Peiter Zatko, the Twitter whistle-blower, is a black belt in jiu-jitsu. The day before his complaint against the social media company was published, Zatko was sitting in his lawyer’s office in Washington, scrolling through his camera roll to find a photo of his legs locked around someone’s neck. The move is called a side-triangle. It’s totally safe, he says, because the opponent will black out before a lack of blood flow to the brain can cause any lasting damage. One of the things Zatko likes about the martial art, he explains, is that it’s less about brute strength than finding creative ways to maneuver your opponent into a weaker position.

That talent translates to cybersecurity. In Nov. 2020, Zatko, the hacker known as “Mudge,” was hired as Twitter’s security lead, with a global remit to fix gaping vulnerabilities in one of the world’s most important communications platforms. But 14 months later, he was fired. Six months after that, he filed a sweeping whistle-blower complaint that paints a damning portrait of a company in crisis. In an 84-page complaint to federal regulatory agencies and the Department of Justice, which was first reported by the Washington Post and CNN and which TIME obtained from a congressional source, he describes Twitter as crippled by rudderless and dishonest leadership, beset by “egregious” privacy and security flaws, tainted by foreign influence, a danger to national security, and susceptible even to total collapse.

Zatko says he felt an ethical duty to come forward. “Being a public whistle-blower is the last resort, something that I would only ever do after I had exhausted all other means,” he told TIME in a lengthy interview on Aug. 22. “It is not an easy path, but I view it as continuing to help improve the place where I was employed.”

Twitter quickly hit back. Zatko was fired for “ineffective leadership and poor performance,” CEO Parag Agrawal wrote in an email to employees, calling the disclosures a “false narrative that is riddled with inconsistencies and inaccuracies” and presented out of context. “Mudge was accountable for many aspects of this work that he is now inaccurately portraying more than six months after his termination,” Agrawal said.

The story of how a top Twitter official turned whistle-blower is not a straightforward saga. In more than a dozen interviews with Zatko’s friends, family, and current and former colleagues, the portrait that emerges is more complicated. Eight current and former Twitter employees, who spoke with TIME on condition of anonymity in order to discuss issues they were not authorized to speak publicly about, said that many aspects of Zatko’s disclosures rang true to their experience, particularly his allegations of security deficiencies and shortcomings in company leadership. Some of the same sources, many of whom professed to like and admire Zatko, suggested that various allegations were misleading, overblown, or lacking context—in part because Zatko was straying into areas of the company into which he had only basic insight.

Zatko’s allegations have emerged at a pivotal moment for Twitter, which is locked in a legal battle over an agreement to sell the company to Elon Musk. That makes the accuracy and credibility of Zatko’s claims a multibillion-dollar issue, and the object of considerable debate by his former colleagues. “Is Mudge generally correct? Yes,” says one current Twitter employee who worked with Zatko. “Where he is correct is that Twitter has absolutely been negligent in creating the appropriate security infrastructure for a company that has the level of impact it has … Is Mudge wrong about lots of things? Also yes. I think there’s a lot of sour grapes.”

Zatko had come from a long line of jobs where he had free rein to tear up organizational structures and prioritize security above all else. But at Twitter, current and former colleagues say, he found himself in a different environment: navigating tense internal politics at a corporation bent on boosting revenue, without support from his superiors. Some employees caught up in the tumult perceived Zatko to be a figure hired by then CEO Jack Dorsey for publicity reasons, stepping on the toes of qualified colleagues with more institutional knowledge. Technically brilliant and morally rigid, Zatko was an iconoclast stepping into a corporate bureaucracy. “It’s like asking a doctor who’s been trained to do brain surgery to suddenly become a podiatrist,” says a former Twitter colleague.

