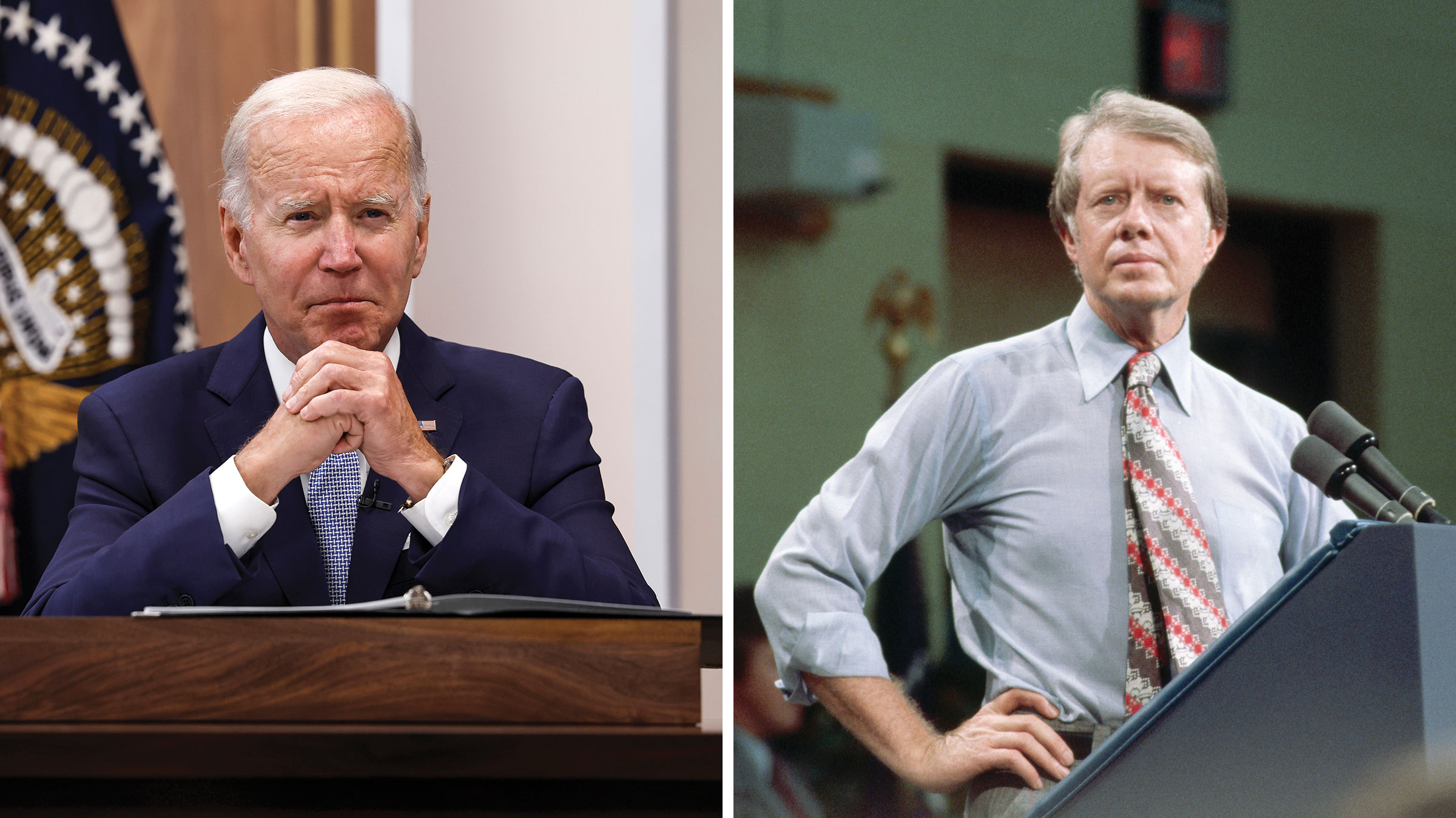

In the lead-up to the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—a law securing the biggest climate investment in U.S. history and leading to lower prescription drug costs for seniors, which President Joe Biden is set to sign this week—one particular comparison point loomed large over Biden’s economic agenda: President Jimmy Carter.

