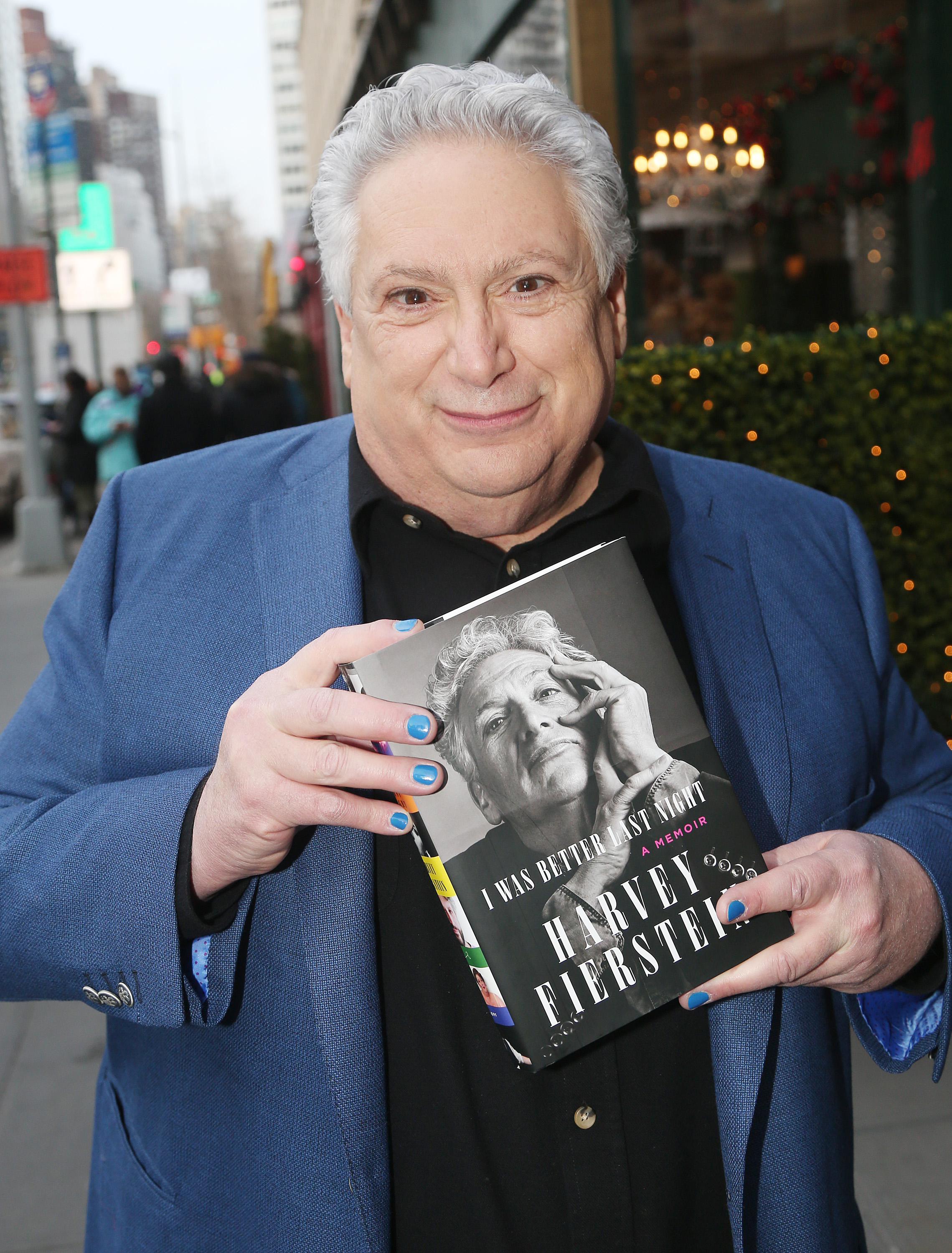

TIME: How do you know when you’re ready to write a memoir, I Was Better Last Night?

Fierstein: It’s very simple. This is good instruction for any of your readers: you arrange for a global pandemic. You clean your desk of all other garbage; then you look around the house for other things to do. I made five quilts. I walked the dog. And then the next thing—the only thing—I could possibly come up with, besides cleaning the refrigerator, which is nothing anybody ever wants to do, was to write my memoir.

It’s either that or cleaning out the basement.

So I did get to that first. You know, I’ve never written any prose of that length. I’ve never written a book; I don’t know that I ever would have written one if we weren’t in lockdown. I can tell you it’s very different. But in the end, it’s been thrilling, really thrilling.

You’ve said that many of your plays’ characters have embodied parts of yourself. I’m curious how different it was when it was just you, and also the whole you.

As a dramatist, you try as hard as you can to leave yourself out of the equation and let the character speak. When you hear the author’s voice, you’re being cheated. So it’s very different to all of a sudden sit down and engage with that voice; I would say the experience was much more like having a really good conversation with a friend. I was trying very hard to have it feel like sitting with me; to make sure it was me you were hearing. The other thing I tried to do—and I hope I accomplished is—is that I tried not to judge myself. I’ve tried to leave that up to my audience.

Do you like to gossip?

Yes, but I do like to keep it just between me and my friends. Of course I do. You know, I’m in the theater! We do the same fucking shows eight times a week, we have nothing else to do. But there’s no real gossip in the book. There’s one story about an actress, for example, that I don’t name. A badly-behaved actress. Because it felt like, what was the point? If I hurt her back for hurting me, that makes me just as petty. And I didn’t want her to get anything out of it! I didn’t want to give her a platform to speak. In fact, I don’t even tell the story [of my experience] with a second badly-behaved actress because I couldn’t think of a way to tell that story without revealing who it was.

