Warning: This post contains spoilers for Don’t Worry Darling

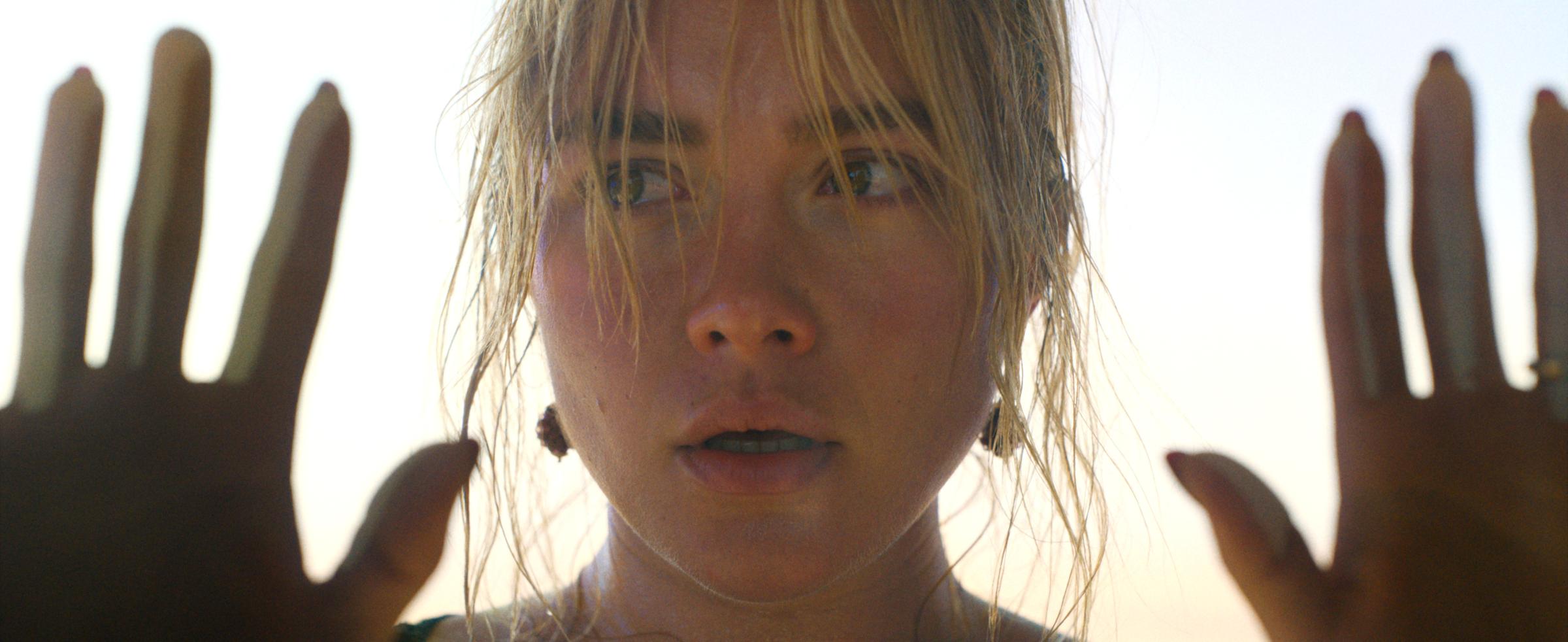

Early in Don’t Worry Darling, which drops on HBO Max Nov. 7, our hero Alice (Florence Pugh) begins to suspect that something is amiss. Alice and her handsome husband Jack (Harry Styles) are the picture-perfect protagonists of Olivia Wilde’s controversial and highly-anticipated follow-up to Booksmart, her directorial debut. They live in a 1950s-era Palm Springs-esque desert suburb dotted with tidy midcentury modern homes. They’re young and deeply in love, one of a number of couples who live an enviable life filled with poolside cocktail parties.

A cultish figure named Frank (Chris Pine) holds sway over the company town, which he has named Victory. Frank’s underlings are forbidden from sharing any information about their jobs with their spouses or families. Every day the husbands seemingly drive off to a bunker in the desert where they work on a super-secret project while their partners stay home to clean, cook, shop, and gossip.

