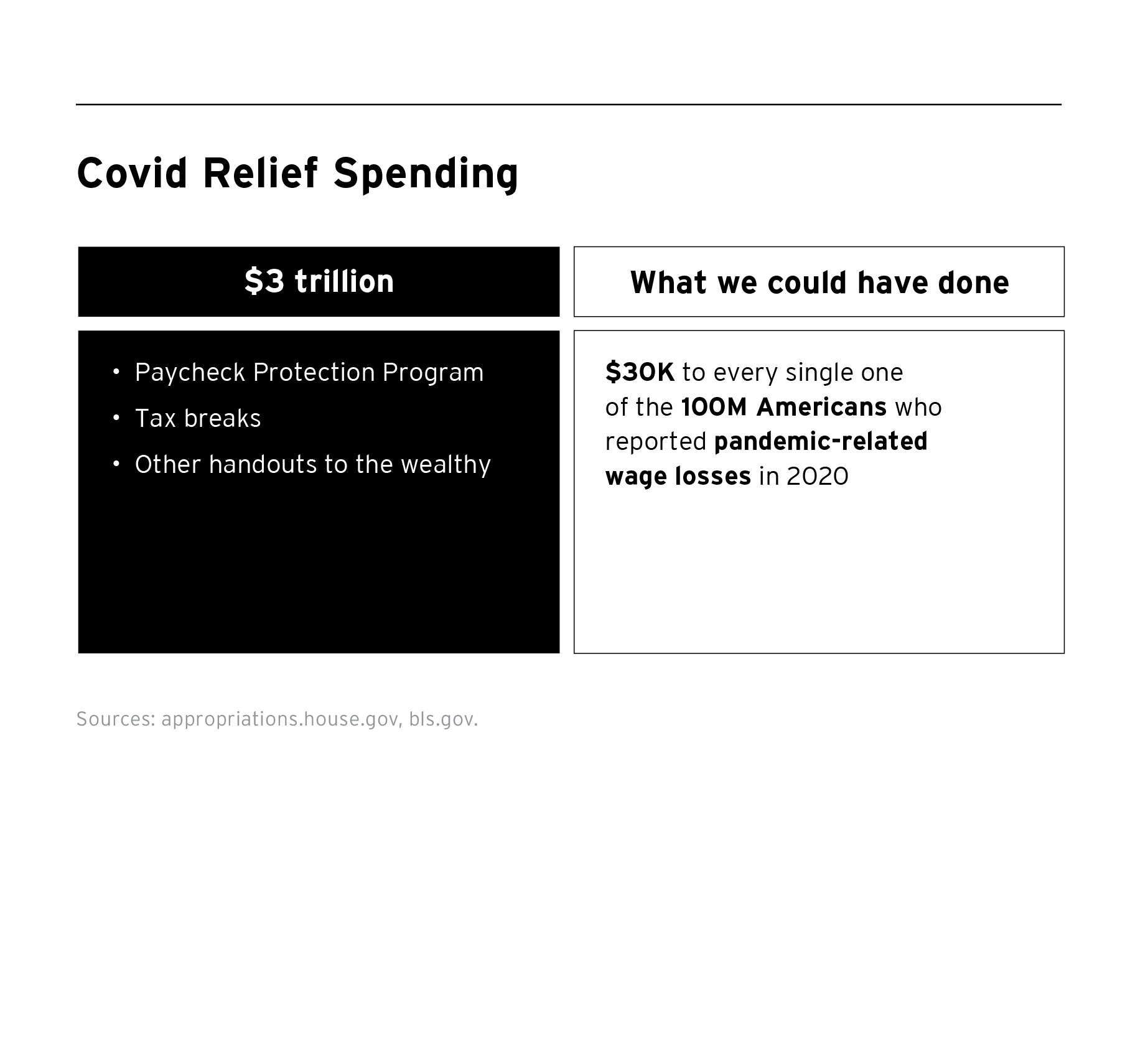

One of the largest transfers of wealth from the young to the old in U.S. history came with the government response to the Covid pandemic. It issued a massive $5 trillion in stimulus, and essentially $3 trillion ended up in the hands of the wrong people. That amount could have been

$30,000 for every American who reported pandemic wage losses. Huge swaths of America suffered, while the rich got richer.

That $30,000 in the hands of those who needed it the most would have gone much further toward repairing the economy, as more money would have ended up in the economy rather than in the markets. And who better to determine which businesses deserve to survive and are prepared for a new economy than consumers?

In the future, stimulus packages should be limited to supporting people who are food and housing insecure—not Delta Air Lines or your neighbor who owns seven dry cleaners.

But since we’re already $3 trillion in the hole, we need to recover some of those losses. We should impose a one-time wealth tax. A 2% tax on the richest 5% of households would raise up to $1 trillion. (The initial stock market bump triggered by the CARES Act’s passage helped the richest American stock owners accrue an additional $2 trillion.)

