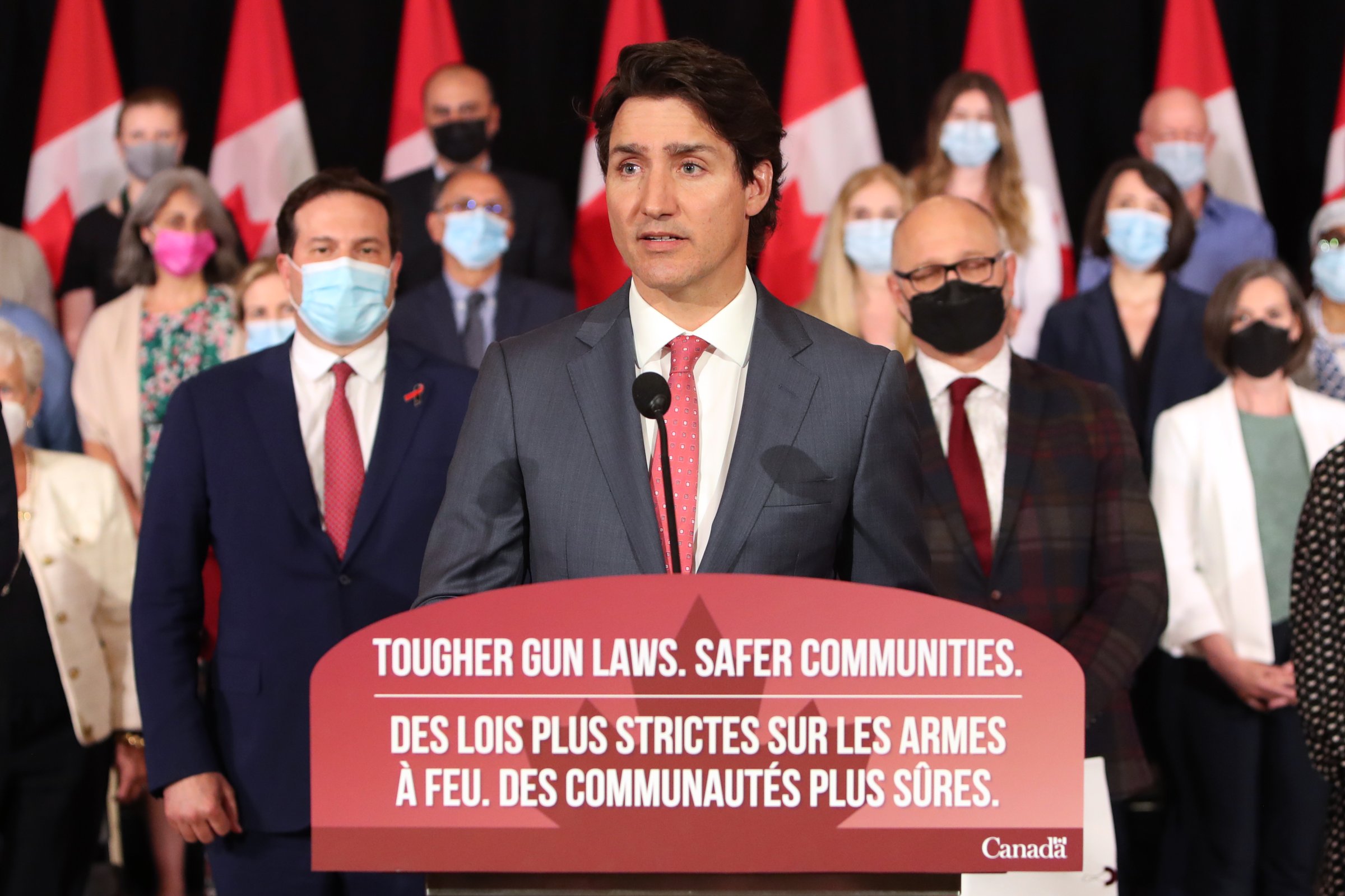

Following two horrific mass shootings, the government announced new legislation that would dramatically restrict the sale of handguns, and start a program to buy back semi-automatic assault rifles. But the proposed gun restrictions came from Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau—and the shootings happened across the border in Buffalo, N.Y., and Uvalde, Texas.

“We need only look south of the border to know that if we do not take action, firmly and rapidly, it gets worse and worse and more difficult to counter,” Trudeau said Monday in announcing the new gun control legislation.

While Trudeau cited the U.S. shootings, experts say the measures are aimed at addressing rising gun violence in the country—and fulfilling election promises to get tougher on guns. The rate of violent gun crime in Canada rose 20% in 2015 to 2020, compared with the previous six years. “Gun violence is a complex problem but at the end of the day the math is really quite simple; the fewer the guns in our communities, the safer everyone will be,” Trudeau said.

While Trudeau has made gun control as a political priority for many years, Canadians are also watching the gun violence in the U.S. closely. “Canadians pay a great deal of attention to what occurs in the United States,” says Mugambi Jouet, an assistant professor at the McGill University Faculty of Law in Montreal.

