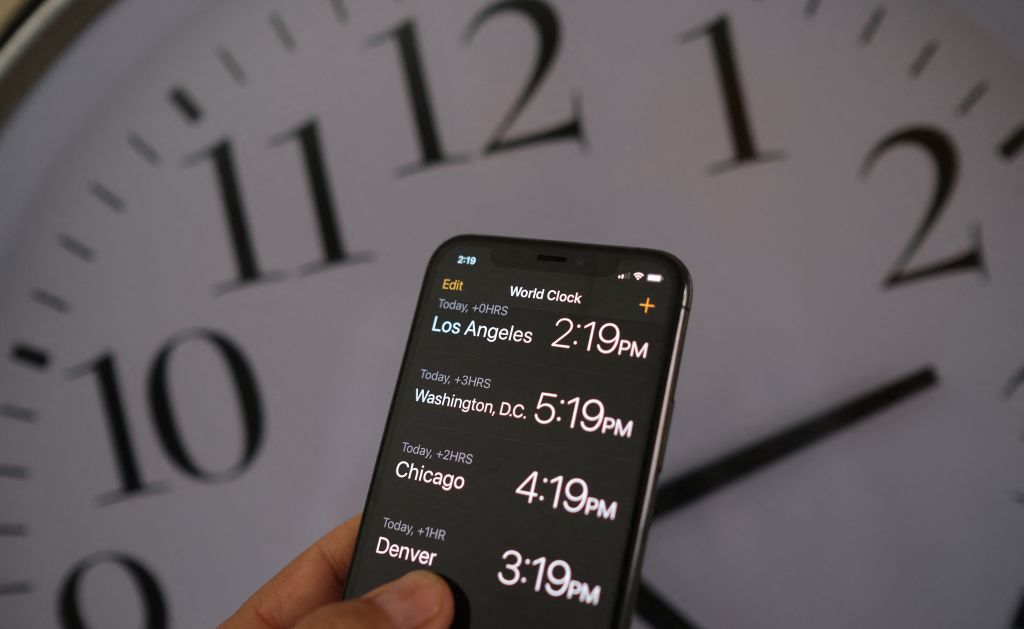

On Tuesday afternoon, just two days after Americans set their clocks forward an hour for Daylight Saving Time, the U.S. Senate passed a bill that would make Daylight Saving Time permanent, so that Americans wouldn’t have to turn their clocks back an hour. The overall effect of such a change would be that, in the winter when days are shorter, the extra darkness would shift toward the morning; rather than the sun setting in the middle of the afternoon in some places, it would rise later in the day.

“[T]his past weekend, we all went through that biannual ritual of changing the clock back and forth, and the disruption that comes with it. And one has to ask themselves after a while, ‘Why do we keep doing it? Why are we doing this?'” Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL), a sponsor of the bill, said on the Senate floor.

But if the House of Representatives passes the bill and President Biden signs it, it would not be the first time that the U.S. has tried permanent Daylight Saving Time.

“Daylight Saving Time has always been controversial,” says David Prerau, author of Seize the Daylight: The Curious and Contentious Story of Daylight Saving Time.

