The city of Nome, on Alaska’s Bering Sea coast, has long been the home of adventurers, chancers, and the fiercely independent who would rather live off the land than do their shopping at Walmart.

Originally a native Inupiat settlement that was taken over by miners in the 1899 gold rush, it is perhaps best known as the end point of the celebrated Iditarod dogsled race, which is run every March in commemoration of an epic effort to deliver essential medical supplies during a 1925 diphtheria outbreak when bad weather prevented airplane access. To this day there are no roads connecting the settlement to the rest of the U.S., or to the rest of Alaska, for that matter. The options are dogsled, snowmobile, sea, or air.

Opting for the latter, I landed in Nome (pop. 3,699) in late September. As I waited for my suitcase, I struck up a conversation with a man who called himself Yukon John. The unusually long summer season had been a good one for the gold miner, he said. To prove it, he pressed a small, heavy-for-its-size plastic jar into my hands. It was full of granulated gold, panned from the mineral-rich sandbanks just offshore. Then he added a trio of thumb-size nuggets. That was just a tiny sample of his latest haul, he told me. Last spring the ice that usually locks the coast in an impenetrable shield broke up early, and if the previous year was anything to go by, it wouldn’t re-form until late fall. That gave Yukon John plenty of time to dredge for gold at his Bering Sea claim. The miner said he doesn’t spend much time thinking about global warming, but if climate change means more opportunities for hitting the sandbanks, well, “bring it on. The way I see it, we have to take advantage of whatever comes our way.”

Yukon John’s fortune could be Nome’s downfall. Without the protective sea-ice shield, winter storms batter houses and buildings along oceanside Front Street, blasting past the rock barriers and tearing up the pavement. Permafrost, the layer of frozen soil and ice that serves as the Arctic region’s bedrock, is starting to thaw because of rising temperatures, and the entire town is buckling in a slow-motion earthquake. Parts of the Nome airport runway have cratered, and houses slump at odd angles, their foundations propped up by cement blocks and wooden 4-by-4s stacked in Jenga formation. The loss of thick sea ice means the Indigenous groups that make up half the town’s population, and most of the surrounding communities, can no longer reliably hunt, harvest, or fish the foods that sustain them year-round. Meanwhile, unusual winter weather conditions—rain, wind, insufficient snow—have in recent years forced Iditarod dog mushers to reroute or stop early.

Overall, the Arctic is warming four times as fast as the rest of the planet. In mid-March, there was at least one day where temperatures hit as high as 30°C (86°F) above the March average near the North Pole. Within a few years, says Diana Haecker, the Nome-based editor of Mushing Magazine, the Iditarod may not be able to finish in Nome at all.

Instead, a changing climate could turn Nome, one of the U.S.’s northernmost ports, into an entirely different kind of destination. Layered with thick ice most of the year, the Arctic Ocean has historically been all but impassable, but warming temperatures have seen sea-ice volume reduced by two-thirds since measurements were first taken in 1958. A 2020 study published in Nature Climate Change predicts mostly ice-free Arctic summers as early as 2035 if greenhouse-gas emissions are not radically reduced. Ships will soon be able to sail directly across the top of the world, bringing new commercial, political, and economic opportunities for Arctic towns in their path, while substantially reducing transit times between Asia and Europe by up to a third compared with taking the Suez Canal.

Even as it bodes catastrophic change elsewhere on the planet, an ice-free Arctic offers immense opportunities for resource extraction—U.S. congressional research estimates that there is $1 trillion worth of precious metals and minerals under the ice, along with the biggest area of untapped petroleum deposits left on the planet. Perched on the edge of the Arctic, Nome could reap that windfall, becoming the polar region’s Panama City or Port Said. “Up here, climate change can be an opportunity if it’s managed right,” says Drew McCann, director of the Nome Convention and Visitors Bureau. “We either embrace it or we are going to be left behind.” To profit from the already increasing polar traffic, the city of Nome proposed a port expansion in 2013 to make room for deep-draft cruise liners, Coast Guard vessels, oil tankers, and shipping liners. Two years later, the Army Corps of Engineers backed the $618 million project and promoted Nome as the top candidate for America’s first deepwater Arctic port. The project received $250 million in January from the federal infra-structure package and will likely break ground in 2024. “The port of Nome is poised to be that epicenter of America’s marine presence in the Arctic,” said Alaska Senator Dan Sullivan. “In addition to bolstering our national security interests, this project will lead to greater economic opportunities for residents of northwest Alaska.”