What’s in the Canadian gun restrictions?

The proposed law would prevent the importation, purchase, sale and transfer of handguns. It would also strip firearms licenses from those convicted of domestic violence or stalking. It would increase criminal penalties for gun smuggling and trafficking. And it would create a new red flag law that would allow courts to require those considered a danger to themselves or others to surrender their firearms to law enforcement.

Perhaps the most direct nod to the violence in the U.S., the Canadian government is also introducing a voluntary program to buy back semi-automatic rifles—including assault weapons like those used in Uvalde, Buffalo, and many other mass shootings. It follows a failed attempt to enact a similar program before last year’s federal election.

That measure was relatively unpopular even among gun control advocates, who felt it was not tough enough because it left it up to gun owners as to whether to give up their firearms. “The people who participate in these kinds of campaigns are typically not the people who are rerouting or trafficking guns into the illicit market. So they’re already kind of low risk people to begin with,” says Jooyoung Lee, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Toronto. “Voluntary buybacks in general don’t have a good track record. They’re not really ever shown to reduce gun violence.” New Zealand implemented a mandatory buyback program in 2019 after a gunman targeted two mosques and killed 51 people.

For some gun violence experts, it still doesn’t go far enough. Lee says the handgun freeze is a “terrible proposal”—more symbolic rather than attacking the root of the problem. That’s because most guns used in homicides in Canada are arriving from the U.S.—often smuggled from states closer to the border to be sold illegally, he says. So while the freeze targets legal imports, the measure might fall short in addressing trafficked guns, he adds.

“It’s not looking at prevention. It’s not looking at addressing the underlying conditions that are driving at-risk youth to get a gun,” says Lee. Neither are they investing significantly in grassroots programs such as violence interrupters, he adds.

Conservatives dismissed the proposals as “virtue signaling.” “It’s extremely problematic because it absolutely appears to be going after those that own firearms, but do so legally and are following all of the rules and regulations that are in place,” said Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe.

Still, the proposals will face less opposition than gun control measure in the U.S. Jouet notes that in general, it’s much easier to pass legislative reforms in Canada than the U.S. Canada’s opposition Conservative Party is also “more amenable to and less adamantly hostile” to gun control than the Republican party in the U.S. “It’s far more difficult to envision reforms in the U.S. because many people conceive of the right to their arms as key to their identity and the identity of the U.S.,” he says.

Canada’s gun violence problem

In 2020, Canada’s homicide rate rose to its highest level in 15 years—with police reporting 743 homicides across the country of 38 million people. The homicide rate of 1.95 deaths per 100,000 people is markedly lower than the U.S. homicide rate, which was 7.8 deaths per 100,000 in 2020.

But that rate is also higher than most of Western Europe and Australia, according to World Bank data on homicides. “It’s not as violent as the U.S. But when compared to other rich, wealthy nations, Canada is not faring so well,” Lee points out.

Gun control groups have blamed a relative weakening of national gun control legislation under Trudeau’s Conservative predecessor. “As we progressively strengthened gun control in Canada… we saw the rates of gun violence, particularly suicide, violence against women and so on, fall. And for the last few years, we’ve seen an uptick,” Wendy Cukier, head of the Toronto-based Coalition for Gun Control, told NPR in 2020.

What’s the gun control situation in Canada?

Perhaps the biggest difference with regards to gun ownership between the U.S. and Canada is that the U.S. enshrined gun ownership as a right in the Constitution. Canada did not.

Canada therefore has more checks and balances on gun ownership. “Canadians treat gun ownership kind of like getting a driver’s license,” Young says, explaining that gun owners are required to pass a test, take a safety course and renew their license every five years.

Conservative politics in Canada is also much more moderate compared to the U.S., Jouet says. The intensity of the movement for the right to bear arms in the U.S. is “tied to other trends that are also atypical by Western standards” such as opposition to abortion and universal health care, he adds.

Over the last decade, an increasing number of Canadians—about 1.1 million in total—are now gun owners. The number of registered handguns increased by 71% between 2010 and 2020. Canada has an estimated 34.7 guns per 100 residents, according to a 2018 study by the nonpartisan Small Arms Survey. That’s far less than the U.S., which has 120.5 firearms for every 100 residents—but still higher than many developed countries.

Lee notes that while Canada may have more effective gun laws than the U.S., the same issues around gun violence occur there, too—albeit at a lower frequency. In 2017, a gunman with a semi-automatic rifle and pistol, killed six people at a Quebec City mosque.

In 2020, after a mass shooting in Nova Scotia led to the deaths of 22 people, the government approved a ban on more than 1,500 models and variants of assault-style weapons. In addition to mass shootings, the people in Canada most heavily impacted by gun violence tend to be members of the Black and Indigenous communities. “It mirrors the U.S. in a lot of ways,” Lee says.

While recent mass shootings in the U.S., may have made this moment politically opportune for Trudeau to push new gun control measures, Canada’s rising gun violence has cemented the issue as a domestic priority.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com