Death waits for no man—especially not a forensic pathologist.

On Christmas Eve, 2008, Dr. Werner Spitz received a call asking him to consult on the death of a 2-year-old girl. Spitz was on the next flight to Orlando. The task ahead was nothing new, but even amid a long career doing this work, some moments stay with him.

“I remember that to this very day. I walked into the funeral home, and here was this long, long hallway—unilluminated because by the time I got to Orlando, it was dark,” Spitz recalls. By 11 p.m. the funeral home was deserted, save for a gurney carrying stacks of boxes.

The skeletal remains inside belonged to a girl named Caylee Anthony. Her mother, Casey Anthony, had been indicted for her daughter’s murder, and Anthony’s defense lawyer was seeking a medical opinion. Spitz spent Christmas Eve examining the skull of the young victim. After finishing his work, he packed up and returned home to Michigan. It was not up to Spitz whether the mother was innocent or guilty; in a trial that would become national news, Casey Anthony was eventually acquitted on the murder and manslaughter charges she faced. All he could do was give his best account of how he thought the girl died—including his assessment that the evidence on the body did not confirm the state’s version of what had happened to Caylee—and leave the rest up to the lawyers, judge, and jury.

Spitz spent the next day opening gifts with his children and his 10 grandchildren. That kind of shift from grappling with violent death to enjoying the pleasures of daily life has always been part of his job, but that doesn’t make it easy. “It isn’t really a matter of it being hard for me to do it because I’ve done lots of such cases. But I then go home and go to sleep, and I dream about it, and it’s horrible,” he says.