Though unchecked climate change on the whole is devastating for life on earth, there will be, inevitably, some winners. Siberia could become the world’s next breadbasket, Canada the next wine giant. Nome’s efforts to capitalize on its port, even as its shores erode and its sewage system shatters under the pressures of thawing permafrost, are echoed across the polar region as communities adapt to a fundamentally and rapidly changing Arctic. On the one hand, communities in the region face cultural and environmental catastrophe; on the other, they are starting to play host to a modern-day gold rush at the top of the world—one that invites geopolitical tensions as rival nations compete for resources, be they fish, minerals, or shipping routes.

Read more: One Island Nation’s Controversial Plan To Take Climate Justice Into Its Own Hands

The Russian government is already positioning itself as a net beneficiary of global warming, writing in its 2020 Arctic Strategy that “climate change contributes to the emergence of new economic opportunities.” With half the Arctic coastline under its control, it’s not hard to see why. Led by Rosatom, a state-owned nuclear technology and infrastructure enterprise, the country has invested approximately $10 billion to develop ports and other facilities along a 3,000 nautical-mile-long shipping lane that stretches from Murmansk, near the Finnish border, to the Bering Strait. The Northern Sea Route offers the shortest passage between Europe and Asia, shaving nearly two weeks off a journey around India, while saving fuel, limiting vessel wear and tear, and reducing emissions. The investments are already paying dividends. In 2010 international cargo shippers made only one full Northern Sea Route transit. In 2021 there were 71, according to Norway’s Nord University’s Centre for High North Logistics.

Russia is building up its existing 40-strong icebreaking fleet by commissioning at least half a dozen nuclear-powered heavy icebreakers at a cost of $400 million each. When the first of the newest batch—the world’s biggest and most powerful, according to Russian officials—launched its maiden voyage in 2020, Russia hailed it as the start of a new era of Arctic dominance. In 2021, commercial tankers, equipped with special ice-hardened hulls, started transporting natural gas between Russia’s Arctic coast oil installations and Chinese ports in the middle of winter—a strategic advance that results in a timely lifeline for Moscow if European nations follow through on threats to cut off purchases of Russian gas because of the conflict in Ukraine. “The creation of a modern nuclear icebreaker fleet capable of ensuring regular year-round and safe navigation through the entire Northern Sea Route is a strategic task for our country,” said Vyacheslav Ruksha, head of Rosatom’s Northern Sea Route Directorate, in a statement.

When one of the world’s largest container ships became wedged in the Suez Canal in March 2021, Russia pounced on the resulting week-long global shipping stranglehold as a marketing opportunity. “The Suez precedent has shown how fragile any route between Europe and Asia is,” Vladimir Panov, a Rosatom representative told the Interfax news agency. The Northern Sea Route, he boasted, “makes global trade more sustainable.” Given current warming trends, Rosatom expects that the route will be fully competitive with the Suez Canal by 2035.

Other nations, especially those with land in or near the Arctic Circle, are eyeing the Russian buildup with concern. It’s one thing to dredge a canal through your own country and charge transit fees. It’s another thing entirely to establish a commercial trading route in international waters. Admiral Karl L. Schultz, commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard, worries that the Russians might try to recoup their investment in icebreakers by turning the Northern Sea Route into a kind of marine toll road, requiring—and charging for—specially licensed pilots and icebreaker escorts through the passage. “If you can knock 10, 11 days off the transit between Shanghai and Europe on a repetitive basis and in a cost-effective way, that’s worth something,” he tells TIME. “Of course they want to profit from that.” But doing so threatens one of the fundamental tenets of the high seas: the freedom to navigate.

Russia isn’t just building up ports. For the past decade, the country’s leaders have increasingly voiced their desire to make the Arctic a sphere of military and economic expansion, to counter what they perceive as U.S. and NATO challenges to Russian interests in the region. Satellite imagery released in April 2021 showed Russia expanding its military capabilities in the Arctic by building new bases and modernizing existing ones. In August, the northern fleet of the Russian navy undertook a series of military drills involving at least 10,000 personnel on a marine battalion’s worth of combat ships, submarines, support vessels, and aircraft. The Russian state media agency TASS has leaked government plans to establish a new navy division, dubbed the Arctic Fleet, which would be responsible for securing the country’s Arctic interests. “It absolutely makes me a little bit concerned about what’s going on,” says Schultz. He was speaking from the deck of the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Healy as it transited the Canadian Arctic in August. The 23-year-old Healy is the U.S.’s most technologically advanced icebreaker. The country has only one other, and it is nearly 50 years old. If the U.S. is to keep pace with Russia in the Arctic, says Schultz, it will need to increase its Arctic-capable fleet. “Presence equals influence. And we don’t have a lot of presence up here.”