The polarized reactions to Zatko’s disclosures illustrate just how atypical a tech whistle-blower he is. Last year, Frances Haugen, a former Facebook product manager, disclosed tens of thousands of pages of internal company documents that revealed a company prioritizing profits over user safety. But readers didn’t have to take Haugen’s word for it; they could read the words of Facebook’s own safety teams. Zatko is different. As a former senior executive, he had a bird’s-eye view into Twitter’s decisionmaking, ultimately responsible for hundreds of staff in some of Twitter’s most high-priority work streams. But he didn’t release the same breadth of documentation as Haugen; while Zatko supplied some exhibits to support his claims, including internal emails, his partially redacted disclosures rely largely on his own credibility as one of the most celebrated figures in cybersecurity. He is implicitly asking the public to trust that his version of events is the correct one, and that Twitter is lying.

Zatko may lose money by coming forward. Half of his compensation at Twitter was in cash, but the rest came in stock, says John Tye of the legal non-profit, Whistleblower Aid, which is representing Zatko. The value of those shares dropped by about 9% when news of Zatko’s allegations broke. Tye insists Zatko’s motivations are rooted in a desire to see the company succeed in the long term, not his own financial self-interest.

The fate of Twitter’s stock price may be just the first of a cascading series of consequences from Zatko’s disclosures. His contention that Twitter has a bigger bot problem than executives admit may prevent them from forcing completion of the Musk deal. Tye says that his client prefers Twitter to remain a public company, for the public good. “We have concerns if the SEC were to lose jurisdiction if the company goes private, because there’s one less law-enforcement lever,” Tye says. “That’s a problem for accountability.” Zatko told TIME he has never met Musk and did not provide any information to him in advance of his disclosures becoming public knowledge.

Zatko’s allegations could ripple out even further, in Washington and beyond. On Sept. 13, he is set to testify in Congress about the allegations, which could spur investigations by the SEC and FTC. That could in turn further erode public faith in social media companies generally, as they face escalating questions about their influence on politics and society, as well as global efforts to rein them in. All of which means the question of what kind of whistle-blower Peiter “Mudge” Zatko is has consequences well beyond Twitter’s future.

