Joe Biden makes his first trip to Asia as U.S. President against a tumultuous backdrop. Among other issues, his administration has been dealing with China’s refusal to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and tensions with Beijing over Taiwan. Then there’s the ramping up of missile tests by North Korea even as it locks down major cities in response to its first COVID-19 outbreak—or at least the first one that Pyongyang has admitted to.

Biden’s top foreign policy priority is containing China, U.S. diplomatic sources tell TIME, and he doesn’t want American help for Ukraine to give the impression that his focus has drifted westwards. The tour is intended to demonstrate U.S. engagement in Asia while sending a message to China and North Korea that regional alliances with South Korea and Japan remain rock solid.

Read More: The Lessons For Asia as Biden Deserts Afghanistan

Biden’s predecessor Donald Trump made a visit to Beijing the centerpiece of on his first Asian trip, but the current president is making a point of concentrating on allies.

“Biden is hoping to reassure allies about U.S. commitment that Trump sabotaged with his erratic diplomacy,” says Jeffery Kingston, director of Asian Studies at Tokyo’s Temple University Japan.

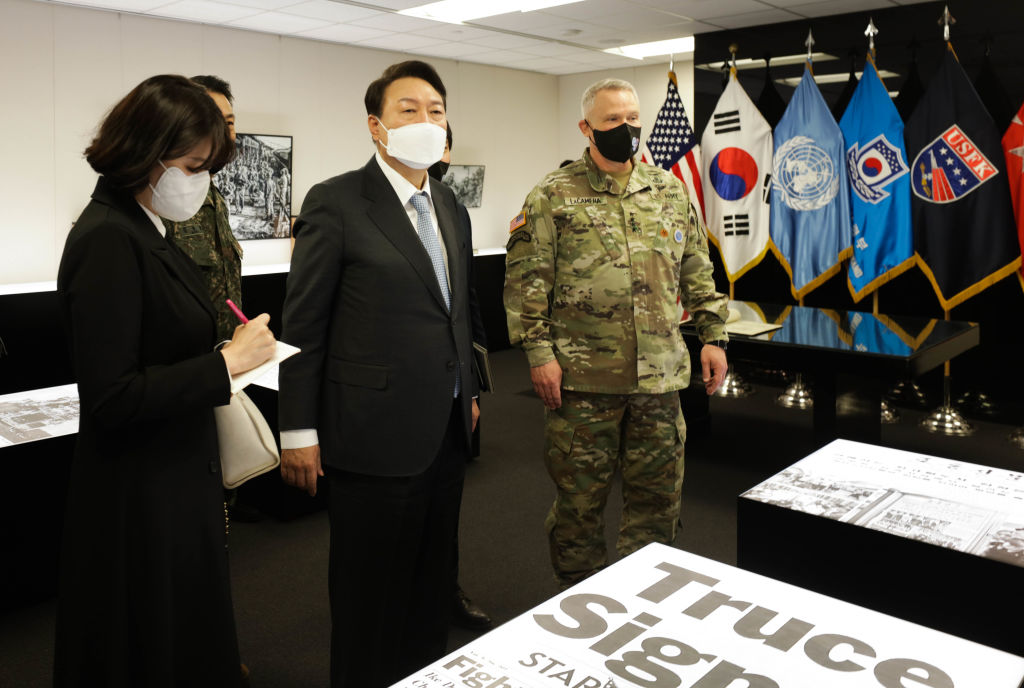

Security on the Korean peninsula will dominate Biden’s summit with new South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol in Seoul on May 21, though Ukraine and supply chain issues are also on the agenda. The following day, Biden joins a meeting of the Quad security pact in Tokyo alongside the leaders of Japan, India and Australia.

Biden’s visit to South Korea

During his election campaign, Yoon called for more U.S. THAAD missile systems to be deployed to South Korea and even raised the possibility of pre-emptive military strikes on Pyongyang’s weapons sites. While in Seoul, Biden is likely to urge Yoon to maintain this tough stance, given that Kim Jong Un has held 16 weapons tests so far this year, including a potentially game-changing submarine missile launch. There is also growing suspicion that another nuclear test looms.

