The problem with Airbnb, according to its CEO Brian Chesky, is the search box. When users open the platform, they are asked a question: Where do you want to go? This, Chesky has come to realize, is the wrong way to approach travel. Chesky wants Airbnb to meet users sooner on their journey, and the first step of any trip is not to figure out where you’re going, but to imagine yourself anywhere other than where you are. At the same time, Chesky also seems to realize that Airbnb’s standard way of doing business has created some unforeseen problems.

Airbnb, this week, is implementing what it calls its biggest update in 10 years. There are three main changes to the site. Users will be provided with built-in travel insurance, in case of unforeseen events. (Of the ‘this place sucks’ kind rather than the global pandemic kind.) The website will show them how they could split their journey between two destinations and Where do you want to go will not be the only option they are given for planning their getaway.

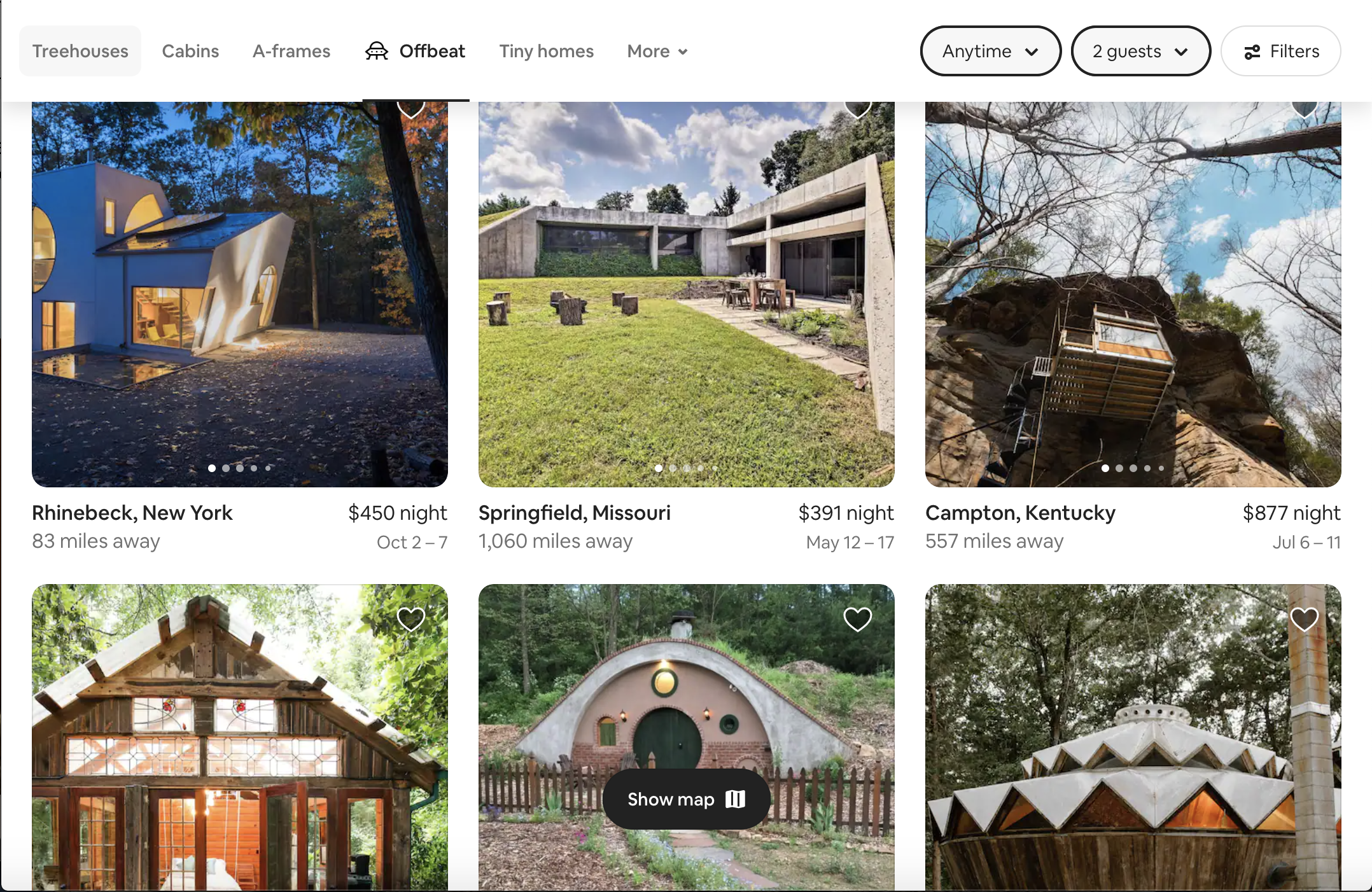

A combination of A.I. bots and humans have combed through the site’s millions of listings and now offer 56 different search options. If a user has always wanted to stay in a cave, or a yurt, or a castle, or a treehouse, she can search for those. If, he, like the Rhode Island School of Design-trained Chesky, is a fan of architects, he can search Rem Koolhaas or Frank Lloyd Wright by name. (In fact, nearly all the architects are name-checked in this category, an innovation Chesky finds particularly gratifying.) If a family wants to go to the mountains or a lake or skiing or somewhere to play a grand piano or cook in a high-end kitchen, they can search under those categories. If all they want is a really epic pool, there are several thousand options for that.