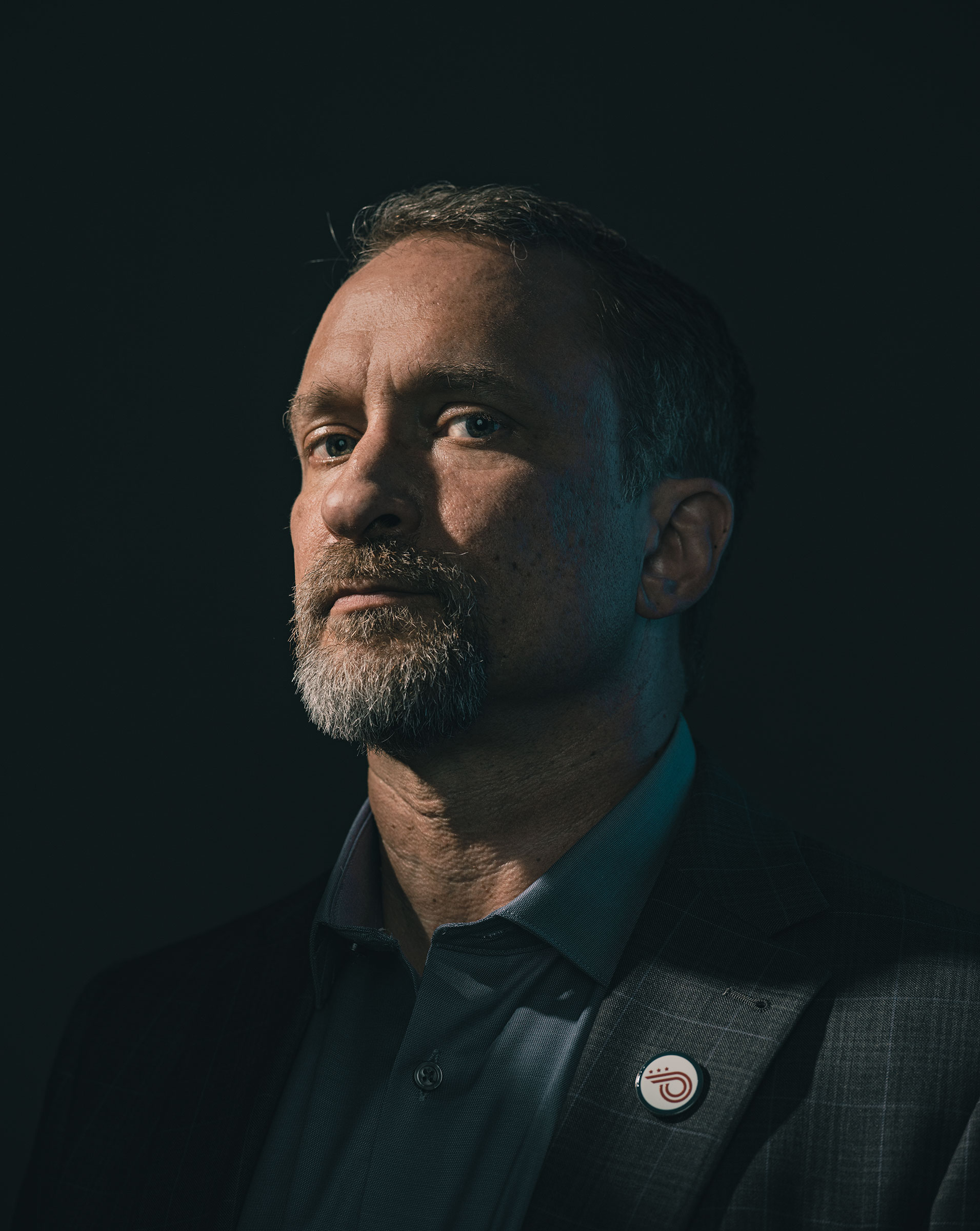

In his Twitter profile picture, Zatko has flowing, shoulder-length brown hair, with a ring of light hovering above his head like a halo. But it’s been more than two decades since he traded this long-haired look—“hacker Jesus,” his wife Sarah Zatko jokes—for a clean-cut mien befitting a man who’s done tours at the highest levels of government. As Zatko sat down for his interview with TIME on the eve of the allegations becoming public, he sported a crisp goatee flecked with gray, wired spectacles, and a lapel pin depicting the logo of his lawyers, Whistleblower Aid.

The profile picture is no accident. Zatko cites his famous work in the 1990s as both the defining era of his life and the grounding for his present morality. “I always ask myself: What would the Mudge of the late ‘90s think about what I’m doing now?” he says of his decision to blow the whistle on Twitter. “I want to make sure I haven’t lost that drive, that my ethics are still just as strong, that I’m fighting for people just as hard.”

Zatko is both attuned to and skilled at nurturing the mythology surrounding him. When he was a toddler, his father hung over his crib a mobile made of circuit boards. “He wanted me not to be afraid of technology,” he said in a 2011 interview with a trade magazine. He says he began hacking at the age of 5, picking locks and reverse-engineering computer games with his dad on a late-1970s Apple II computer to get around copyright protections. As a teenager, he spent his time surfing ARPANET, the predecessor to the modern internet, along with the bulletin boards where communities of online hackers were taking shape.

Growing up in Alabama and Pennsylvania in the 1980s, his childhood heroes were the social activist Abbie Hoffman and the musician Frank Zappa. Zatko studied the guitar and the violin, and chose music over computer science, attending the Berklee College of Music in Boston. After graduating, he split his time between playing at clubs with his progressive metal band Raymaker, part-time tech-support work, and working with a high-profile hacker “think tank” called the L0pht (pronounced Loft) to expose corporate security flaws. He would soon become its most prominent member and went on to join a hacking cooperative known as the Cult of the Dead Cow.