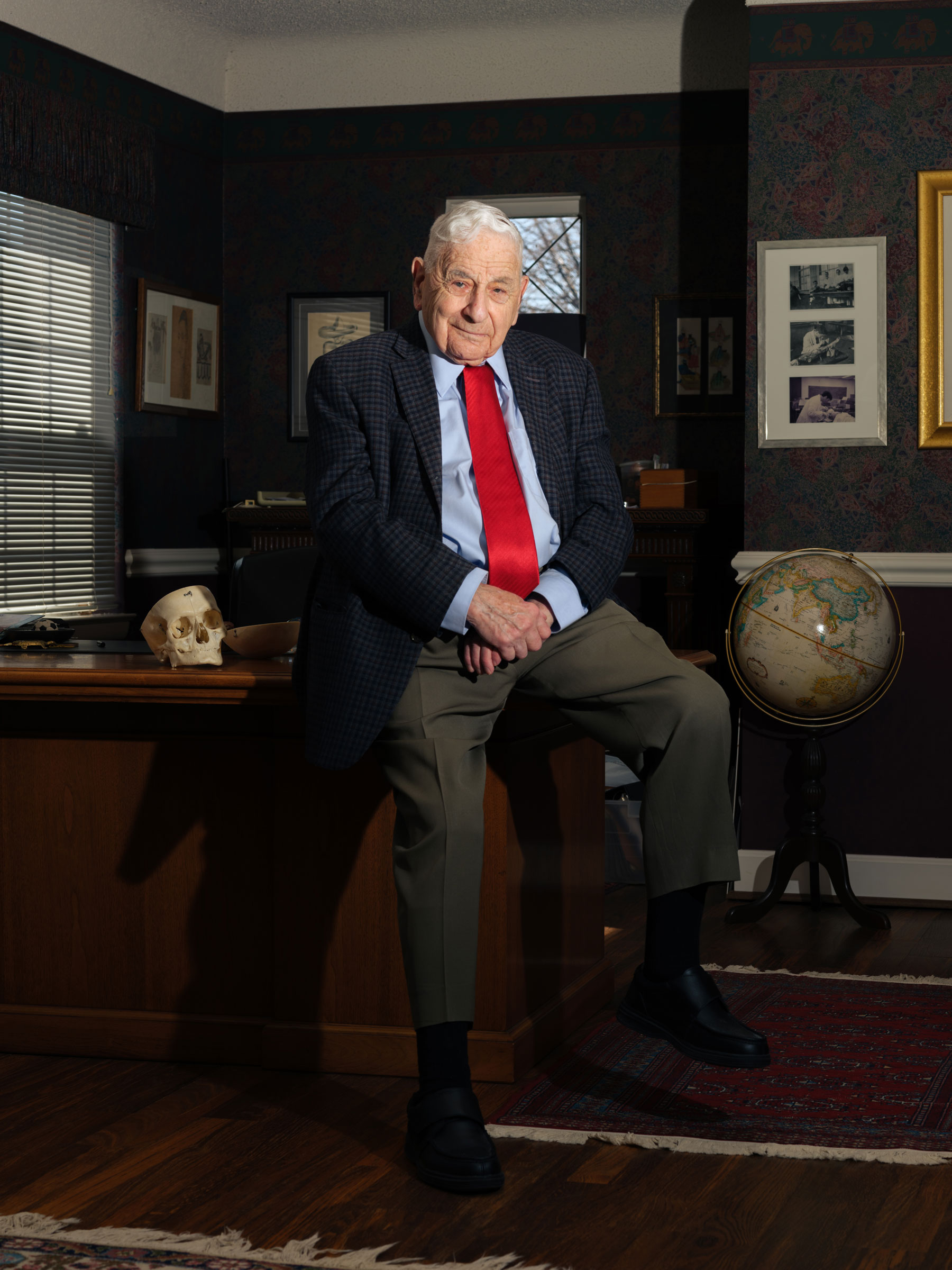

To the philosopher or the cleric, death is an enigmatic thing, but to the forensic pathologist—a doctor who deals in the traumatic injuries of violent deaths—it is a science requiring patience, time, and the proper tools. As a founding father of modern forensic pathology, Spitz has seen the discipline grow from its infancy, and he himself wrote the book considered the gold standard in the field today. Lawyers, judges, and police may be the most familiar players in the justice system, but it is the doctors like Spitz, shuttling from town to town with his medical supplies, who do the science required to solve crimes. Even if a murder goes unseen, the body bears witness. And the bodies that Spitz has been tasked with interpreting have shaped the course of American history.

Read more: It Might Be Impossible to Get Away With Crime Some Day

At 95 years old, with more than six decades of expertise under his belt, Spitz has played a role in a long list of famous cases: the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr.; trials involving O.J. Simpson, Phil Spector, and the “Night Stalker” Richard Ramirez; the killing of JonBenet Ramsey. He’s conducted thousands of autopsies, and he has no interest in retirement. (Golf bores him, he says.) He’d much rather spend his days looking for the small clue—an abrasion, a tiny puncture in the skin, an impacted skull—that solves a mysterious death.

“It’s like being a medical detective,” says Spitz. To him, a gunshot wound is not a hole in the body: it’s an event that leaves all manner of evidence, from metal fragments and broken vertebrae to clothing fibers and contusions. As Spitz explains: “The bullet doesn’t tell you anything. The skin tells you.”

Spitz has never been a stranger to death. A German-born Jew, his parents shipped him off to Paris in 1933, the year that Hitler became chancellor, to live with an aunt until they could get settled in what was then Palestine. “My mother realized that we better get out of here before it’s too late,” he says.

Both of his parents were doctors, and Spitz followed in their footsteps, attending medical school in Geneva and then in Israel. His first introduction to what would become his specialty began as a punishment. To keep Spitz away from friends his father deemed “mischief-makers,” he was sent to shadow the city hospital chief in Tel Aviv in the department of pathology every summer. The examiner carried out autopsies for police investigations, and Spitz was fascinated. “I went to watch autopsies, every single autopsy that occurred,” he recalls.

In the seven years he worked in Israel after becoming a doctor himself, however, he was tasked with examining only one murder. In a case that sounds like a bizarre movie plot, the murderer and his victim were both bagel vendors in a bus depot. When one vendor hiked up his prices, the other one stabbed him to death. There wasn’t much to solve, as the crime had taken place in public, and the perpetrator, motive, and means were all clear. Still, this case was a turning point because it made Spitz want to go somewhere with more challenging murders to study: He began to look for a way to the U.S. He doesn’t smile at death, but he can’t help but chuckle at the fact that a change in bagel prices would take him out of the Tel Aviv morgue and set him on a new path.