Read more: Why a Warming Arctic Has the U.S. Coast Guard Worried About the Rest of the Country

Influence will matter when it comes to control of the region’s petroleum reserves, seabed minerals, and—in a newer development—seafood. Warming oceans are pushing global fish stocks northward, into polar areas where rival nations could clash over fishing rights. The Bering Sea, shared by Russia and the U.S., is already home to approximately 40% of U.S. fish and crab stocks, and rivals New England for the most profitable U.S. fishery. This could become an unexpected flash point as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine ratchets up tensions with the U.S. Jeremy Greenwood, a fellow with the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., and a U.S. Coast Guard officer, isn’t expecting a hot conflict, but he is concerned that Russia might infringe on a maritime boundary that, while negotiated, was never formally agreed to by the former Soviet Union. “The Russians have always hated it,” Greenwood says. An infringement “would lead to chaos in the Bering Sea. We’d be seizing each other’s vessels for illegal fishing. I know it sounds stupid to talk about crabs in the context of Ukraine, but countries have literally gone to shooting wars over fisheries. It brought us to the brink during the Cold War. It’s a big deal.”

The Alaskan fishing fleet got a glimpse of what that could look like in August 2020, when the Russian navy conducted military operations inside the U.S. economic zone of the Bering Sea and warned all boats in the area to get out of their way. The U.S. Navy responded, belatedly, by conducting its own operations inside the Arctic Circle in March. It called the exercises “Regaining Arctic Dominance.” The U.S. military followed up by strengthening its overall Arctic strategy, which now includes plans for multiple polar vessel ports in the region, and a possible home base in Nome.

As climate change redraws the Arctic map, regional cooperation over fish stocks, shipping routes, research programs, and resource extraction will be vital to protect what was once optimistically dubbed the Pole of Peace by the last Soviet President, Mikhail Gorbachev. The immediate challenge: seven of the eight nations that make up the Arctic Council, established in 1996 to facilitate cooperation and collaboration in Arctic affairs, put a stop to all joint activities to protest the invasion of Ukraine by the eighth member.

As climate change redraws the Arctic map, regional cooperation over fish stocks, shipping routes, research programs, and resource extraction will be vital to protect what was once optimistically dubbed the “Pole of Peace” by the last Soviet President, Mikhail Gorbachev.

Climate scientists tracking the global impacts of polar-ice melt like to say that what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. The inverse, it seems, is also true.

Diana Haecker remembers the exact day that climate change became real to her. Haecker, who in addition to owning Mushing Magazine is the editor of the Nome Nugget, Alaska’s oldest continuously published newspaper, leafed through a book of bound archives at the Nugget offices in September. She paused at a cover photo taken on Feb. 20, 2018, from the shore of Little Diomede Island, the U.S.’s westernmost outpost in the Bering Strait. You could see nothing but water and waves all the way to the horizon. “When I saw this photo, I had to catch my breath because that is so scary,” says Haecker. All of this should be a blanket of ice, she recalls thinking. “That is when I realized we were probably past the tipping point.” A headline in that week’s edition was equally frightening: “Nome at 51°F, Record High Temperatures Melt Winter Away.” The ice didn’t return that year.

Sea ice doesn’t just protect Arctic coasts from savage winter storms. It’s also an essential element of the region’s—and the world’s—food web. Algae growing underneath feeds the fish larvae and tiny crustaceans that are the food source for most ocean inhabitants, and marine mammals like seals and polar bears need the ice floes to hunt and give birth. Furthermore, Alaska’s coastal Indigenous populations rely on sea ice for subsistence hunting. One seal can keep a family in meat for a year. In communities around Nome—where groceries are flown in at great expense, a watermelon can cost $50 and a frozen Thanksgiving turkey up to $60—hunting is not a pastime, it’s a lifeline. “The ocean is our grocery store,” says Austin Ahmasuk, a marine advocate at Kawerak, a regional nonprofit that serves the Alaska Native residents of the Bering Strait region. “Subsistence foods—animals and fish, birds, resources from the land and water—collectively comprise a majority of a person’s diet in a [Native Alaskan] village.”