At the L0pht, Zatko pioneered a strategy of publicly embarrassing companies that refused to patch vulnerabilities that he and his fellow hackers had flagged to them. His biggest nemesis in the 1990s was Microsoft. When Zatko and his colleagues showed it was possible to insert malicious code to run secretly on any machine, Microsoft ignored it. So the L0pht released a user-friendly tool that allowed anybody to break into Windows users’ personal accounts, reasoning that it was the only way to force the company to finally fix its vulnerabilities. It worked. Today, Zatko says, Microsoft has one of the most advanced security programs in the world.

Still, “responsible disclosure,” as the tactic of public embarrassment became known, is a bit of a misnomer. Criminals could use the hacking program he released to crack passwords in less than 24 hours, enabling them to steal credit-card or medical data from innocent users using unpatched machines. Zatko says that he thought “long and hard” before deciding that releasing the tool was the only way to make Microsoft change its ways and protect its users, even if some people got hurt in the short term.

“Dishonesty is definitely something that frustrates him,” says his wife Sarah, a former mathematician at the National Security Agency. “It doesn’t mean he’s always trying to make a big public fuss, because if you can get things fixed … through proper channels it’s always easier on everybody. But if that’s not possible, there’s always this fallback.”

Zatko and other members of the L0pht agreed to testify about internet security on Capitol Hill in May 1998. In the congressional hearing room, they were identified on their placards only by their hacker names. Zatko sat in the center of the group of seven hackers and did most of the talking. Even then, he flashed a flair for the dramatic, getting lawmakers’ attention by infamously claiming he could take down the internet in 30 minutes. “How can we be expected to protect the system and the network,” Zatko asked the assembled Senators, “when all of the seven individuals seated before you can tear down the foundation that the network was built upon?”

Still in his 20s, he began to work as an unofficial adviser on internet-security issues to Richard Clarke, who would become the cybersecurity czar for three different U.S. Presidents. A photo from 2000 shows Zatko at the first White House meeting on cybersecurity, talking to then President Bill Clinton.

After the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, cybersecurity suddenly became an urgent part of counterterrorism strategy. Bad actors and “spam gangs” run out of Russia and Eastern Europe were releasing viruses and other malware, wreaking havoc on systems unprepared to counter them. Zatko began advising U.S. intelligence agencies and the military for free.

Zatko was shaken by what he uncovered when he started digging. “I started to figure out numerous ways of knocking the financial sector down,” he says. “It just started to dawn on me that I, as an individual actor, could wreak serious havoc. And this is shortly after 9/11.” He had a bad reaction to drugs that his psychiatrist prescribed to deal with his rising anxiety, which only made things worse. It took a long time for him to emotionally recover. “Every security professional has the moment where they have started to learn enough about the field that all of a sudden they have this existential crisis,” says Zatko’s wife Sarah. “Then you either become [nihilistic] and everything’s hopeless, or else you have to figure out a way to get past it and try to fix your corner of things.”

Out of his rut and adopting that new mindset, Zatko was tapped in 2010 to lead cybersecurity efforts at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). “I didn’t go there because I thought it was cool. I didn’t go there because I wanted to be a part of the government,” he told the audience at the DEF CON hacker conference in 2013. “I actually went there because I thought they and other parts of government had kind of lost their way, and I had an opportunity to go in and fix it.”

One of his first moves was bringing in hackers and forcing career officials at the military office to spend three days in a conference room with them, says Renee Rush, a U.S. Air Force veteran who worked with him at the agency. “Mudge could go anywhere and get a big paycheck,” Rush says, “but you’ll never find him in a job that doesn’t have a distinctive mission.”

Zatko’s sense of principle has a way of engendering loyalty among his many mentees, both inside and outside his field. Ryan Hall, a champion mixed martial artist, became close friends with Zatko after Zatko joined Hall’s gym in Arlington, Va., in 2010 to practice jiu-jitsu. He recalls seeing Zatko at a coffee shop a block from the gym, sporting jeans and a T-shirt, surrounded by men in well-cut suits. “Peiter has very little time for moral waffling,” Hall says.

