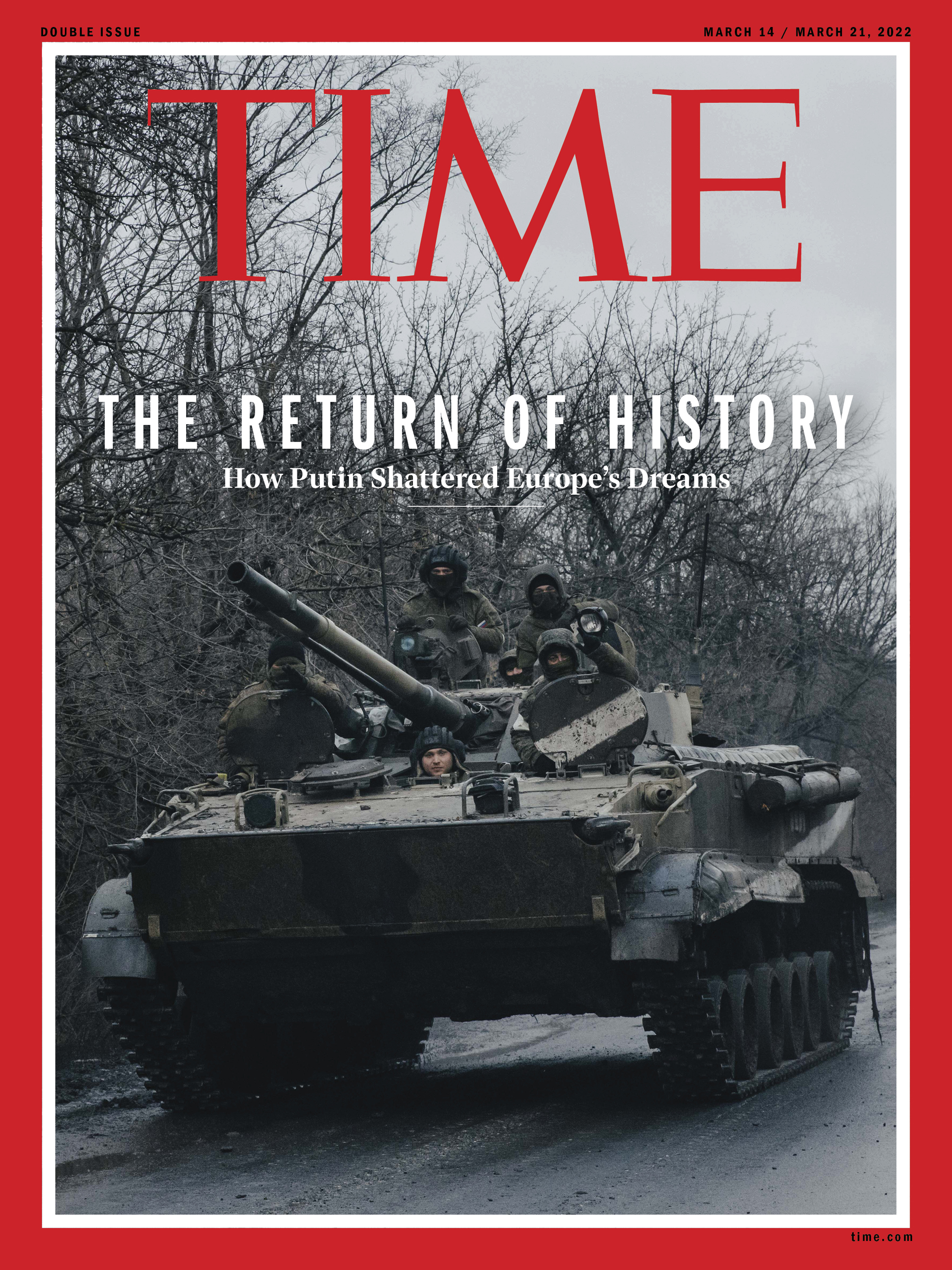

On Wednesday, Vladimir Putin declared war on Ukraine with tanks, rockets, and a slap to the face.

The optics of the President of Russia, a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council, announcing the invasion of a sovereign nation during an emergency meeting of its members—presided over by Russia’s U.N. ambassador, no less—were stark: the ultimate repudiation of the rules-based world order that the organization embodies.

U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres was shocked enough to call it the “saddest moment in my tenure.” Though as the bombardment of Ukrainian cities escalated alongside the testiness of exchanges inside the chamber, feelings shifted to outrage at the impotence of members’ calls for peace and dialogue.

Read More: Here’s What We Know So Far About Russia’s Assault on Ukraine

“At the exact time as we were gathered in the council seeking peace, Putin delivered a message of war in total disdain for the responsibility of this council,” said U.S. permanent representative Linda Thomas-Greenfield. “This is a grave emergency.”

It would be reductive to attribute these failings simply to Putin’s belligerence. It’s been an open secret that global governing institutions have been broken for a long time, spotlighted by a series of recent crises that have received limp attention: the annexation of Crimea, the COVID-19 pandemic, the return of the Taliban to power in Afghanistan, popular uprising in Kazakhstan, coup d’état in Myanmar, and now, most drastic of all, invasion of Ukraine.

“It’s the biggest crisis since World War II, in the [heart] of Europe, and will have huge consequences,” former Mongolian President Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj told TIME on Thursday. “It will require great effort to settle this issue and update the world order.”

If, and how, this can happen is the big question. The West assumed that following the Cold War, the world had changed forever. But for a little over a decade, liberal democracies have lost their clout as nondemocracies have become increasingly successful economically. Now the old fissures have returned.