Read more: Climate Change is Decimating the Chinstrap Penguins of Antarctica

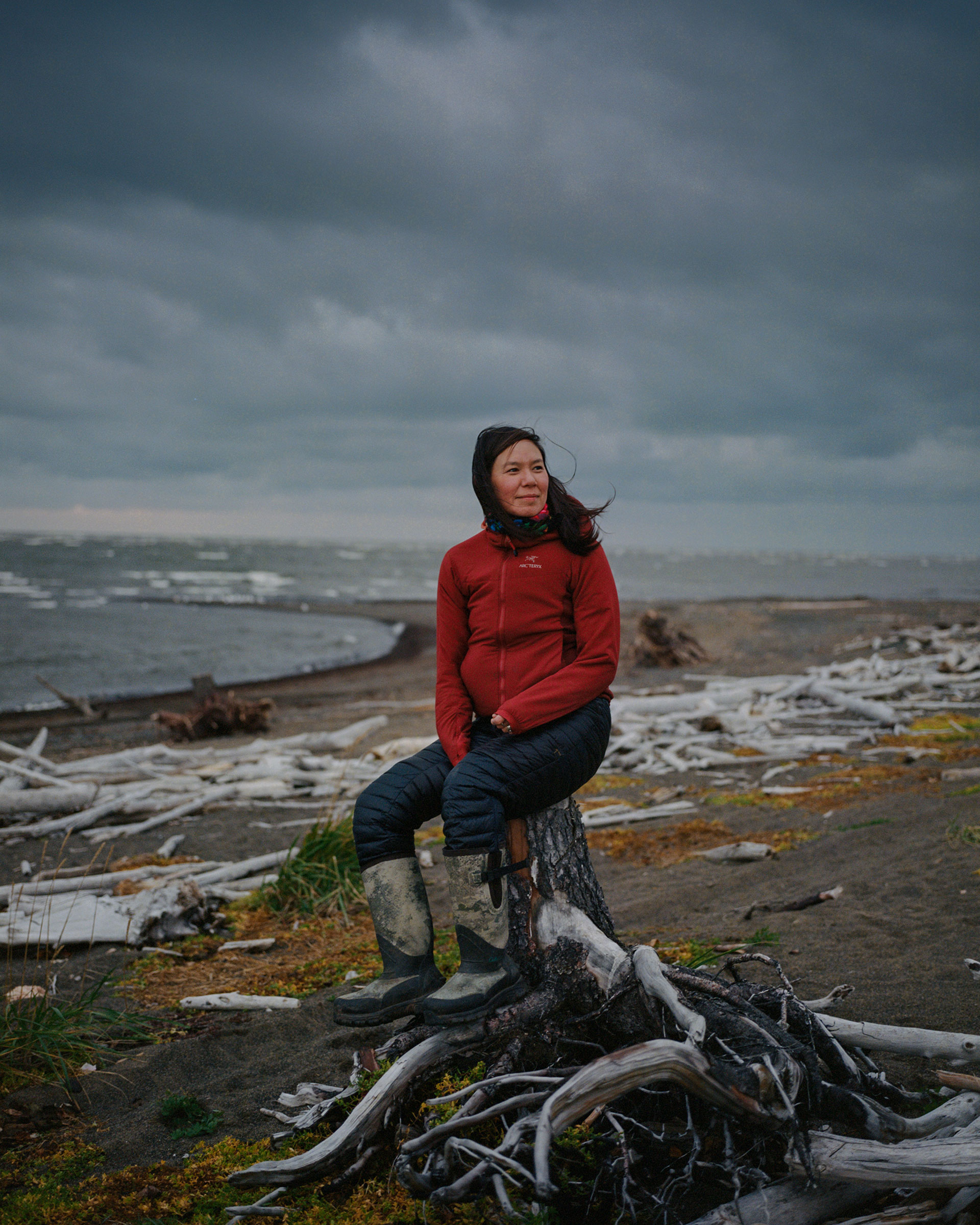

The latest report from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change noted that “increasing weather and climate extreme events have exposed … people to acute food insecurity and reduced water security, with the largest impacts observed in many locations and/or communities in … the Arctic, especially for Indigenous Peoples.” Already communities are starting to adapt. Some have started hunting moose, a once foreign species that is now moving northward into the tundra as new vegetation takes root in the thawing permafrost. On the coast, pollock is starting to replace the cold-loving salmon and arctic char that used to dominate the northern Bering Sea. “As we continue to warm, we’ve got to come up with new words,” says Melissa Maktuayaq Johnson, a former executive director of the Bering Seas Elders Group from Nome who is now working to promote Inupiaq heritage and language. “The other day, someone asked me the Yup’ik word for octopus. We don’t have one, because octopus wasn’t here before.”

