The ascent of Philippine dictator’s son Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. to power marks an important turning point for the Southeast Asian country as it tries to find a balance in its relationship with the U.S. and China.

Outgoing President Rodrigo Duterte’s foreign policy approach was, for the most part, marked by hostility toward the West in general and the U.S. in particular. Ever since a 2002 bombing in Davao City—his home turf—where U.S. operatives allegedly spirited away an American suspect without the approval of the Philippine authorities, Duterte has been vocal against what he sees as Western meddling in the country’s affairs. He also recognized China’s growing might and cultivated Beijing as a hedge against Washington. Case in point: he never pressed a 2016 U.N.-backed ruling invalidating China’s sweeping claims over the South China Sea, where Beijing has built several artificial islands and militarized some of them. Instead, Duterte trod lightly on Chinese maneuvers and construction activity in the strategic waterway.

Local and international observers say Marcos Jr. will broadly follow Duterte’s approach to Beijing as part of his promise of policy continuity, but with a slightly different tack. He doesn’t have the “ideological orientation and the personal resentment that Duterte has toward the West as a whole,” says Richard Heydarian, a political science professor at the Polytechnic University of the Philippines.

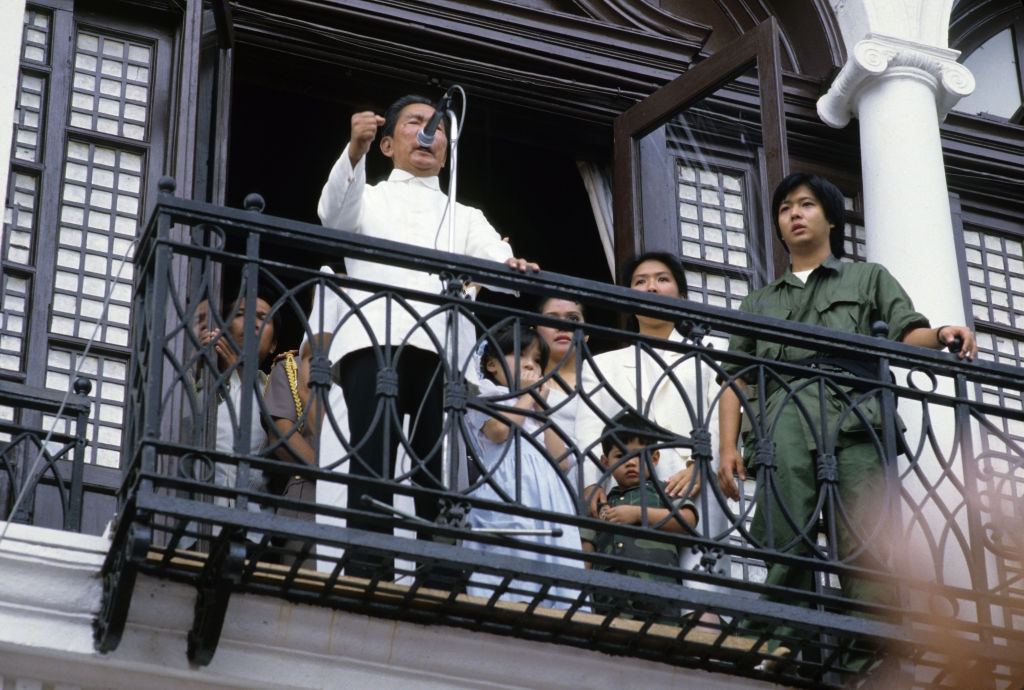

Marcos Jr. has his own issues with the West, however. He, his mother, and his father’s estate continue to evade a U.S. contempt ruling in 1995 in connection with a human rights class action suit against his father. Being the son of Ferdinand E. Marcos, whose 21-year rule in the Philippines gained notoriety for its state-sponsored killings, corruption and kleptocracy, isn’t helping.

But these factors will not strain ties with Washington, says Joshua Kurlantzick, senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. He points out that Duterte never visited the U.S. as president and was openly hostile to it, yet Washington continued to maintain its defense alliance with Manila.

“It is true [Marcos Jr.] faces a potential arrest for contempt of court if he comes to the U.S.,” Kurlantzick tells TIME. “But the White House might find a way to massage that, or he could come to the U.S. for the United Nations General Assembly, which is generally a safe zone for people who might otherwise face charges in the U.S., and meet with U.S. officials.”

The U.S. and the Philippines established formal diplomatic relations in 1946, after American soldiers joined Filipino forces to defeat Japanese invaders during World War II. A 1951 pact requires both countries to support each other if attacked by an external force. The growing rivalry between America and China, and the Philippines’ geographic location, make the Southeast Asian nation an invaluable ally for Washington.

Pushback may come if democracy in the Philippines takes a further hit under Marcos Jr., Kurlantzick adds. But Heydarian thinks Washington has “no choice” but to engage with Manila, to keep it away from Beijing and Moscow, both of which have been spreading their influence in the region.

Balancing China and the U.S.

China is the Philippines’ top trading partner. Its direct investments in the Philippines reached $17.46 million in the first half of 2021. Duterte had called for more Chinese involvement in big-ticket infrastructure projects but many of them were delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Some Philippine economists and lawmakers now warn that further Chinese dealings would put the country at risk of more burdensome loans.

Kurlantzick says any hard pivot to Beijing will also be difficult for Marcos domestically. The incoming Philippine president will be limited by negative public opinion against China, a traditionally pro-U.S. security establishment, and Duterte’s own recent warming up to Washington.

Lucio Pitlo III, a research fellow at the Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation, says Beijing has been wary of joint U.S.-Philippine military drills and hesitant to push forward with big investments in the Philippines amid security concerns. Marcos Jr. will have to tread carefully between the two powers to leverage relations with each of them without antagonizing the other. Both U.S. President Joe Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping congratulated Marcos Jr. on his victory, reinforcing the importance of maintaining cooperation on the two fronts.

“The U.S. and China will remain important partners for the Philippines—economically, and security-wise,” Pitlo tells TIME. “Of course, as any country in Southeast Asia, we should avoid choosing between the two because both of these powers can do for us the things we need.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com