After 3½ years, Zatko left DARPA for stints doing security research at Google and the payment processor Stripe. He cast both as companies that took security advice seriously. “The executives actually back security and let us do things differently (otherwise I wouldn’t be there!),” he tweeted approvingly in 2018 while at Stripe.

Over the years, internet security has grown more complicated as its impact expands beyond scams, cyberattacks, and corporate or government security hacks. Zatko publicly expressed his frustration that veteran security experts’ advice was being ignored in the lead-up to the 2016 election. The Democratic National Committee reached out to him for help to improve its network and information security, but even his most basic suggestions were considered too “annoying,” he said. “DNC creates Cybersecurity board made up of well-meaning people with no cybersecurity expertise,” he tweeted in August 2016. “Your move Russia…”

Four years later, after the Trump era showed just how essential the security of social media platforms was for safeguarding democracy, Zatko was sitting in his home office in New Jersey. The room is in an extension with no central heating or cooling system. In the winter, it is warmed by “way too many” computer cores—over 100, he estimates. It’s a messy space, with dog-eared textbooks strewn across the floor and framed letters of praise from national security luminaries on the walls. Zatko’s phone rang. On the other end was Dorsey. The man who had co-founded Twitter addressed him as Mudge, and told Zatko the hacker’s work during the 1990s was one of the reasons he pursued a tech career. “That just blew my mind,” Zatko recalls. “I’m talking to the guy who created, let’s face it, a platform that is critical worldwide. It influences governments, social change, it is the perception many people have of the world. And he was telling me that he was interested in me.”

Zatko eventually decided to accept the unorthodox job Dorsey was offering, overseeing Twitter’s entire security operations, both data and physical. Zatko saw the protection of a platform as influential as Twitter as perhaps his most effective way to “make a dent in the universe”—a personal motto originating from his time at the L0pht.

The move was hailed by experts as a sign of Twitter’s serious commitment to fixing long-standing security issues. As one security analyst put it, “A rare moment of cybersecurity sunshine where it seems the right person is put in the lead on addressing a major issue.”

Twitter needed him. The company was reeling from one of the most embarrassing incidents in its 16-year history. In July 2020, a trio that included two teenagers used extremely basic phishing methods to gain access to the accounts of Twitter employees. They were then able to send tweets from the accounts of Joe Biden, Barack Obama, Elon Musk, and a slew of other blue-checked accounts, setting up a scam that netted them over $100,000 in Bitcoin.

The incident was hardly the company’s first major security lapse. The year before, the U.S. government had accused two Twitter employees of being moles for the Saudi Arabian government. This month, one of them was found guilty in federal court. Back in 2011, the FTC had filed a complaint against Twitter for failing to protect consumer information. That complaint was supposed to result in Twitter implementing a robust security program resistant to cyberattacks. Yet the success of the July 2020 hackers showed how vulnerable the platform remained. “While Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Meta consistently put out new features to help people protect their accounts and information, Twitter’s focus seemed to be a bit stale,” says Runa Sandvik, a privacy and security researcher. “It’s unclear what Twitter was doing in that space, if anything at all.”

Zatko’s whistle-blower complaint says he expected to spend the remainder of his career working at Twitter. But it quickly became apparent that the company was “a decade behind” its competitors, he wrote in a staff memo included in the disclosures. Teams fighting bots were understaffed and overworked, he alleges, and internal security measures Twitter promised to develop in the wake of the 2011 FTC mandate had yet to be rolled out. Zatko’s complaint claims that a serious security breach was occurring at Twitter on average every week.

Read More: What the Twitter Whistle-blower Disclosure Means for Elon Musk.

On Jan. 6, 2021, Zatko was watching the Capitol insurrection unfold online and asked a Twitter engineering executive to curtail employees’ access to internal systems. He learned that too many employees had irrevocable access. One rogue engineer with the right system privileges could have sabotaged the platform, sowing misinformation and discord, Zatko alleges in his disclosure.