But despite Kim’s bluster, North Korea is in trouble. The reclusive nation is suffering an “explosive” COVID-19 outbreak, with at least 1.2 million believed infected and more than 50 dead, according to official figures. The regime has so far refused offers of vaccines and lacks basic medical supplies. In response, major cities, including the capital Pyongyang, have been shuttered. In rural areas, work units are being kept apart. State media has advocated homespun remedies, including salt water gargles and the consumption of yogurt.

Read More: What to Know About North Korea’s ‘Explosive’ COVID-19 Outbreak

Some have suggested that the crisis may offer a window for medical diplomacy. In his first budget speech to South Korea’s National Assembly on Monday, Yoon said: “If the North Korean authorities accept, we will not spare any necessary support, such as medicine, including COVID-19 vaccines, medical equipment and health care personnel.”

However, Pyongyang’s track record from the mid-1990s, when it aggressively pursued a nuclear program despite widespread famine that reportedly killed millions, doesn’t offer much hope of a slowdown in militarization.

“The government does not care about its own people,” says Sean King, a former U.S. diplomat and now senior vice-president of political risk firm Park Strategies.

U.S. allies in Asia

It is meanwhile unclear whether Biden can push Seoul to cooperate more forcefully on countering China. Favorable views of the U.S. jumped sharply in South Korea in 2021, following Trump’s departure from the White House, and Yoon portrayed himself as staunchly pro-American during April’s election campaign.

However, he scraped through on the narrowest of margins and, given his weak mandate, may be reluctant to alienate top trading partner China, especially when improving the economy remains a key issue. “It’s not clear that Yoon will be as hard-line as the U.S. wants,” says Kingston.

Biden may try to increase pressure on China by getting Seoul to patch up differences with Tokyo and close ranks against Beijing. Relations between the two U.S. allies have been poor in recent years, owing to territorial disputes and unresolved abuses dating from Japan’s wartime occupation of the Korean peninsula. Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has made it clear that the ball is in Seoul’s court, and Yoon says he wants to improve ties but, given opposition control of South Korea’s National Assembly, making any concessions to Tokyo will be an uphill task for the South Korean leader.

Read More: Why the Quad Alliance is Contradictory and Ambiguous

Biden will also be looking for a show of unity at the Quad meeting. However, India’s refusal to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine spotlights the contradictory nature of this odd alliance. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi won’t want to be pushed too hard to take sides against Moscow, which Delhi regards as a long-time ally and defense partner. Nor will Biden be insistent, for fear of losing India’s support in America’s rivalry with China.

“It makes things a little awkward and kind of calls into question the utility of the Quad,” says King. “Here you have this grouping where you pursue shared values … [of] democracy and human rights. And then on the defining issue of the day, its most populous member doesn’t want to take a stand.”

The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework

Every U.S. president comes to Asia with something to sell and bulging out of Biden’s briefcase is his Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). First unveiled in October 2021, the IPEF is an initiative that seeks fair trade, improved supply chains, greater sustainability, and measures to reduce corruption.

Doubtless Washington will hope that the framework can mitigate the influence China wields through its Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership—a pact of 16 countries that together make up about a third of the world’s GDP. There are also hopes that the IPEF can make up for the lost opportunities of the Obama-era Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which Trump scrapped on his first day in office.

“The IPEF holds promise, but it will need to be well engineered and managed if it is to advance U.S. economic and strategic interests, become a credible alternative to other regional initiatives, and be seen by allies and partners as a durable U.S. commitment to the region,” wrote Matthew P. Goodman and William Alan Reinsch in a report for the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Read More: The U.S. Could Be the Big Loser in the Huge RCEP Deal

It will be asked why the U.S. doesn’t simply join the Japanese-led Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership—which evolved from the TPP after America’s withdrawal—instead of pitching an entirely new agreement that might be seen as adversarial to Beijing. Many Asian nations balk at being continually asked to chose between the U.S. and China.

“I guess it’s good that we’re pushing something, but I’d rather just see us get back in TPP,” says King.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com