The audience may find it odd that all these perfectly coiffed wives emerge from their houses onto their shared cul-de-sac at the exact same time every morning to send their husbands off to work. But Alice doesn’t catch on to the greater mystery of the movie until she cracks a carton’s worth of eggs and finds them missing their yolks.

Read More: Don’t Worry Darling Is Imperfect, But Not Nearly as Bad as Its Detractors-in-Advance Might Hope

She wanders into the desert, sees the bunker where the men work, and investigates. Over the course of the film, Alice argues with a series of men who dismiss her concerns as fits of womanly hysteria.

You might be here because you’re curious about the drama surrounding the movie, which has at times overshadowed the film itself. Maybe you’ve noticed that the marketing surrounding the movie hints at a big twist. Or maybe you saw saw the film and want to dig in deeper into what it all means.

Here’s everything you need to know about the ending of Don’t Worry Darling.

What happens in the movie?

Alice suspects something weird is going on with her husband Jack and their Stepford Wives existence. The wives are forbidden from going into the desert that surrounds the town. They occasionally whisper about what it is their husbands are actually doing all day and theorize about the strange sonic booms that disturb their leisurely afternoons. The fact that the town is dubbed “Victory” suggests that the men are working on a Manhattan Project-adjacent nuclear weapon or something similar.

Things go sideways when one of Alice’s friends, Margaret (KiKi Layne), wanders into the desert after her child and claims she saw something terrible there. The company tells the town that the son died in the desert, further reinforcing the idea that wandering off is dangerous. But Margaret says the company took away her son as punishment for uncovering whatever mystery she found. Margaret then slices her throat open in front of Alice, seemingly killing herself, though a doctor tells Alice that Margaret recovered. We never see Margaret again.

Read More: If Olivia Wilde Were a Man

Around this time, Alice sees a plane crash in the desert and wanders into forbidden territory to find it. Instead, she finds the bunker where all the men work. She approaches the building and, when she touches it, sees a bunch of trippy images, including black-and-white dream-like sequences of Busby Berkeley-style dancers. (These women are performing for men, if that imagery wasn’t obvious enough.)

She reawakens in bed and spends the rest of the movie trying to unravel the mystery. In a series of increasingly desperate episodes, she confronts her husband, her neighbor and confidante Bunny (Wilde), and Frank. After a crackling dinner party showdown, Frank all but admits to Alice that he’s manipulating the people of Victory. But he departs the party before Alice can finish her line of questioning, leaving Alice to argue with the spineless Jack. Jack pretends he is going to run away with Alice but instead sets her up to be kidnapped by a group of men and bemoans his own bad fortune as she’s dragged away. The goons try to reprogram her through electroshock therapy.

What’s the twist?

It’s all a simulation!

The electroshock therapy doesn’t go as planned. While lying on the table, Alice accesses memories of her real life.

It turns out that she is, in reality, a doctor, not a housewife. She lives in a dreary city apartment and works terrible hours. Jack is her partner in that universe too. He doesn’t particularly like how much Alice works or that she’s the breadwinner in their relationship. The movie attempts to up Jack’s creep-factor in these scenes by giving Harry Styles very un-Harry Styles-like hair and clothes.

While listening to a creepy podcast with men’s rights activist vibes, Jack hears about special VR technology invented by Frank that allows a man and the woman of his choosing to be plugged into a ’50s-style universe. The woman, it should be noted, doesn’t consent to the virtual reality experience. Nor is she even necessarily the man’s partner—she can be just some random woman that the man presumably…kidnaps? Yikes. Jack signs up himself and Alice, without Alice’s consent.

When Alice returns “home”—well, to her 1950s simulation home—she flinches as she kisses Jack, and more real-world recollections flood in. She confronts Jack, and he explains that he made this choice because she was miserable in the outside world working long hours in a hospital. Now she just gets to relax by the pool. He wishes that he never had to leave the simulation himself, but he does so he can go to a job in the outside world every day and fund his creepy daydream.