Zatko tried to patch these holes. He shuttered several existing security and privacy programs in favor of a new department, optimistically named Confidence. He drew up a three-year plan to improve defense efforts and measure spam bots, which he alleges were running rampant and unchecked across the platform. According to his disclosure, he was met with continual pushback at senior levels of the company, and when it came to security issues, he says, “deliberate ignorance” was the norm. Some product managers were “encouraged” to override security and privacy issues in order to release new products more quickly, his complaint alleges. Current and former Twitter employees who spoke with TIME corroborated the general sweep of Zatko’s allegations that Twitter often prioritized profit over security. “Unless you can make a compelling trade-off argument for why improved security or privacy will benefit the business more than their cost,” says one former Twitter employee, “it’s very hard to enforce change.”

Zatko’s complaint adds that his efforts to inform Twitter’s board about various security issues were met with alarm or anger, and that at least twice he was asked by executives to withhold information from the board. Twitter declined multiple requests from TIME to address specific parts of Zatko’s allegations. In his email dated Aug. 23, Agrawal said Zatko’s disclosures as a whole had many inaccuracies in them. Meanwhile, Dorsey, the man who Zatko thought would be his main ally, was increasingly absent and unfocused, Zatko’s disclosure says. A representative for Dorsey’s company, Block, did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

The situation began to come to a head in November 2021, when Dorsey resigned. His replacement was Agrawal, who had formerly been the most senior executive in charge of security issues before Zatko arrived. Tensions between the two quickly escalated. Zatko says in his disclosures that he became concerned that Agrawal was going to use the first board meeting of his tenure to diminish the severity of security issues. He wrote to Agrawal on Dec. 15, arguing that there were “numerous, and some significant, misrepresentations” in materials for an upcoming presentation, according to emails contained in the complaint.

Agrawal brushed him off, Zatko’s complaint alleges, and the next day, the documents were presented at a high-level Risk Committee board meeting. In a Jan. 4, 2022, email to Agrawal, Zatko called the documents “at worst fraudulent,” and wrote, “I was hired to achieve certain goals and to fix problems here at Twitter. In order to do that, we need to recognize the actual state of affairs at the company.”

A few days later, Agrawal wrote back to Zatko, saying that the company had launched an internal investigation into Zatko’s allegations of “fraud.” Zatko was asked for a detailed report to back up his claims, which he began to pull together. Less than two weeks later, before he was able to file the report, he was fired.

Zatko retained Whistleblower Aid on March 17, a month before Musk offered to buy Twitter. He concluded he had no choice but to blow the whistle. “Change sometimes requires, you know, kicking the hornet’s nest a little bit,” he says. “Ethically and morally, I had to pursue this.”

In interviews, current and former Twitter officials had differing perspectives on Zatko’s allegations. Several said that Zatko was right about many things, including data-management issues, chaotic leadership, and platform vulnerabilities. But some felt he mischaracterized or exaggerated certain details in the disclosure, particularly when it came to issues that he himself did not work on. “He didn’t know what was happening with the bots stuff,” says a current employee who worked with Zatko. “That did not fall under his security purview.” Zatko’s attorneys dispute this, arguing that he did in fact have insight into and authority over the bots issue as the ultimate supervisor of Twitter Services, which oversees global content moderation at scale. The disagreement can be chalked up to Twitter’s messy organizational structure, in which different arms of the company have competing claims to ownership of the bots issue.

Other parts of Zatko’s disclosures simply pit his word against Twitter’s. One of his most explosive claims is that Twitter “knowingly” hired “agents” of the Indian government. Because of access privileges afforded to many Twitter employees, Zatko says in his disclosure, these alleged agents could access sensitive user data. The hires came at a time when the Indian government was bristling at Twitter’s refusal to identify details about people using the platform to criticize the nation’s ruling party. Zatko had direct responsibility for the physical security of employees at Twitter, and would likely have been directly briefed on alleged espionage efforts. The disclosures state that Zatko has given more details about this incident to the Department of Justice and the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.

