This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

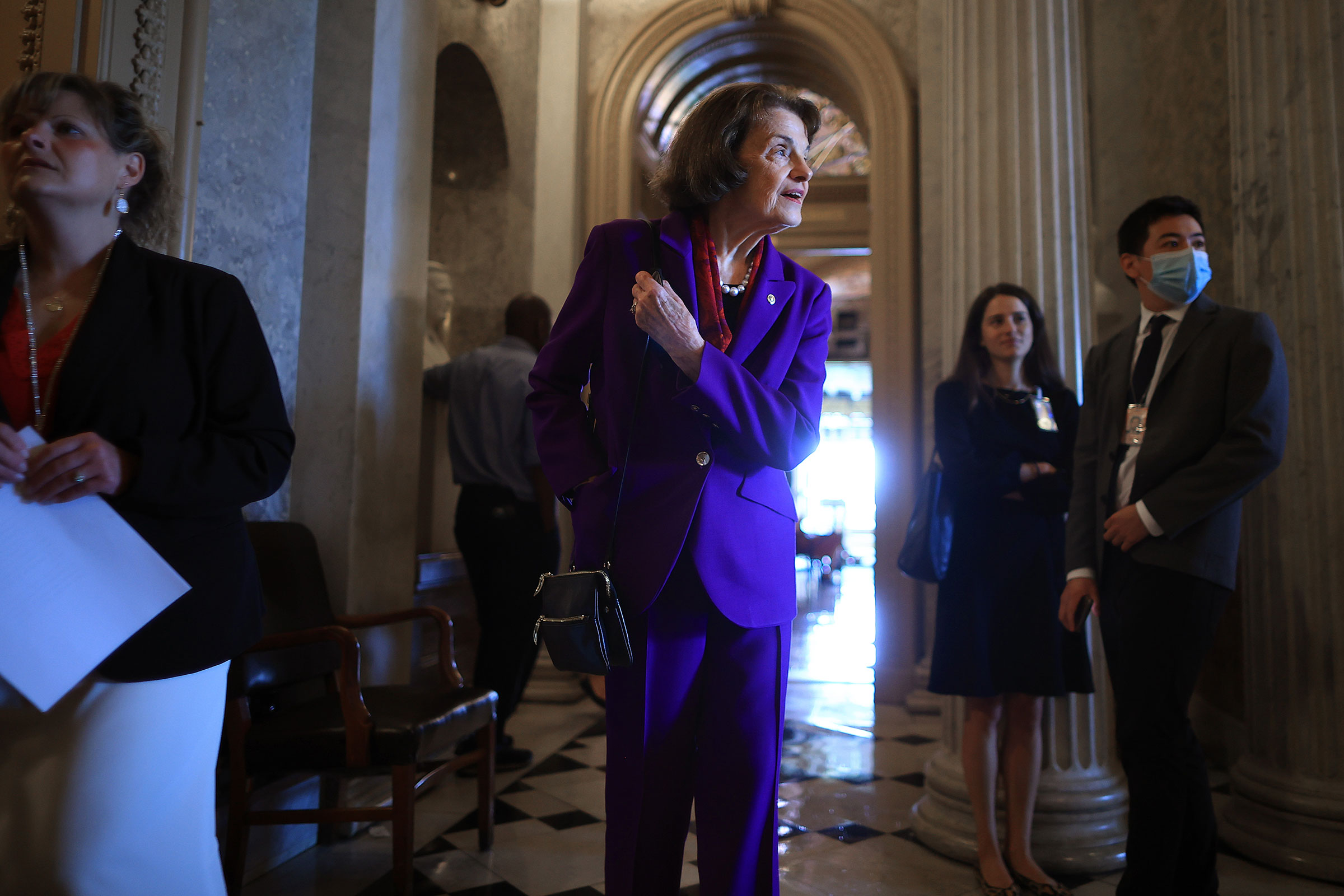

Washington is a place full of secrets that no one keeps. One is that the Senate is a gerontocracy, where age is currency and longevity is strength; when the 116th Congress began last year, the average age of the Senators was just shy of 63. There are seven members on the far side of 80, including its oldest member, 88-year-old Dianne Feinstein.

Which brings us to a second secret that seldom stays quiet: once a dam breaks, the flood in Washington comes quickly and with little mercy. And yesterday, the Hoover Dam of Senate decorum came crashing down the Colorado River, sweeping away the civilized silence around Feinstein.

Feinstein’s hometown newspaper, The San Francisco Chronicle, published on Thursday a damning report about her reputation and perceived shortcomings in her job, which she has held since 1992. Based on public events and anonymous sources, including three of Feinstein’s Democratic colleagues in Congress, the newspaper describes a series of incidents that suggest the veteran politician is, at best, a beat slower than she was in her younger, trailblazing years. At its worst, the story casts Feinstein as an aged woman well past her prime, so much so that Senators now preemptively introduce themselves to Feinstein to spare her the awkward moment of having to ask their identities.