For months, conservative-leaning politicians and news outlets have derisively compared him to his predecessor. Senator Tom Cotton, an Arkansas Republican, quipped on Twitter on July 28 that “Jimmy Carter has a defamation case against anyone comparing him to Joe Biden.” In a recent FOX News op-ed, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich wrote that voters “need to reject the policy failures of Presidents Jimmy Carter and Joe Biden.” Nor were the connections coming only from across the aisle: In January, Vice President Kamala Harris drew comparisons to Carter when she spoke of “a level of malaise” in a PBS News Hour interview, echoing the former President’s so-called “malaise” speech from July 1979.

For Republicans, the references are shorthand for a failed presidency, but many historians have argued that in fact, the Carter comparisons aren’t necessarily the insult they’re intended to be. For years, the Carter Administration has been dogged by a reputation for ineffectiveness, but a recent wave of reconsideration posits that this notoriety is far from deserved, and that Carter was more successful than he got credit for at the time—and, to some political observers, the passage of the IRA shows that Biden can’t be seen as ineffective either.

Read more: Joe Biden on Vaccines, Pardons and Uniting America: The 2020 TIME Person of the Year Interview

And the fact that parallels have been drawn between the two presidencies is perhaps unsurprising. Both administrations faced a level of distrust from Americans. In a July 23, 1979, cover story headlined “At the Crossroads,” TIME described Carter as “surprisingly candid about his perception of the national mood,” which he summed up as “a ‘malaise’ of confusion, pessimism and distrust that had roots much deeper than gasoline lines or double-digit inflation.” In 2022, surveys likewise found that the majority of Americans are “dissatisfied” with the national situation.

Those two factors mentioned by Carter are making a dent now, too. Inflation preoccupied the U.S. during the 1970s and then reached a 40-year high this spring. “People are drawing comparisons because, in many ways, the trigger for inflation is much the same—having to do with oil and energy,” says Meg Jacobs, author of Panic at the Pump, about the 1970s energy crisis. During the Carter Administration as well as today, geopolitical struggle and unrest triggered oil shortages and oil shocks.

As Stuart Eizenstat, Carter’s Chief White House Domestic Policy Advisor, joked about what it was like to go to work back then, “I had to wait 30 minutes in line [for gas] to get to the White House to deal with the problem of the gas lines.” Amid discussions about whether the U.S. is currently facing stagflation (high inflation and slow economic growth), Eizenstat describes dealing with stagflation in the Carter years as “like having salt poured in a wound every single day…We tried to get OPEC to increase production and make up for the shortfall, not unlike President [Biden’s] trip to Saudi Arabia.”

However, the COVID-19 pandemic differentiates today’s inflation from the inflation Carter faced, which can be traced to 1960s macroeconomic factors “roiling” the U.S. economy, says Gregory Brew, a historian of oil and a postdoctoral fellow at the Jackson School of Global Affairs at Yale University.

“The inflation that Biden is dealing with is very different than the inflation and economic problems that Carter is dealing with,” says Brew. “Carter came into office with inflation already on the agenda. It had been a persistent problem throughout the 1970s. Our current inflation problem caught pretty much everybody by surprise when it started to appear in late 2021…Biden’s burst of inflation, by comparison, stems from the post-COVID recovery and shocks to the energy and food markets since the Russian attack on Ukraine.”

Both Brew and Jacobs point out that climate change is factoring into these policy decisions today in a way that it wasn’t during the Carter administration.

“Climate change wasn’t on the agenda the way that it is today, so that’s another huge issue that really has no parallel in the Carter era,” says Brew.