Alice screams that she chose her so-called miserable life, and that she enjoyed it. That’s the tricky thing about the patriarchy: It often disguises itself as domestic bliss.

Alice then accidentally kills Jack. Alice’s neighbor Bunny shows up and reveals that she knows they’re living in a simulation. Bunny is there voluntarily because she lost her children in real life and she gets to see her fake children in virtual reality. (A strange revelation considering that all the messiness and joy of children seems to be sapped from Bunny’s offspring. They are mere automatons.)

Bunny also mentions that if you kill a man in virtual reality he dies on the outside. (Why? Don’t think about it too much). Alice doesn’t seem all that sad about murdering her controlling loser of a husband. Bunny, a font of crucial information, tells Alice to run to the bunker in the desert. It’s the only means of escaping the simulation. Again, why? Perhaps because Wilde wanted to film a cool chase scene with old-school cars. Alice just barely makes it. The end.

Read More: The 52 Most Anticipated Movies of Fall 2022

Okay, so what was with that plane?

Alice watching a plane crash kicks off the entire adventure. Was it a glitch in the VR experience? It’s hard to imagine that Frank would purposefully program that into the simulation.

What about that moment when Alice almost gets crushed to death while cleaning?

Alice has several trippy experiences, like the wall of her house nearly crushing her to death and the dance class hallucination. Is that a glitch or Frank messing with her head as some sort of punishment? It’s never made clear.

Can women die in the simulation?

Apparently not. Bunny specifically says that if men die in virtual reality they die in real life. Why would women be the exception? Unclear.

Margaret slashes her throat early in the film and disappears. She either died by suicide in real life or found that killing herself was the only way to escape the simulation.

How does Alice eat or go to the bathroom while using the simulator?

Even if Alice’s safety isn’t threatened inside the simulation, how is she surviving outside of it?

We see Alice hooked up to the simulator machine in a bed. Didn’t any of her coworkers or family ask about her going missing? Once she’s attached to the machine in the bed, how does she eat? And how does she go to the bathroom? Does Jack have to take care of that? That would seem to zap a lot of the “romance” (and the quotation marks are doing a lot of work there) from Jack’s fantasy with Alice in dream land.

Why did Frank’s wife stab Frank?

The status of Frank’s wife Shelley (Gemma Chan) throughout the movie is a mystery. Does she know that she’s living in a simulation like Bunny? Or did Frank trick her? Presumably the latter: He figured out how to capture his wife in his 1950s suburbia and then podcasted about it to other insecure men across the world.

At the end of the movie, when Alice is making her escape, Frank is talking on the phone with his in-virtual-reality security about how to stop Alice. Shelley casually walks over and slips a knife into Frank. Why does she do this now? Did she just figure out what Frank was up to? How did she solve the mystery, since Frank remains opaque on his phone call? Did other clues like Margaret slitting her own throat or Alice confronting Frank at a dinner party not tip her off previously?

Shelley also makes a comment about how it’s now “her turn.” Her turn to run the simulation? Is she going to help women entrap men there? Change the simulation? Escape? We will never know because we never see her again.

Why did Harry Styles dance at that company party?

There is a scene in the middle of the movie when Frank promotes Jack, and then Jack does a really long, elaborate dance onstage at a party while Alice has a breakdown in the bathroom. I have absolutely no explanation for why this scene exists in the movie. Maybe there’s a Dance Dance Revolution mini-game within this virtual reality universe.

Jack’s dance does inspire the men of Victory to start chanting about how they’re creating the future in a manner that’s reminiscent of Nazi rallies.

What are the influences on Don’t Worry Darling?

The most obvious touchstone for Don’t Worry Darling is The Stepford Wives. For the uninitiated, Stepford Wives is a horror novel-turned-movie (released in 1975, followed by a 2004 adaptation with Nicole Kidman) that satirizes men’s reactions to women’s liberation. It centers on a photographer named Joanna who moves with her husband to an eerily perfect town. All the housewives are vapid, strangely devoted to housework, and subservient to their husbands.