Read more: Can Specks of Dust Help Solve Crimes?

Coincidence, in retrospect, can seem like destiny. So it was that Dr. Spitz happened to be traveling by ship for a job in the Maryland medical examiner’s office in November 1963. The night before the ship was meant to dock in New York Harbor, it was halted 100 miles off the coast because of a national emergency: President Kennedy had been assassinated. Shock and confusion settled across the passengers, stunned by the president’s murder. “It was a ship with many decks, and I walked around everywhere, and everywhere there were collections of people listening to shortwave radios that would tell what happened. Everybody was speculating,” he says. “It was a terrible experience. The ship was all dark: there was no light, no music, no dancing, no nothing.”

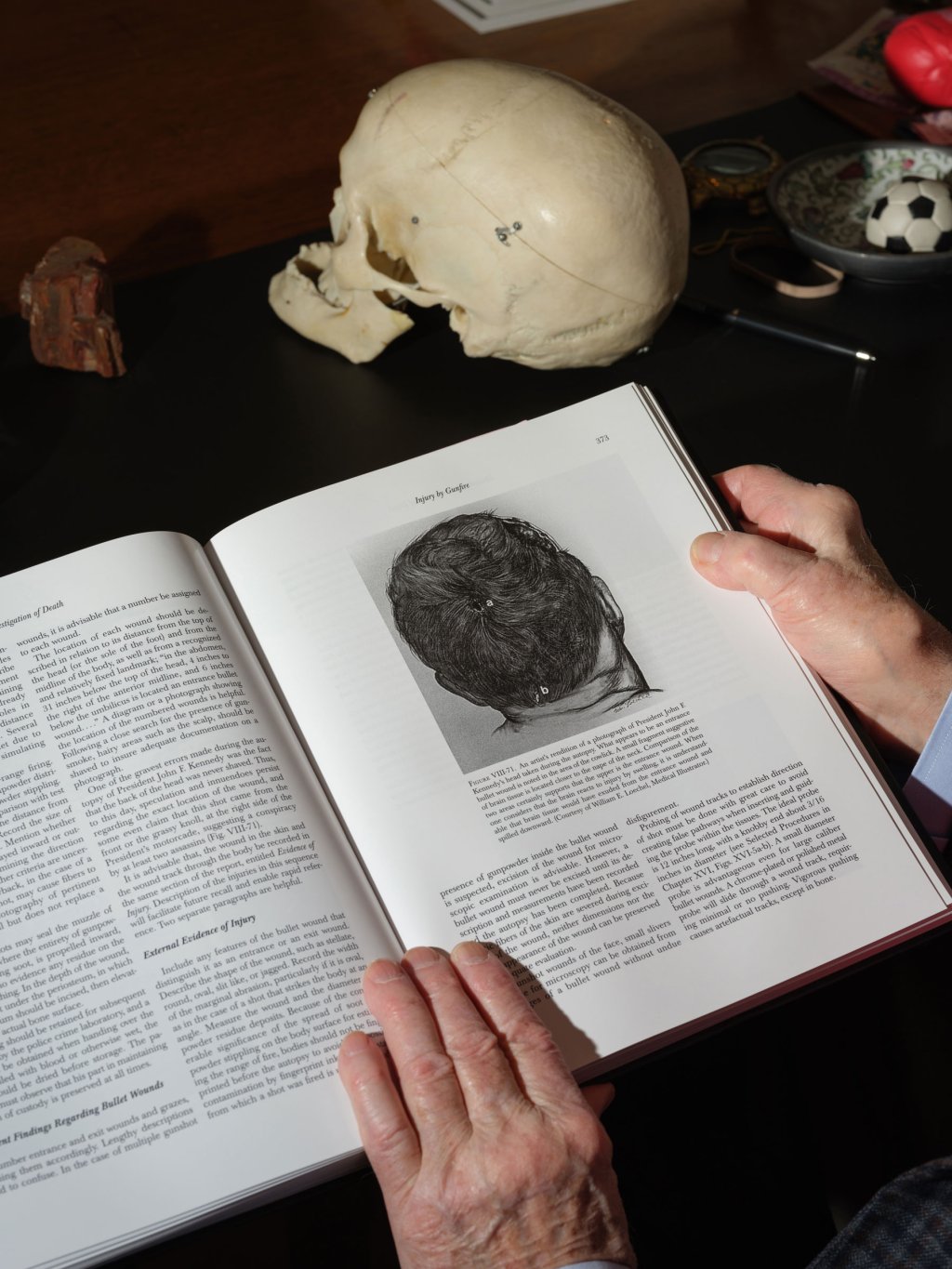

Little did he know, Spitz would be the one to dispel much of the speculation that sprung up around Kennedy’s assassination. Over the course of the next decade, Spitz became an expert in his field, teaching at Johns Hopkins University and eventually being named the chief medical examiner of Wayne County in Michigan. In the 1970s, a government committee called him to reexamine the autopsy performed after Kennedy’s assassination. “At that time, the knowledge of forensic pathology was at its bottom,” Spitz said of the 1960s. “People looked upon a gunshot wound like a hole in the skin. But it’s not a hole in the skin! Absolutely not.”

In Washington, D.C., Spitz sifted through all the evidence—the autopsy report, the clothes Kennedy had been wearing, enormous color photographs of the cadaver. “I could see every pore in the President’s face,” he recalls. The errors in the autopsy were so numerous, according to Spitz, that he went so far as to call the procedure “botched.” To a veteran forensic pathologist, one error stuck out in particular. The doctors had mistaken an exit wound for an entrance wound in the shot that hit Kennedy in the neck. To Spitz, however, the evidence was clear. The direction of the broken skin and even the fibers from his clothing pointed outward.

By identifying the puncture in Kennedy’s throat as an exit wound, Spitz was able to dispel one of the most prevalent conspiracies: the “grassy knoll” theory, or the idea that there was a second shooter, in front of the President, in addition to Lee Harvey Oswald who was behind him.