Twitter declined multiple requests from TIME to address Zatko’s claims about Indian agents on the record. One person with direct knowledge of Twitter’s internal affairs in India told TIME they had no knowledge of the supposed agent, but said they would not be surprised if the Indian government had at least tried to covertly appoint an agent to Twitter’s payroll, similar to the Saudi case.

Some of Zatko’s other claims strike experts as overstated. His disclosure argues that Twitter’s failure to own the rights to training data of machine-learning models constitutes “fraud,” for example. That shortcoming is an industry-wide practice, according to two former Twitter employees and others familiar with industry standards.

As the pushback mounts, Zatko tells TIME he stands by his allegations and for legal reasons is unable to talk about his time at Twitter beyond what’s in the disclosures. “I was aware of the most common tactics that would happen, that there would be attempts to character assassinate me or make things personal—anything that would distract from the data and the problem at hand,” Zatko says.

While Zatko describes his decision to go public in idealistic terms, the timing of the disclosures is notable. The trial to decide whether Musk must go through with his initial agreement to buy Twitter is set to start in Delaware on Oct. 17. Zatko inserts himself into this battle from the opening pages of his disclosure, claiming that Twitter is “lying about bots to Elon Musk.” Zatko may be drawn directly into the court case: Musk’s lawyer, Alex Spiro, tells TIME his team has subpoenaed Zatko, although Zatko’s lawyers say he has received no such subpoena.

Two legal experts say they’re skeptical Zatko’s claims will have a major impact on the lawsuit. He provides scant new information about spam bots, and what he does claim about them has little to do with the merger agreement. Ann Lipton, a law professor at Tulane University, says that Zatko’s claims that Twitter lied in its SEC filings will be hard to prove. “When a disgruntled employee disagrees with management decisions,” Lipton says, “that’s frequently not taken as a sufficient basis for treating an SEC filing as false.”

“The question ultimately boils down to the credibility of the assertions made by the whistle-blower, and that is usually determined by the existence of hard evidence,” says Howard Fischer, a former SEC attorney. “Twitter’s real regulatory risk lies in whether or not the documentary evidence, and not the potentially self-serving statements of a former employee, shows knowing or reckless misleading of regulators or investors in public filings and statements.”

The disclosures could have other long-lasting financial and political ramifications. The company’s stock price dropped by around 9% in the wake of the disclosures’ publication. The same day, Democratic Senator Dick Durbin and Democratic Representative Frank Pallone announced they were investigating Zatko’s claims, with Pallone calling for “the need to pass comprehensive privacy legislation.”

Zatko’s allegations have demoralized Twitter employees, some current staffers say, and may exacerbate a brain drain at a company that has lost many of its leaders and significantly slowed its spending while in Musk-induced limbo. Twitter still has a significant impact on elections and political discourse around the world, and those who are still working on its security and privacy teams will “have to work three or four times harder,” says a former Twitter employee.

Knowing that his actions would cause corporate chaos and catalyze government investigations, Zatko says he made his decision with one goal in mind: to make Twitter, and thus the world, safer. Although right now the public can only take him at his word, that may not hold true for long. When he testifies before Congress in September, Zatko—who refused to discuss the meat of his complaint in his interview with TIME—will have the legal cover to expand on the allegations, potentially revealing new and damaging details about what happened within Twitter.

Zatko is not the youthful star hacker he used to be. Two days before his interview with TIME, he broke a toe while sparring with a jiu-jitsu opponent, an accident he chalks up in part to partial paralysis of his back, which he says his doctor told him has been brought on by the stress of the past few months. Injury, however, may be necessary if you’re going to engage in the fight. “If you’re just reacting to what an adversary is doing, they’re the ones that are moving you around and manipulating you,” he says. “That’s all too common in this industry.”

—With reporting by Leslie Dickstein, Nik Popli, Simmone Shah, and Julia Zorthian

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Billy Perrigo/Washington at billy.perrigo@time.com and Vera Bergengruen at vera.bergengruen@time.com