Joanna investigates her suspicions that something is amiss in the town while her husband spends an increasing amount of time at the men’s club. Joanna finds out that the women in the town used to have thriving careers but became docile housewives with notably larger breasts and no remaining interest in their previous jobs. She eventually discovers the men are transforming the women into, essentially, sex robots. She is betrayed by her own husband and turned into one herself.

There’s a moment in the Stepford Wives book in which Joanna briefly returns to the city. She observes the working women on the streets and describes them “rushed, sloppy, irritated—and alive.” That line beautifully illustrates the contrast between Alice’s real life as a doctor (alive) and her imagined one as a housewife (in a trance).

Wilde has also cited Betty Friedan’s earth-shattering book, The Feminine Mystique, which chronicled the dissatisfaction of the American housewife and helped launch second-wave feminism in the U.S., as an influence.

The visuals borrow heavily from 1960s films like the Sean Connery James Bond movies, but also (more recently) from Mad Men. The stifling midcentury marriage between Alice and Jack recalls that of Revolutionary Road. Alice’s realization that she is being gaslit and her eventual escape echoes the finale of Get Out. Alice’s name may be a nod to the Alice who falls down the rabbit hole into a topsy-turvy world in Alice in Wonderland. The simulation plot recollects films like The Truman Show and Pleasantville.

What does Don’t Worry Darling have to do with The Matrix?

The Matrix is a touchstone, not only because the entire plot of that movie centers on the hero deciding to unplug from a beautiful-looking but unreal simulation in favor of a grittier life in reality, but also because of The Matrix’s inadvertent influence on the language of men’s rights activists.

In The Matrix, the hero Neo (Keanu Reeves) must choose between a blue pill to continue his delusion or a red pill to wake up to reality. In certain corners of the Internet, dissatisfied men use the term “red pill” to refer to the moment they “realized” that women allegedly run the world. Red Pill forums on the Internet have become a place where mostly white, mostly straight men air misogynistic views on women and bemoan their diminishing status in society. (The creators of The Matrix, Lana and Lilly Wachowski, both trans women, have since explained that The Matrix is actually an allegory for coming out as trans, to the consternation of many men’s rights activists.)

Wilde has specifically cited these dark corners of the Internet as inspiration for the villains of the film. One can easily imagine Jack identifying himself as someone who was “red pilled” when he felt emasculated by his wife’s earning potential. He sought refuge among a community of men yearning for a time when men controlled women’s bodies and behavior. Ironically, in Wilde’s movie, these red-pilled men purposefully delude themselves in order to gain back power instead of living in reality.

What do incels, men’s rights activists, and Jordan Peterson have to do with the plot?

A lot! The main antagonists of Don’t Worry Darling are insecure men who want to control women, their careers, and their bodies. Jack doesn’t feel like he’s taking care of Alice—so he takes her as his prisoner. After hearing Frank lecture about men losing power in society and needing to prove their manliness on a podcast, Jack skulks through the rain in the middle of the night to find Frank in real life and sign up for this Victory Project.

We don’t know the motivations for the other men sticking their partners or other random women inside the simulation, but we can guess that they’re all controlling and creepy, and their sexual relationships reek of a lack of consent. These types of men will be familiar to any woman who spends time on the Internet. And there are certain figures who cultivate followings of disaffected men who, after millennia of enjoying advantages in the world, blame the advancement of women for any current ills.

Wilde told fellow director Maggie Gyllenhaal in Interview Magazine that she based Chris Pine’s character specifically on one such incendiary thinker: Jordan Peterson. Peterson has gained devotees among such men who blame advancements in gender relations for their misery. He has made a career of inflammatory statements about trans rights, gender pronouns, and gender equity.

“We based that character on this insane man, Jordan Peterson, who is this pseudo-intellectual hero to the incel community,” Wilde said. Gyllenhaal said she didn’t know the term “incel.” (Bless Gyllenhaal for not spending all her time on Twitter.) Wilde explained that it refers to “involuntarily celibate,” “basically disenfranchised, mostly white men, who believe they are entitled to sex from women.”

Wilde added: “They believe that society has now robbed them — that the idea of feminism is working against nature, and that we must be put back into the correct place.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliana Dockterman at eliana.dockterman@time.com