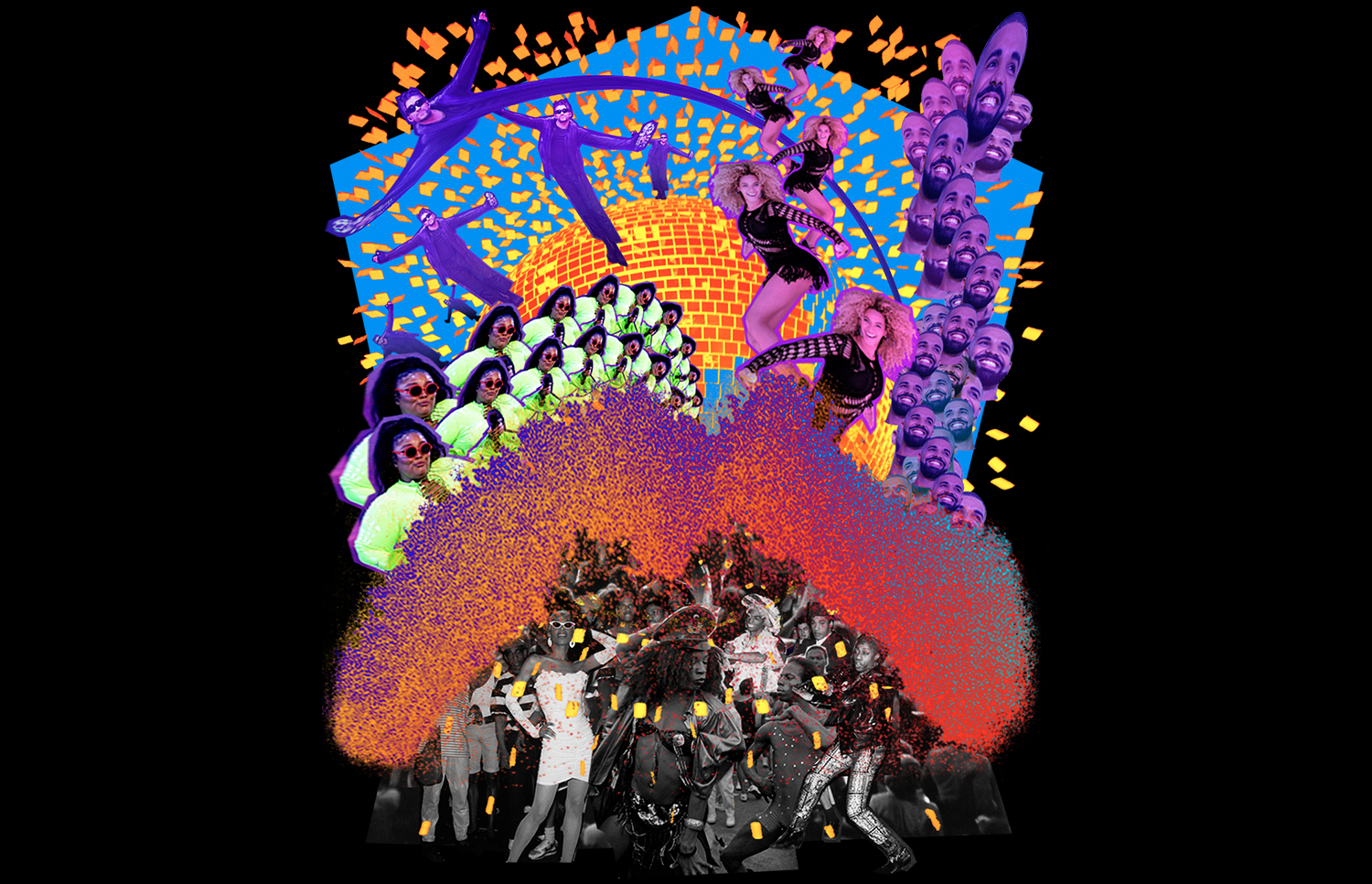

In mid-June, hip-hop mogul Drake had a surprise: his seventh studio album, Honestly, Nevermind, would drop the next day. Those who hit “play” were in for another revelation: Drake, normally a bellwether for incoming pop-music trends thanks to his ravenous appetite for the next big thing, was singing about his heartbreaks and haters over the syncopated rhythms and heavy beats

of house music.

Fast-forward a weekend and Beyoncé, a similar signpost for what’s coming in pop, released the

first single from Renaissance, her seventh album. “Break My Soul” is fueled by insistent synths

and the feeling that the world is closing in, with Beyoncé “lookin’ for a new foundation/ And I’m

on that new vibration.”