The real question with showbiz news is who’s feeding it to you? That’s the real gossip. With many stories that I read, I can tell exactly who made it up. And I laugh because I say, Oh, that was this press agent. Because it’s just not true. And I think we’ve gotten much worse at knowing what’s real news and what isn’t. People now listen to gossip as if that’s the truth, but they’ll read news in the newspaper and think it must be a lie.

How do you reckon with the time-old tradition of gossip columns and blind items as a vehicle for speculating on someone’s sexuality?

Well, the real history of gossip is that it was much less revealing who was gay, and more about hiding it. Gossip columnists were supposed to be doing the opposite! They’d make up these stories of people being straight, having girlfriends. I mean, people thought Liberace was straight!

And we all went through that terrible, terrible period of outing, which I loathe. But I also understood it. You had openly gay people losing their jobs left and right because of fear of AIDS—and people who were in the closet were just raking in the money by being in the closet and leaving the rest of us to die. They collected their checks while we did the hard work. That was a terrible situation. I don’t talk about a lot of that crap in the book, but I did, I think, put in one sentence where I said, fuck them. And I still do have that anger, but I also have sadness for them. Because I know a lot of those people, and I know that they are cowards.

You wrote about rehearsals for the Torch Song Trilogy, and a scene specifically where Estelle Getty took issue with a line from her character, when she tells her son, “It gets better.” She’s talking specifically about grief, but that phrase has become such a rallying cry for the LGBTQ community more broadly—and maybe too generally—in recent years. Do you think that’s been the case?

Whatever you survive becomes a triumph, right? And I think time, you know, does make things better. Does it bring somebody back to life? No. But makes it easier to take that breath without that incredible pain underneath. Do things get better politically just because time passes? No. You actually have to do the work. One thing that people don’t understand, and I don’t understand why they don’t understand, is that you can’t go backwards. Nothing goes backwards! If you want to go backwards in time, you’re just kidding yourself. Especially these days when you see this ‘Make America Great Again’ idiocy; I look at those people and what I see are these walking skeletons. Dead people. They’re not looking to the future, and if you’re not looking to the future you’re not alive. You are saying, I am no longer a force in the world. I am just a memory. And that’s no way to live.

Speaking of Estelle Getty, I think it’s fair to say the world is a lesser place without your landing a cameo on The Golden Girls.

No. I worked for the same company when I was doing Daddy’s Girls with Dudley Moore, and I hung out there. There was some discussion of me playing Bea Arthur’s son, but I think Bea thought I was way too old. I had my own relationship with Bea, and we were friends. But the part was never offered to me.

Read more: These Rarely Seen Photos of Early Pride Parades Capture a Shifting Movement

You’ve long been at the forefront, or in the public eye, as an activist and a leader in the gay rights movement. Looking at the community today, do you ever think that the movement has left you behind?

First of all, I never thought of myself as a leader. You can’t really have leaders for a group of people who are all so different. We should be celebrating the fact that we’re all different. But I can give you a great example—years ago, I remember showing up to the Pride Parade, as I always do. It was one of the years that we started at Central Park and walked downtown; I looked over at the fountain and there was this group calling itself “Marriage Equality.” They were standing there performing gay marriages. And I thought to myself, with all the problems we have, you want a goddamn wedding cake? This is what you think we should be fighting for? And then I stopped myself. And I said, wait a second Harvey, look at them. They’re young people. This is their cause. Maybe they know something you don’t?

The future is always defined by young people, and those of us who are old—granted, I was maybe 35 at the time—owe young people all our support. What they think the movement should be, I’m going to get behind that. And God dammit, they turned out to be right.

You write movingly about body dysmorphia; about your relationship with your gender and drag. Over time, do you feel you’ve come to terms with your body and identity?

I haven’t. I’m no clearer on any of that than I was when I was four years old. Because I do what I do, and because I’ve done so much drag, I’ve found a place to put ‘it.’ I’m very comfortable being a boy most of the time; being a girl is a lot of work. When I played Edna Turnblad in Hairspray, and I was in that armor of Edna with the gorgeous wig, the heels, those big rubber tits—which probably weighed 25 pounds—I was in heaven. I don’t think I’ve ever been happier in my life. Backstage everyone called me Mama. I loved being Mama. Still to this day, the cast call me Mama when I see them. Six months after I left Hairspray, I went and did Fiddler on the Roof; I grew my own beard and played the father of five girls. Those girls called me Papa, and the cast called me Papa. I don’t think I’ve ever been happier in my life. There was no difference to me between those two experiences. Did I feel I was more one than the other? I don’t know. I don’t care. They both brought me incredible joy.

When I was a kid and growing up and coming out of the closet, I would meet older gay people and they would say to me, you know, we didn’t have it this good. They would say, I don’t know what my life would have been like, had we had this. I now understand what they’re talking about. But would I trade it for being young now? No, no, I had my adventure.

You wrote in the book’s preface that memoir-writing is all about looking back. But what are you looking forward to?

I don’t spend a lot of time looking back. There are a couple of projects that, you know, I’d love to get another crack at—but I consider that looking forward. Life is too much fun to sit around looking back.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Alex Rees at alex.rees@time.com