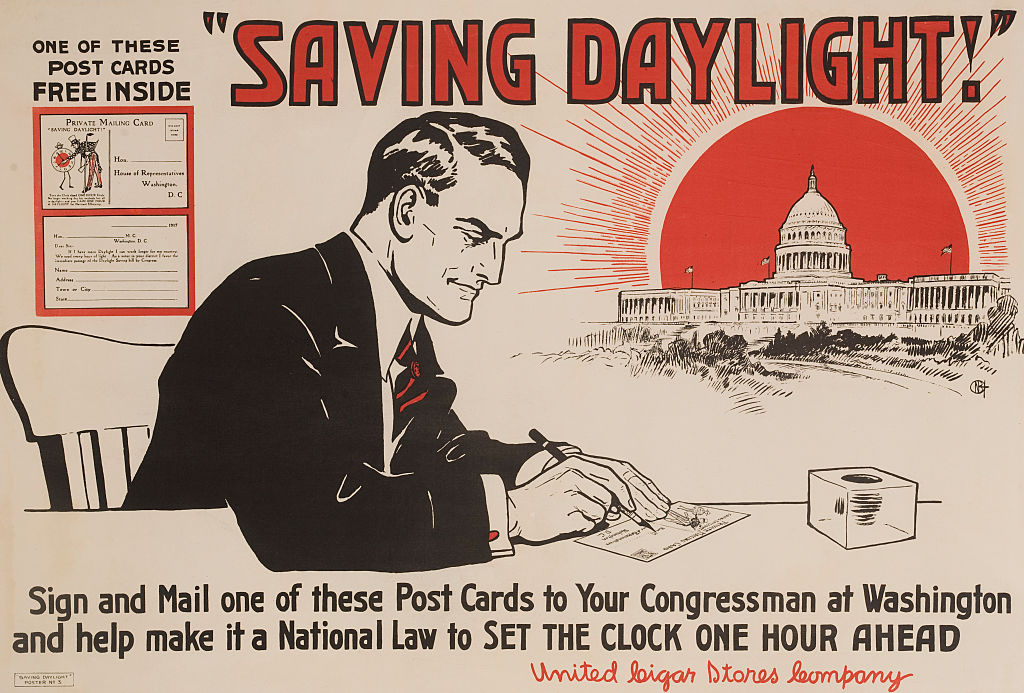

Daylight Saving Time was introduced in the U.S. as a fuel conservation effort in the World War I era, and the U.S. adopted a year-round Daylight Saving Time policy during World War II for similar reasons. The idea was that Americans wouldn’t have to turn on their lights so early in the day, and thus would save energy. But businesses reaped the benefits in peacetime too. Stores liked the extra hour of shopping in extended daylight, while sports and recreation industries liked that it allowed for later start times of games, boosting attendance. In 1966, the Uniform Time Act made it U.S. policy to observe six months of Daylight Saving Time and six months of Standard Time; it was an effort to get states on the same page, whereas before, cities and counties chose whether or not to opt out of observing Daylight Saving Time.

In December 1973, amid an energy crisis, President Nixon signed into law a bill for year-round Daylight Saving Time as one way to reduce the nation’s energy consumption. TIME reported back then that the hope was that “setting clocks ahead one hour could reduce nighttime electrical use and shave about 2% off the nation’s demand for energy.”

Read more: The Real Reason Why Daylight Saving Time Is a Thing

As Nixon described his rationale for signing the bill into law in a Dec. 15, 1973, statement, “We have taken a number of actions to meet the energy crisis, and more will have to be taken. Many require inconvenience and sacrifice. But Daylight Saving Time on a year-round basis, which will result in the conservation during the winter months of an estimated equivalent of 150,000 barrels of oil a day, will mean only a minimum of inconvenience and will involve equal participation by all.”

But the shift raised concerns soon as it took effect on Jan. 6, 1974. One was the safety of children walking to school in the morning, after eight children in Florida were involved in predawn car accidents in the wake of the time change, leading a TV commentator to coin the phrase “Daylight Disaster Time.” Reader letters to TIME provide a glimpse at the general opposition to the change. “Little children walking to school in the dark? No, mothers are driving them. This is saving energy?” Lynn Ward of St. Joseph, Mich., wrote. “No matter how Congress legislates, there are only a limited number of hours of daylight. We on the western edge of a time zone are using more electricity to cope with the extra hour of morning darkness than we did with the hour of evening darkness.” Perhaps referring to Watergate, the other crisis taking up Nixon’s energy at the time, Marianna Byg of Columbus, Ohio, joked, “the Nixon Administration has not seen the light for so long that it thinks it fitting for the rest of the population to be in the dark at least part of the time.”

The experiment was supposed to last for two years, but it only lasted eight months, and Congress reverted to standard time in the fall of 1974.

“We’ve already tried year-round Daylight Saving Time, and we found that it was very unpopular. So I would expect some of the same problems might happen again,” says Prerau.

The U.S. started observing seven months of Daylight Saving Time in 1986, and has been observing eight months from March to November since 2007. With each expansion, the rationale has always been, Prerau says, “to go as far as you could go without starting to have the negatives of late sunrises in the winter.”

The proposal that just passed the Senate would take effect in November 2023.

As for Prerau’s personal opinion on Daylight Saving Time, he prefers the current timeline for changing clocks.

“I personally think that the current system that we have is an excellent compromise, between having Daylight Saving Time most of the year, but eliminating all the negatives of Daylight Saving Time in the winter,” he explains. “For the saving of that one hour of sleep in March, [you’d be] getting four months of dark mornings and cold mornings in November through March. So that’s why I think the current system is better.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com