“In both the President and in Martin Luther King’s case, the mistakes were made by people who have a rank in society that enables them to offer opinions,” Spitz said. “But they were wrong.” Called to reexamine the findings in King’s assassination, Spitz uncovered similar such mistakes. King, who had been shot from across the street while standing on his balcony, was found with tiny grains of dust or sand embedded in his face. Examiners mistook this substance for gunpowder, meaning that he would have been shot in the face at close range. By disproving the existence of gunpowder, Spitz was able to confirm the cause of death as a long-range shot.

While some of these findings might seem logical with hindsight, they were far from obvious at the time. Forensics in the U.S. was often junk science. Forensic pathology was first recognized in the U.S. in 1959, when the American Board of Pathology began certifying doctors in the specialty. Prior to this period, forced confessions or witness testimony were frequently all that murder investigations had to go on; today, researchers have shown that such testimony is noteworthily unreliable. The hard evidence that law enforcement did collect was often based on pseudoscience such as anthropometry. Detection of gunshot residue began to become accessible in the 1970s, and police forces were still years away from solving crimes with the assistance of DNA evidence. Spitz, thanks to his training abroad—where forensic pathology was more advanced—supplied much needed expertise.

The field advanced swiftly in the following decades, but Spitz’s talent sometimes seems to go beyond his knowledge of the science involved. Diane Lucke has been Spitz’s right hand since the 1970s, beginning work as his phono-typist and going on to assist him in many cases. Lucke recounts one investigation in 1990 of a nurse who was found dismembered, her remains distributed among multiple trash bags. Spitz was able to locate a tiny skull fracture that he determined as the cause of death. On his suggestion, the police searched her ex-husband’s house, located a receipt from a hardware store and identified his purchase: a wood-splitting wedge. “It fit perfectly into the wound, into the injury in the skull,” Lucke said. “A number of people wouldn’t have even paid attention to that or wouldn’t have observed it in all this mess, because the body was so badly decomposed.” The ex-husband was convicted.