If we don’t align financial rewards and penalties with the health of our commonwealth and its citizenry, we are doomed to a pattern of failed responses to crises.

Rebrand Nuclear

Nuclear energy suffers from a tragic branding problem. The technology is a carbon-free and reliable source of twenty-four-hour-per-day power. A single generator produces enough electricity to run all the homes in Philadelphia. And nuclear power has been in wide use around the world for generations.

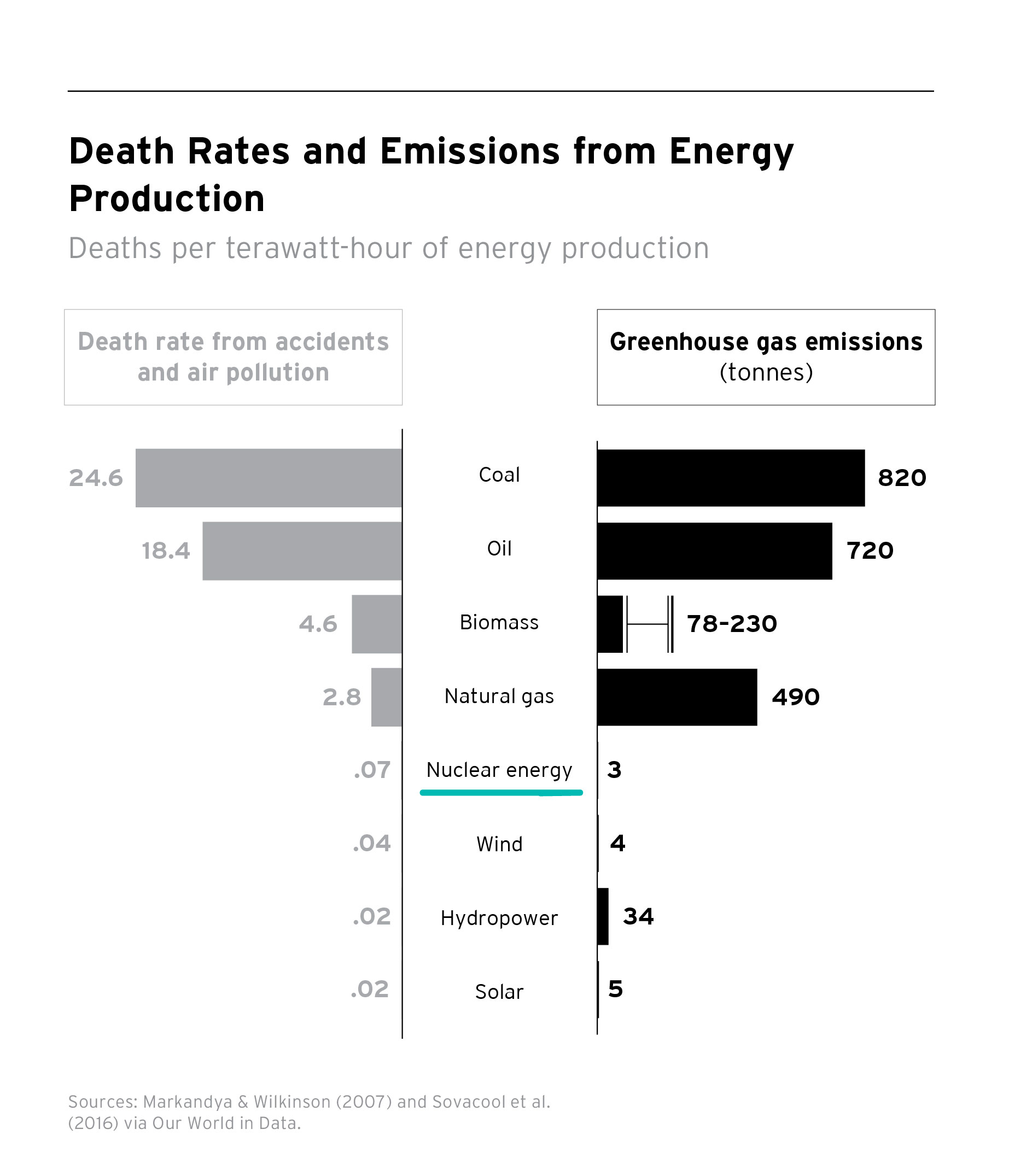

Yet only 29% of Americans view it favorably, and 49% view it unfavorably, making it the most unpopular energy source after coal. Our apprehension toward this powerful clean energy source stems from isolated, highly infrequent incidents. In reality, nuclear power is one of the safest energy sources in the world, registering accident- and pollution-related death rates roughly 300 times lower than those of coal and oil, relative to their energy production.

It’s time for a rebrand.

Adapted from Galloway’s new book, Adrift: America in 100 Charts published by Portfolio/Penguin

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com