Read more: Everything We Know About Beyoncé’s New Album, Renaissance

Two of pop’s most important artists shifting in similar musical directions might be one shy of an officially observable trend, but it is noteworthy. House music has been a force in pop since its ascent from underground clubs in the ’80s, but the genre has, in recent years, waned slightly in influence. Even at its most upbeat, the storming beats and fragmented instrumentation of house recall low-lit, sweaty clubs where people are in close proximity to one another—the perfect place in a near apocalypse to, as Beyoncé wails on “Break My Soul,” go “looking for something that lives inside me.”

House music was initially a reaction to the ornate instrumentation and pop appeal of disco; in its earliest forms, it was machine-like at its core, with lengthy tracks underpinned by the steady rhythms known as “four on the floor” that would have never survived a radio edit. DJs like the Chicago club master Frankie Knuckles made house remixes of songs on the fly, mixing and editing selections from his own varied record collection over the beats.

As house music grew more popular, it moved from Black, queer spaces to whiter, straighter ones, and in the ’80s and ’90s, it enjoyed some major moments on the pop charts. Robin S’s “Show Me Love,” which is sampled on “Break My Soul,” peaked at No. 5 on the Hot 100 in 1993; other ’90s tracks like Black Box’s groove-forward “Everybody Everybody” and Crystal Waters’ thumping “100% Pure Love” jumped from dance floors to the top 40. Pop superstars dabbled in house too: Whitney Houston’s triumphant cover of Chaka Khan’s “I’m Every Woman,” as well as Madonna’s slinky “Deeper and Deeper” and Janet Jackson’s bouncy “Together Again,” showed that they were keenly aware of the sounds coming from the club.

Read more: The Best Songs of 2022 So Far

Dance music has always been an essential part of pop since the days of the Twist and the Stroll. House itself has spawned a slew of substyles since its breakthrough, including variants rooted in specific places. A few years ago, tropical house—a descendant marked by sun-dappled synths and more lightweight beats—burst out of the EDM festivals of the mid-2010s, with artists like the Norwegian DJ Kygo achieving hits through team-ups with pop artists like Selena Gomez.

It might be too soon to declare that all of pop will be taken over by house’s harder-hitting beats. But these songs, as well as recent efforts by pop futurist Charli XCX and superstar DJ David Guetta, show that the pop-music landscape of 2022 definitely feels more ready to move than in previous years—chalk it up to pandemic-era fatigue. Beyoncé’s comeback song isn’t necessarily a harbinger for how Renaissance will sound—six years ago the bare-bones bounce-trap cut “Formation” didn’t necessarily reflect the wide sonic palette of Lemonade. But the lyrics of “Break My Soul,” which include the complaint “damn, they work me so damn hard,” continue a trend of pairing club-ready beats with lyrics that speak to wider existential despairs.

Take Bad Bunny’s latest album, Un Verano Sin Ti, which fuses sounds from all over the world, particularly his home region of the Caribbean, while questioning power structures and their abuses. Or “About Damn Time,” the lead single from Lizzo’s new album Special; it’s a fizzy, skating-rink-ready rebuke to the blues, with the singer-rapper-flutist trying to beat her depression with pump-herself-up mantras (“I’m way too fine to be this stressed”). Some of the catchiest pop songs have hidden messages of despair and longing in their candy-coated structures, from the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” to Outkast’s “Hey Ya!,” but the contrast does seem more heightened with the current crop of club-ready hits.

It could be due to the way in which pop stars can be, well, stars these days. Shifts in the ways music is promoted and disseminated mean they don’t need the support of radio stations in order to be massive. As a result, they can speak, and sing, more freely—and thanks to the charts’ taking streaming numbers into greater consideration, listeners’ responses are noticed more directly. Bad Bunny’s availability on streaming services has made his appeal, fueled by his overwhelming charm, and his honesty about his personal and political stances, plain to chart watchers: Un Verano Sin Ti and its predecessor, 2020’s El Ultimo Tour Del Mundo, have both hit No. 1 on the Billboard 200. He’s also headlining stadiums this summer.

Beyoncé’s recent career makes this point in a slightly different way. Despite being considered one of the world’s biggest pop stars for pretty much all of the 21st century, she’s had only two Hot 100–topping songs since her dominant ’00s run—2017’s “Perfect Duet,” with Ed Sheeran, and 2020’s “Savage Remix,” with Megan Thee Stallion. (As of this writing, “Break My Soul” has peaked at No. 7.) Yet she can still make the earth move with an imminent album; Lemonade was bought and streamed by enough consumers to make it the fourth biggest album of 2016.

With the pop landscape continuing to be unpredictable thanks to the hitmaking ability of TikTok and the power of a good TV sync—who had Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill” in their 2022 song-of-the-summer pool?—Drake and Beyoncé’s return to the clubs provides an unexpected tonic for listeners looking to dance out their dread. Separately yet somehow together, the two used their considerable pop power to shine a light on one of modern pop’s foundational genres, luring audiences to its powerful, body-shaking rhythms.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com