Read more: New Analysis Reveals How King Richard III Died

Such a discovery can seem like the stuff of a mystery novel, with Sherlock Holmes uncovering the truth in the nick of time. It might be why the public sometimes looks upon forensic pathologists as oracles, believing them capable of reconstructing ironclad, Clue-like scenarios. Despite the enormous advances of the discipline, it is far from a perfect science. Even seemingly unassailable evidence such as DNA has been demonstrated to be fallible. And medical examiners can be affected by prejudice, including racial basis. As expert witnesses, they can also earn big money—as much as $5,000 a day, according to some reports. And Spitz himself has come in for criticism over the years: JonBenet Ramsey’s brother sued him for defamation, though he later dropped the lawsuit. Nor is Spitz always on the side of the victim. Spitz insists that whether he’s contracted by the defense or the prosecution, he can’t be bought. For instance, after being hired by the defense for Michael Peterson, the so-called “staircase killer,” Spitz was not called to the stand because his medical opinion was deemed damaging to the defense. (Peterson was convicted.)

“An expert witness needs to be courageous when it comes time and to say he doesn’t know the answer,” Spitz tells me. “He must say openly, ‘You know, Your Honor, I’m sorry, but I do not have another opinion than the one I gave.’ Or say ‘I don’t know what the answer is.’ We do not know everything. We know a lot, but we don’t know everything.”

Spitz is compelling in the witness box: Like a modern-day Shakespeare character, he once took a human skull out of a tote bag to make a point. When testifying in the civil case against O.J. Simpson, he was unequivocal, describing the blow that killed Nicole Brown Simpson as a “devastating slash” that “[cut the] voice box in two, entering the bone of the vertebral column.” He speaks with an accent somewhere between German and Israeli, discussing stab wounds and leaky brain matter with an ease that comes from dealing in death for nearly three quarters of a century.

Dr. Henry Lee, a forensic scientist who has worked on many cases with Spitz—including those of Michael Peterson, JonBenet Ramsey, and Phil Spector—compared their work to that of a small part in a big symphony. “In a symphony, you have the director, you have the musicians. We’re just a musical instrument,” Lee says. “Just like a symphony, the audience decides to like this piece of music or not. It’s not the musical instrument. Whether a jury finds someone guilty or not, that’s not up to us.”

At the same time, Spitz seems keenly aware of the responsibility in his hands, whether in the morgue or on the witness stand, and it’s what continues to motivate him in his seventh decade on the job. Lucke, his assistant, remembers one of the largest-scale cases they were involved in: the 1987 crash of Northwest flight 255. The plane clipped a light pole during takeoff from Detroit, crashing moments later and skidding onto a nearby highway, killing everyone onboard (save for a 4-year-old girl whose miraculous survival is still a mystery to doctors), in addition to several motorists. Given the impact of the crash, only a few of the 156 victims were visually recognizable; the rest needed to be identified by dental records or fingerprints. Both Spitz and Lucke had years of experience by that time, but this case was exceptional; entire families had been annihilated in a matter of minutes. Some parents looking to Spitz to identify remains had lost two or three children in that crash.

The crash site was a short drive from their homes, but it looked like a war zone, with debris and human remains strewn across the road. The pair set up a makeshift morgue in an airplane hangar, with sawhorses instead of medical tables. “It got to the point where he sent me out with the families, and he went back in with the bodies, because he was crying with the families,” Lucke recalls. Spitz is not immune to the suffering that surrounds his work. It’s something he thinks and talks about a lot: Was this person in pain? Was he aware he was about to die? Beyond the legal ramifications, the answers to those questions are often the first things a victim’s family wants to know. It’s why he has an easier time dealing with dead bodies than with living victims. He explains it to me this way: the bodies aren’t suffering any more. What has happened to them is over. Post-mortem, Spitz can give their families perhaps not something as pat as closure, but at least answers about someone’s final moments.

“I’ve seen a lot, because of my age,” he says. “I’m still working because I enjoy the work. Because I like the work. Because with time, you have a new or a broadened ability to see things that in early life you did not see. You learn by exposure to things that, at one point you didn’t understand, and later on in life, you do.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com