Cool is the word used most often to describe her: the Coca-Colas and the cigarettes each morning, the leotard and the typewriter, the scotch and the shawl. California. Writing for the movies to make a living, making notes for the director, the short tight dispatches from the South and West.

But the word cool means the absence of strong feeling, and she was the opposite of that. I have a theatrical temperament, she once said. A wholly penetrable surface—one might also call her—that she then attempted to reshape into language that was capable of penetrating the rest of us.

There’s nothing one can write about Didion that’s not already been written, that she wouldn’t or did not already write better herself.

Read More: ‘My Wine Bills Have Gone Down.’ How Joan Didion Is Weathering the Pandemic

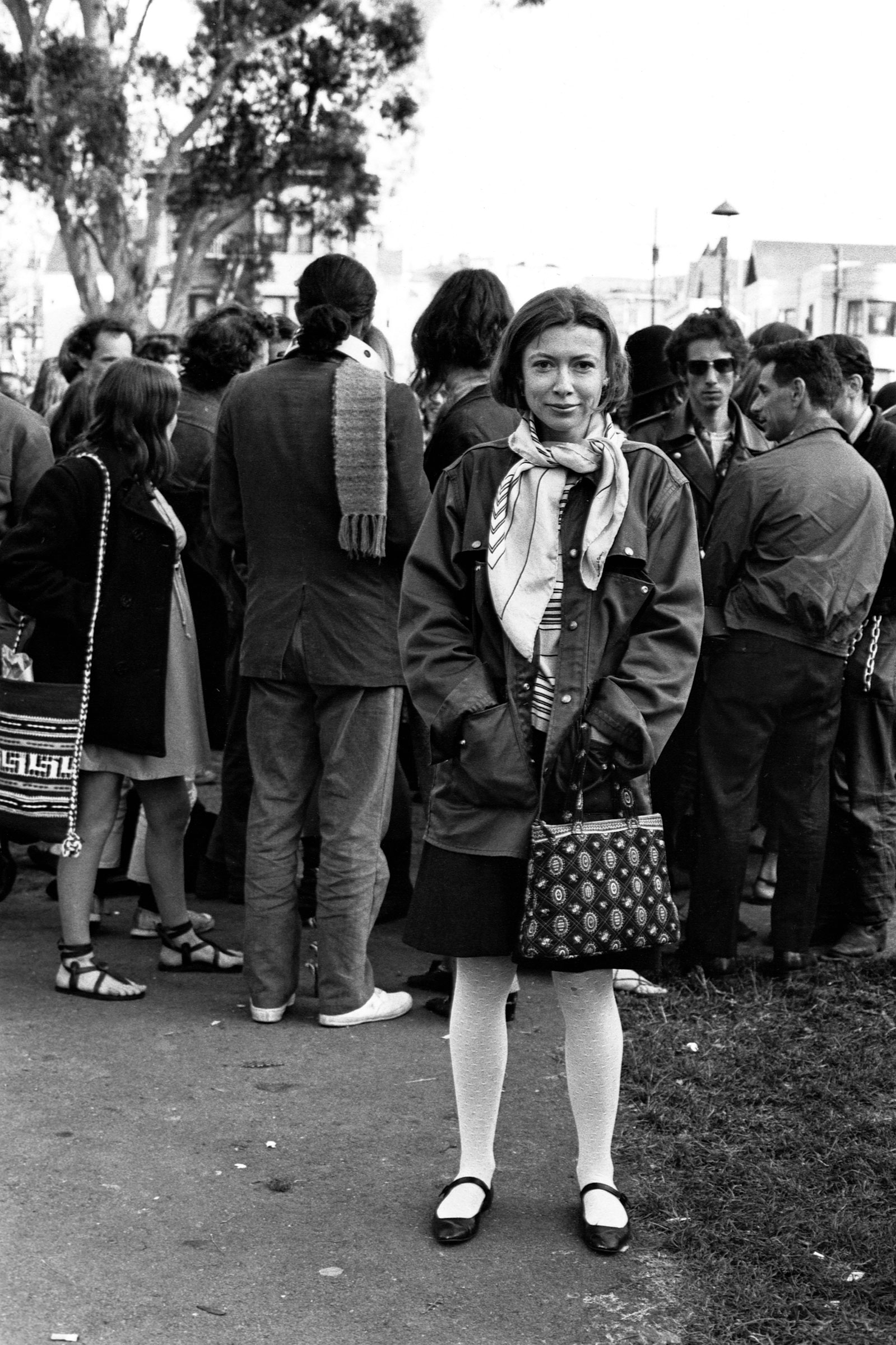

Her impossibly small stature: I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests. She sat in wait until the moment, its ruptures and its textures—not the story, but the life that lived beneath it—declared itself somehow. The 5-year-old in white lipstick, high on LSD, in Haight Ashbury in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”: The five-year-old’s name is Susan, and she tells me she is in High Kindergarten. She lives with her mother and some other people, just got over the measles, wants a bicycle for Christmas, and particularly likes Coca-Cola, ice cream, Marty in the Jefferson Airplane, Bob in the Grateful Dead, and the beach.

It was gold, she told Griffin Dunne, her nephew, in his documentary, The Center Will Not Hold, about her life.

There’s an idea around writing that we do it to make sense, to give shape, but staying free of the assumption that there’s sense to be made was one of Didion’s most astounding accomplishments. Is that 5-year-old O.K.? Should she have taken her home, or called somebody in? What to make of Didion’s psychological deterioration as described by her psychiatrist’s assessments in “The White Album”? How sick was she really? How much was it all just the world, seeping in?

Of course what that essay shows us is that those questions aren’t answerable; not even particularly interesting.

Why is this woman so sad? some critics lamented, but if you spend any time at all in the world Didion was observing, the question also arises, why weren’t they?

And that sad woman just kept writing. Through the death of her husband: Life changes in an instant; and then her daughter, 20 months later, at 39.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live. Whenever I hear that quote, I get prickly, defensive. The whole essay is about how stories are failing, how at various moments in most writers’ lives language feels slippery and useless, stories too sensical and coherent to have anything at all to do with the life we’re trying to hold. Even words begin to feel too blunt-force, so much less than what we might have hoped.