Even the old canard about Eskimos having a hundred words for snow needs to be updated in a grim vocabulary for a warming world. Some Alaska natives have started using the Yup’ik neologism usteq to refer to rapid, climate-driven erosion and ground collapse caused by permafrost melt. Permafrost researchers are adopting it as well. “It kind of encapsulates everything we are seeing right now, how the cause and the effect are related,” says Sue Natali, a permafrost specialist who leads the Woodwell Center’s Arctic Program.

Adaptation is the climate world’s anodyne word for the wrenching decisions that must be made as threatened communities face the realities of irrevocable change. Dictionaries will have to be updated, communities will have to craft new traditions, and diets will change. Shishmaref, an island community not far from Nome, lost several buildings and a burial ground to usteq. In 2016 a majority of residents voted to permanently relocate to the mainland. Nome may yet be able to surf the looming disruption with minimal loss if it can get ahead of the change. When the Crystal Serenity became the first large cruise ship to traverse the Arctic in 2016, Nome was one of its first stops on the 32-day voyage, bringing in more than 1,000 day-trippers eager to spend money at its cash-strapped businesses. Now, following a COVID-19 pandemic pause, 27 cruise liners are scheduled to stop at the frontier town this summer. During my visit, boats had to anchor offshore and ferry in tourists or goods by smaller craft; when the port is lengthened and deepened, they will be able to park alongside the jetty. “This is a real opportunity for Alaska and for Nome and for those travelers coming over the Northwest Passage,” said Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy on a visit to Nome in August. “Hopefully it means more jobs for the area.”

A study undertaken by the Nome Visitor Center estimates that each cruise-line tourist brings in several hundreds of dollars to local shops and tour companies. But bigger boats also mean that the cost of bringing in goods, from construction materials to fuel, watermelons, and frozen turkeys, would go down, making life more affordable for residents. To Nome Harbormaster Lucas Stotts, the port extension can’t be built fast enough. “Thinking ahead 10 years, much less 20 or 30, there will be even more traffic and we will be even further behind the curve. We have some catching up to do.” Indeed, U.S. investment in Arctic ports and waterways already lags behind that of the other Arctic nations.

But a deepwater port in Nome could bring problems as well. More traffic means an increased risk of introducing invasive species hitching rides in the hulls of foreign vessels, which could devastate a Bering Strait ecosystem already under pressure from climate change. Maktuayaq Johnson says increased noise from the recent uptick in shipping is already disturbing the ocean ecosystem, driving fish and marine mammals away and disrupting the Native subsistence lifestyle. More ships mean more exhaust fumes that blacken what sea ice remains, accelerating the melting process. By and large, she says, Nome’s native community has not been involved enough in the planning process. “Development is important. But it can’t just be about economic gain. You’ve got to incorporate how this will impact our culture, our language, and our way of life. Right now the port expansion feels like one more opportunity for outsiders to come in and get that monetary gain.”

Read more: After Visiting Both Ends of the Earth, I Realized How Much Trouble We’re In

To Denise Michels, a Native Alaskan and, as Nome’s former mayor, an early supporter of the port expansion, the project is more about protecting the community than profiting from climate change. The more the Arctic warms, the more boats will come through the Bering Strait. Nome has to be prepared for that and prepared for the consequences as well; she envisions a search-and-rescue station that could help mariners in distress or send out emergency containment efforts in the case of an oil spill or other environmental crisis.

A port expansion, done right, should include the authority to direct traffic away from fish-spawning grounds or nurseries at certain times of the year. “We can’t stop the traffic. What we can do is try to benefit from it. That’s how we adapt to climate change.”

Alaska’s earliest residents not only survived but thrived in one of the harshest environments on earth through a process of continuous adaptation. Resisting change was not possible, not then and certainly not now, when even were global greenhouse emissions to stop tomorrow, the Arctic would continue to warm for decades more because of climatic processes already set in place. Seeking opportunities in a rapidly changing region, whether it’s better access to mineral resources, more efficient shipping routes, or new fishing grounds, is simply the newest—and some would say, the most practical—form of adaptation. As long as those opportunities don’t just make the problem worse, for the climate, for the region, and for the people who live in it.—With reporting by Eloise Barry

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com