“It seems that the old Cold War tensions never really went away,” former Thai Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva tells TIME. “It’s almost as if we’re back to a situation of war and potential flash points around the world.”

On Wednesday, the Biden Administration called out Beijing for its role underwriting this shift. “Russia and [China] also want a world order,” U.S. State Department spokesman Ned Price told reporters. “But this is an order that is and would be profoundly illiberal, an order that stands in contrast to the system that countries around the world … have built in the last seven decades.”

But partial blame must also be placed on the hubris of the U.S., which never strengthened international institutions in those 70 years when it was the only dominant power. The Bretton Woods institutions set out global economic rules around which we still operate, including the World Trade Organization, International Monetary Fund, and others, in terms of trade, commerce, and sanctions for noncompliance. Up until recently, because of the wealth of America and the potency of developed European nations, the West largely called the shots.

Read More: ‘We Will Defend Ourselves.’ Photographs of Ukraine Under Attack

Today, however, Washington finds itself unable to freely exert its will as a result of Beijing’s swelling economic and diplomatic clout. Tellingly, Chinese officials lead four of the 15 U.N. specialized agencies. In January, China was the only U.N. Security Council member to vote with Russia in a failed attempt to stop a U.S.-requested meeting regarding Moscow’s troop build-up at its border with Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Russia has stunningly co-opted the language of the U.N. Charter 2(4) regarding sovereignty and territorial integrity to justify its actions. “So it’s sort of claiming the mantelpiece of international order, while fundamentally and quite dramatically undermining it,” says Leslie Vinjamuri, dean of the Queen Elizabeth II Academy for Leadership in International Affairs at Chatham House.

The difference between Beijing and Moscow, says Rana Mitter, professor of the history and politics of modern China at Oxford University, is that the former wants to influence the international order to its own benefit from within, while the latter wants to tear it up entirely: “Because of the kind of state that China wants to be, that is globalized in terms of its trading capacity but able to be as self-sufficient as possible at home, the international order actually suits it very well.”

That makes it arguably a larger challenge for the West than even the Cold War, when the West was up against a country that was in military terms a superpower, but economically weak. With China, “all of a sudden we’re looking at a country that has the economic capability to take us all on,” says Iain Duncan Smith, an MP and former leader of the U.K. Conservative Party. “That means the rule-based order can be debauched, which is what’s happening now.”

Beijing supports international institutions and agreements aligned with its goals, such as the World Bank and the Paris climate pacts. But where Beijing’s interests diverge from established norms, especially human rights, it aims to corrupt those values and bring in alternative models. In fields where standards are yet to be established, like internet governance, Beijing works with Moscow and other illiberal nations to push standards that align with their interests. It can do so because those institutions in themselves are weak.

“The problem is that when we had a world order that was new and good, we never really stepped up in terms of getting the multilateral or international organizations to play a lead role,” says Abhisit.

Read More: Why Sanctions on Russia Won’t Work

China’s ambivalence on Putin’s aggression against Ukraine spotlights the new normal. While calling for “dialogue and negotiation” on Thursday, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi effectively gave his blessing to the invasion, telling his Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov, on a call that “the Chinese side understands Russia’s legitimate security concerns.”

“Beijing thinks this one’s probably going to bypass China, as it is a war between two European countries,” says Mitter. “And that the role of NATO and the United States is really what’s at the heart of the dispute.”

It’s wrong to think of inaction as completely new, though. In truth, the exceptional moments in U.N. history have been when consensus has been reached among the P5—the officially recognized nuclear-weapons states—to stand up for the international order when one of them was involved. “It just doesn’t happen,” says Vinjamuri. “So this [kind of Ukraine situation] isn’t really out of keeping; it’s built into the structure of the U.N.”

Much will depend on whether meaningful costs are inflicted on Putin. The U.S., E.U., U.K., Australia, Canada, and Japan have unveiled sanctions on Russian banks and wealthy cronies of Putin, while Germany halted certification of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia. However, China along with other Kremlin friends can likely compensate. Bilateral trade between China and Russia rose 33.6% year-on-year to some $140 billion in 2021. Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan was in Moscow on Wednesday to discuss, among other things, the $2.5 billion Pakistan Stream gas pipeline, which Moscow wants to build between Karachi and Kasur, expressing bewilderment at arriving during “so much excitement.”

So, is there any hope for the established world order? Rather than ripping up existing institutions, Abhisit says, there is a need to embolden them so that they can resolve these kinds of conflicts without it simply being left to the warring parties.

“The [Ukraine] situation has escalated due to pure mistrust,” he says. “Russia is uncomfortable with having NATO installed on its doorstep. Ukraine feels threatened. And the West is suspicious of Russian motives.” A meaningful discussion about the expansion of NATO and the sovereignty of Ukraine by a neutral party might have led to a more desirable outcome, he adds. “I don’t pretend it’s easy, but I can’t see that happening when it’s just being dealt with by the conflicting parties.”

Read More: The Russian Assault on Ukraine Poses Huge Risks for the Rest of Europe and the World

Suzanne Nossel, CEO of Penn America and a former Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for International Organizations under Barack Obama, has argued that states must be forced to go through a written public process every time they exercise a U.N. veto, so that their arguments become subject to the scrutiny of the international community, and that the U.N. General Assembly should be more empowered to act when the Security Council doesn’t.

Few would disagree that Wednesday was anything but a nadir for the U.N. and global governance writ large. “The international system, the U.N., is not really effective,” says Elbegdorj, who studied in Lviv, western Ukraine, for five years during the 1980s. “It’s just talking heads now, not really having any impact, and these forces [allied] with Putin know the situation.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com