Read More: Joan Didion Wrote About Grief Like No One Else Could

But then Didion knew all of this. She taught it to us, shaped and reshaped observations and experience until we saw. She collided all the various contradictions built with other people’s stories—politicians, advertisers, movies—bastardized and broken with too much coarse and hazy language, and she helped us see it all more sharply, with the lacerating power that comes from never trying to make sense.

They called her cool because she abhorred sentiment–A preference for broad strokes, for the distortion and flattening of character, and for the reduction of events to narrative–was wary of any mythology that might somehow anesthetize one’s ability to touch or feel what might be actual or real. This is her main complaint about New York, not the city but the story that obscured it, both in “Sentimental Journeys” and, much earlier, in “Goodbye to All That.”

It is easy to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends. Here are two of my favorite versions of her origins: when she was 5 her mother told her to stop whining and to instead write a story, and so she wrote one, and then she never stopped; just before the end of her time at Berkeley, she won a story prize from Mademoiselle and gave up the trip to Paris that they offered to get right to work as guest fiction editor instead.

Most of her best books are made up of reportage accrued over years of trying to make a living. And then there are the grief memoirs, stunning and unflinching. Grief has no distance. Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life. Her best novel, Play It as It Lays, was her first; the rest aren’t particularly great. She was a Reagan Republican before she disavowed the party. She was truculent, sharp and distant.

A single line that stood alone in her Times obituary: she left no immediate survivors.

I’m not telling you to make the world better, because I don’t think that progress is necessarily part of the package, I’m just telling you to live in it. Not just to endure it, not just to suffer it, not just to pass through it, but to live in it. To look at it.

A place belongs forever to whoever claims it hardest, remembers it most obsessively, wrenches it from itself, shapes it, renders it so radically that he remakes it in his own image…

We are imperfect mortal beings, aware of that mortality even as we push it away, failed by our very complication, so wired that when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves. As we were. As we are no longer. As we will one day not be at all.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com