Once it becomes open season on a story like this one, everyone seems eager to chime in, rushing out from their silence or whisper campaigns onto the public square to shout stories that confirm the initial crack. It’s hard to imagine now that it was a non-story when Sen. Dick Durbin of Illinois—age 77—took over the Judiciary Committee in 2020 instead of Feinstein; no one then wanted to insult its top Democrat when she was quietly deposed. But D.C. can become a vicious den.

Feinstein declined to be interviewed for the story, but she couldn’t stop it from ricocheting around the Beltway. On Thursday, other news organizations were either repeating The Chronicle’s anecdotes or adding their own. By nightfall, Feinstein had called The Chronicle’s editorial board, defended herself, and declared that she would serve at least until her term ends in 2025, at which point, she will be 91 years old. She has already filed the paperwork to run again in 2024, a mostly performative act that lets her to continue meager fundraising.

But Washington, in its own perverse way, often rewards longevity. Since the mid-twentieth century, the Senate’s pro tem role has been passed to the most senior member of the majority party. If Democrats can defend their majority this fall, that role would pass to Feinstein next year after 82-year-old Sen. Pat Leahy of Vermont retires. Or, if Republicans are able to pick up a seat, while defending their incumbent ones, the role as third-in-line-to-the-presidency would fall to 89-year-old Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa. He would come behind Vice President Kamala Harris and 82-year-old House Speaker Nancy Pelosi in the line of succession. (Though Pelosi may lose the gavel after this fall’s elections.)

Put simply: the longer someone stays in Washington, the more difficult it is for them to leave. If they wait long enough, they’re literally heartbeats away from the White House. Some simply refuse to exit. No one can credibly argue that Sen. Robert Byrd, Sen. Strom Thurmond, or Sen. Thad Cochran were writing their best chapters by the end of their services. (For an absolute scorcher on Cochran’s ability, read Molly Ball’s legendary profile written at The Atlantic before she joined TIME.) Few are rushing to hire these once-high-octane octogenarians as lobbyists. The lawmakers who didn’t cash out in their prime for jobs on K Street face uneasy retirements out of public life.

Which brings up one final Washington secret that everyone knows: women are held to a different standard. Byrd, a West Virginia Democrat and the Senate pro tem, died in office at age 100; by the end, he was voting with simple hand signals. Thurmond, too, retired just a year before his death, at 100. While not always on the right side of history, he mostly got a pass for his evidently declining capacity at the end of his term. As The New Yorker quoted a former Senate aide in 2020: “For his last ten years, Strom Thurmond didn’t know if he was on foot or on horseback.” He, too, died in the pro tem role but received a hero’s funeral.

And a 2007 Politico story on Cochran, under the headline “Frail and Disoriented, Cochran Says He’s Not Retiring,” had this as the second paragraph: “The 79-year-old Cochran appeared frail and at times disoriented during a brief hallway interview on Wednesday. He was unable to answer whether he would remain chairman of the Appropriations Committee, and at one point, needed a staffer to remind him where the Senate chamber is located.” Cochran retired mid-term at age 80, and died a year later.

But Feinstein? If the scenes as reported by The Chronicle and others are accurate—and not even Feinstein’s fiercest defenders are denying them—they come at an uncomfortable time. There have been enough public moments of her making mistakes to merit the reporting, such as repeating the same question verbatim at a hearing, delivering a eulogy for a decades-long friend without mentioning the deceased’s name, and praising the Judiciary Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham, a Republican, for running “one of the best set of hearings that I’ve participated in” for Justice Amy Coney Barrett—an assessment that sent Democrats groaning.

The Chronicle story concludes that “it appears she can no longer fulfill her job duties without her staff doing much of the work required to represent the nearly 40 million people of California.” In an accompanying editorial, the paper urges her Democratic colleagues to force the conversation. That may be appropriate, while not necessarily feeling fair. It’s worth remembering that Feinstein’s aging male colleagues were mostly allowed to leave the Senate on their terms.

For instance, Sen. Johnny Isakson had been serving in the Senate with Parkinson’s Disease, and no one seriously pushed him to leave against his will. The Georgia Republican’s health remained his news to discuss when he was ready. He didn’t disclose his diagnosis for two and a half years, in 2015.

Arizona Sen. John McCain’s more public fight with brain cancer brought a national conversation about the disease. The same when Sen. Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts died a decade earlier from the same hellish brain cancer. But when Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died in 2020 at age 87, it didn’t take long for liberals to rage that she should have retired when a Democrat held the White House so they didn’t lose the seat to a conservative.

No one on the Hill has so far denied that Feinstein has slowed down. She is no longer among the fiercest legislators on her side of the Capitol. So legendary is her tenacity that Annette Bening portrayed her in a film about Feinstein’s persistence in investigating the CIA’s enhanced interrogation programs and producing what is widely called “The Torture Report.” But rare is the 80-something today who has the same edge they had in the mid-2000s.

But it’s also true that seniority remains, for the most part, the unwritten law of the Senate; longevity begets privilege. But a juicy story opens the door for the pile-on, and no one on this side of the Atlantic understands schadenfreude better than Washington’s insiders. Yet those same clucking beaks would do well to remember that showing too much glee lands can land you one ill-worded observation away from acting like a sexist. In that, Feinstein and her backers still have power, even if the Senator herself doesn’t always remember to deploy it.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com