Read More: “The Office As We Know It Is Over,” says Brian Chesky

“We’re in 100,000 cities,” says Chesky, sitting in an Airbnb in the New York City’s East Village neighborhood, a few days before the update goes live. “The problem is you will only type in what you can think of, and what do people think of? Las Vegas. New York. Rome. Paris Miami. L.A. Before the pandemic, a lot of people were going to a lot of the same cities.”

Also before the pandemic, Airbnb had been working on an airline-booking app and a travel magazine to get access to travelers’ attention earlier in their vacation planning, or “top of funnel,” as Chesky puts it. The company had to abandon those plans when travel—and Airbnb’s revenues—came to a standstill a couple of months into the pandemic. He says he might not pick them up again. It seems he’s found a better way to get there.

The pandemic initially hit Airbnb hard, with a billion cancellations. The company was forced to lay off about a quarter of its employees, pause all its paid marketing, borrow money to keep the company afloat and delay its IPO. It bounced back fast, and by December 2020 managed to pull off an initial public offering. “Airbnb recovered faster than most other travel companies during the pandemic,” says Chesky. He calls the last two years “the most productive in our history.”

Nevertheless, the company has had three years of poor financial performance, posting losses of $674 million, $4.58 billion, and $352 million for 2019, 2020, and 2021, respectively. Since its IPO, the stock has fallen nearly 26%.

At a press launch of the new features a few days later, replete with a film of Chesky traveling to various exotic Airbnb listings with his dog, Sophie Supernova, who made a live appearance later in the proceedings, he compared Airbnb’s photo-heavy new site to his main competitors, saying “I just don’t think travel sites should look like online casinos.” He booked a split stay in Kentucky live for the gathered press. (With a net worth of about $9 billion he can afford the cancellation fee.) And he geeked out over the incredible dwellings that people are offering, including a literal yellow submarine, in New Zealand.

The redesign may seem like little more than a nifty upgrade to vacation-seekers; another option in a sea of choices. It was possible to find many of the qualities the new site offers on the old site with slightly more sophisticated searching skills. But Chesky, whose parents are social workers, appears to harbor hope that the changes might also address several of the social problems that Airbnb, and the short term rental market generally, have been accused of generating, including an unmanageable influx of tourists to certain areas, and skyrocketing rent increases.

“Overtourism isn’t too many people traveling in the world,” says Chesky. “Overtourism is too many people going to the same place at the same time. We’re trying to actually help solve this problem. We want to make [Airbnb’s app] not just about the destination, because if it’s about the destination, it’s only about the ones you can think to type in, and we’d like to redistribute people.” Similarly the split stays upgrade offers people a few days in one town and a few days in a nearby place, thus encouraging travelers to widen their horizons.

It’s clear Chesky is not thrilled that numerous studies point to Airbnb and other short term rental outfits as one of the drivers of unaffordable housing. When landlords can make in a few nights what they might otherwise make in a month, cities struggle to keep enough rental homes on the market. And as the short term rental market booms, some investors are buying homes in popular tourist regions, just to Airbnb them. This, among other factors, has left many cities with an affordable housing shortage, where teachers and public servants can’t afford to live in the areas where they work.

Read More: Why Phoenix—Of All Places—Has The Fastest Growing Home Prices in the US

“When you build a platform, and hundreds of millions of people use it, it’s always gonna have unintended consequences,” notes Chesky, who is quick to point out that AIrbnb also helps keep people in their homes, by providing them with income. Indeed the business started in his own home when he and his roommate couldn’t afford to make their rent. “If you give power to people, they’re going [use it] in ways you don’t intend. And then you’re going to need to make some adaptations.”

His company’s adaptations include working with civic regulators and to try to sprinkle the visitors around a bit more. “We want to partner with cities,” says Chesky, his voice speeding up a little. “If there are issues with housing, we will work with the cities to comply with registrations. We’ve done that in hundreds of cities. But we’re also going to try to help redistribute people and help them stay longer.”

One way in which Airbnb might solve some of the problems its success has inadvertently caused would be to use the platform to help house those displaced from their home by rising prices. Its hosts have already provided shelter for 20,000 Afghan and 20,000 Ukrainian refugees, and Airbnb.org, the company’s philanthropic arm, works with domestic violence organizations to provide housing for women who have had to flee their homes, so the company has a prototype to work with. But Chesky’s not sure. “Homelessness is something that absolutely, I’m interested in helping in some way,” he says. For now he’s more interested in refugees, many of whom are being housed by Airbnb hosts at no charge. “I think the refugee crisis is so great. And there’s so few people working on it. So I think that we maybe are in a unique position to help make a dent in that problem.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com