But while climate change is seen as a more urgent issue today compared to 40 years ago, Carter pushed forward the conversation about alternative energies. Under Carter, the Department of Energy was created, a bill passed that increased investments in energy technologies, and controls on domestic oil prices were dropped.

“So the question is, is this going to be the moment, unlike the 1970s, where we really see a pivot towards more sustainable clean energy?” says Jacobs. She sees the IRA as “completing what Carter started,” citing Carter installing solar panels on the White House roof and vowing that the U.S. would get 20% of its energy from solar and other alternative energy sources by the year 2000.

Read more: Former President Jimmy Carter: How Empowering Women and Girls Can Help Solve the Climate Crisis

Kai Bird, author of The Outlier: The Unfinished Presidency of Jimmy Carter, argues that another similarity between the two presidents is a difficulty getting their messages across: “Both men are not very good at communicating in front of the TV camera—Biden, partly because of his age, but also because of his verbosity and his tendency to think off the cuff. And Carter just was never good in front of the television camera, so there’s another similarity there.”

But the main Biden-Carter comparisons that Bird has noticed are rooted in what he says is an incorrect argument that Carter didn’t accomplish much. In actuality, Bird says, Carter played a key role in deregulating the airline, trucking, and alcohol industries, as well as negotiating the SALT II arms-control agreements, the Panama Canal Treaty, and the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt.

“When people say, ‘Oh, Biden is like the ineffective, hapless Jimmy Carter,’ they got it all wrong,” Bird says. “He was quite effective, and the perception of him as being weak is way off the mark. He was actually a very determined, stubborn, principled politician who is extremely hard working… I would argue Carter is not only the most decent politician to have occupied the White House in the 20th century, [but] without a doubt, the smartest, most intelligent, best-read president we’ve had.”

Biden, too, gets high marks from Carter supporters. “The Biden Administration seems to be moving along very well,” Gerald Rafshoon, Carter’s White House communications director, says. “He has good people” working for him. Bird points out that Carter enjoyed large Democratic majorities in the House and Senate, and thinks Biden has been “pretty effective,” despite razor-thin majorities in both chambers of Congress. That said, Carter had an easier time than Biden getting judicial nominees confirmed in the Senate and by this point in his presidency had “remade the federal bench,” boasting the confirmations of several African American, female, and Hispanic federal district court nominees.

But whether the comparison holds into the next election cycle may ultimately determine whether Biden is able to remain “pretty effective.”

“Everyone’s making the comparison [between Carter and Biden], both because of the levels of inflation, which we haven’t seen since the Carter period, and because of the political ramifications of that inflation,” Jacobs says. “And it’s not unreasonable to think that the situation will play out as it did for Jimmy Carter, meaning that there will be political fallout from high levels of inflation for Biden, as there were for Jimmy Carter.”

As Eizenstat recalls, ahead of the 1978 midterm elections, “Carter’s polls were plunging in part because he couldn’t get his energy package through after 18 months of negotiations with an even more heavily Democratic Congress.” Carter eventually triumphed, helping to negotiate an agreement that got Congress past a “bitter dispute” about how natural gas should be regulated. But, while the Democrats did retain control of Congress in the 1978 midterm elections—perhaps a bright sign for today’s Democrats in the wake of the IRA’s passage—Carter lost the 1980 presidential election to Ronald Reagan. In 1979 and 1980, Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker oversaw interest rate hikes as high as 20%, and the U.S. fell into a deep recession.

But Rafshoon says that it was foreign policy, not domestic issues, that led to that loss. “The main reason we lost was because we were faced with the [Iran] hostage crisis,” Rafshoon argues. The political ramifications of the IRA and modern inflation, he says, can’t be judged until closer to Election Day in 2024.

But the Carter White House may still hold a lesson for the Biden White House, Eizenstat says: “Keep moving forward. Keep your head up. Don’t show any strain. Keep your optimism.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com