In 1987, Congressman Barney Frank, a Democrat from Massachusetts, made history when he told the Boston Globe, “If you ask the direct question: ‘Are you gay?’ The answer is yes. So what?”

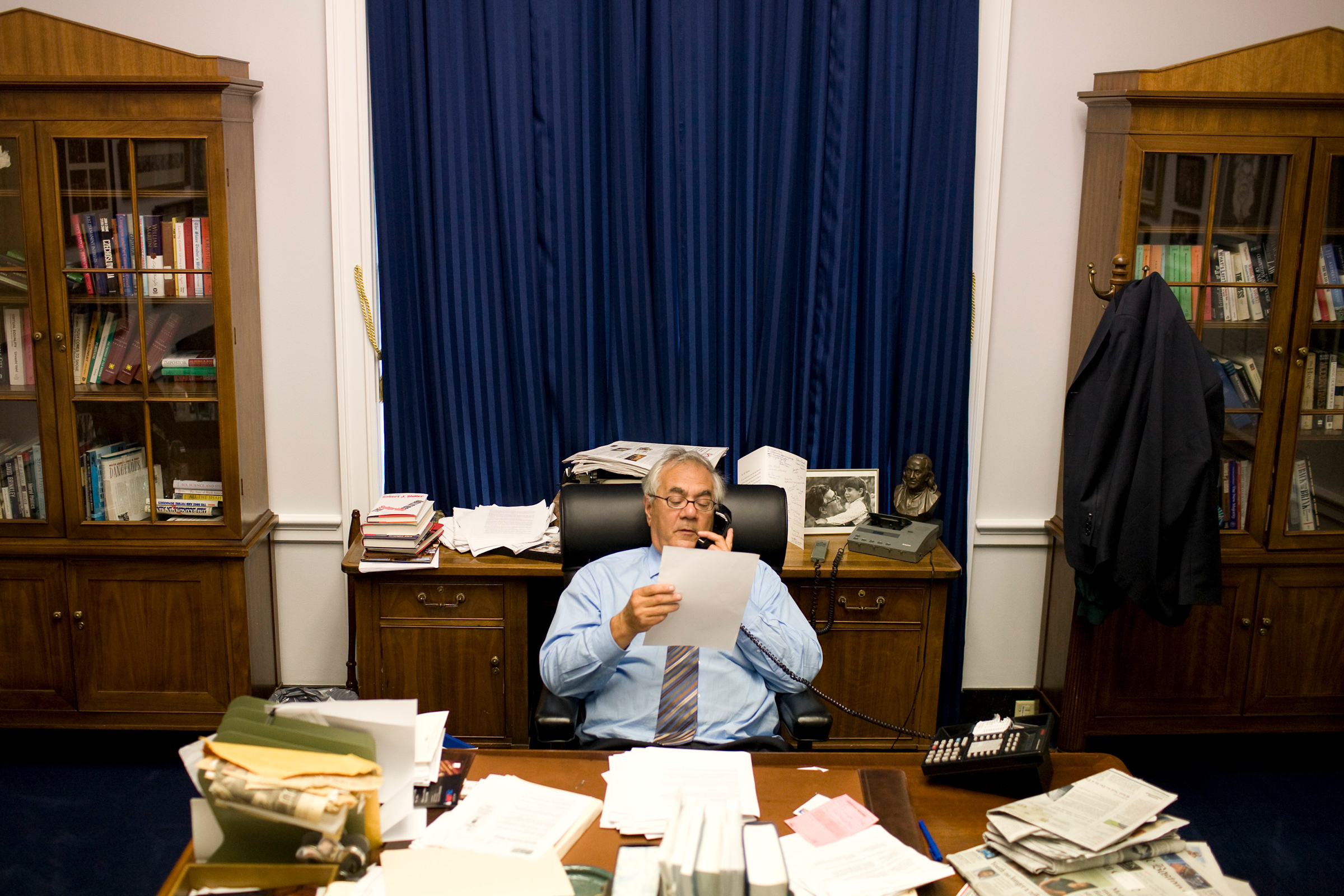

The interview made Frank the first member of Congress to choose to come out while in office, and propelled him into becoming one of the most prominent political faces of the LGBTQ rights movement in the following decades. During his thirty-two year tenure in the U.S House of Representatives, Frank advocated for numerous bills that promoted gay rights, and was the leading co-sponsor on other key legislation including 2010’s Dodd-Frank Act, which overhauled financial regulation in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. In 2012 he wed his long-time partner Jim Ready, becoming the first sitting member of Congress to enter into a same-sex marriage. Today he serves on the board of LGBTQ Loyalty, the world’s first exchange-traded fund that aims to promote LGBTQ rights.

Looking back for LGBTQ History Month, TIME spoke with Frank about his storied advocacy for LGBTQ rights in Congress, and the progress left to be made.

When you ran for Congress in 1980 you were not yet public about your sexual orientation. Looking back then, were you worried you’d be outed—and face consequences?

Very much so. I first started being involved in politics in the ‘50s when I was a teenager. I said, ‘Yeah, I’d like to get involved in politics, but I could probably never get elected because I’m gay.’ I knew I was gay from 13. And to get elected to office you’ve got to be popular. To be gay [was at the time] to be very unpopular.

My first run for public office was in 1972, in the [Massachusetts] state House. Everybody who ran for the legislature was asked by the gay and lesbian groups, ‘Would you support a gay rights bill, repealing the law against sodomy and preventing job discrimination?’ And I said yes, that I would support the bill and even be the sponsor. I did that assuming that I would be one of several people. But it turned out I was the only person that year who won and had said yes. [I decided then] that while I would not come out publicly, but I would be very supportive of gay rights. My principle is that you have a right to privacy, but not to hypocrisy.

Read more: Why Federal Laws Don’t Explicitly Ban Discrimination Against LGBT Americans

That was my position for the next eight years while I was in the legislature. Towards the end of that eight years, by ‘78 or so, I began to come out to friends and relatives—maybe a couple of dozen people. And to the then-leader of the gay rights movement in America, a guy name Steve Endean. He was disappointed, and I was disappointed that he was disappointed. He said, ‘Here’s the problem—I’m trying to get people to sponsor gay rights bills in all these legislatures, and I’ve been bragging about how many straight people I have supporting the bills. Every year I find out another one is gay.’

I had then decided by the end of the 1970s that I was going to retire [from politics] and come out publicly. I’d gone to law school, and I was going to become a practicing lawyer. And then the Pope intervened. Specifically, there was a Congressman from the district next to mine, who was a very liberal Jesuit priest. And Pope John Paul II ordered him not to run again. That created a vacancy. And I ran for it.

In 1987, you became the first Congressman to choose to publicly come out as gay. What motivated your decision?

I just couldn’t live anymore with the frustrations and emotional choking of trying to hide my private life—I couldn’t have a satisfactory private life. Everybody has emotional and physical needs that have to be expressed. When I went to Washington, I thought I could somehow find a way to have that emotional and physical outlet—without being public. And I couldn’t.

What was the response from your colleagues?

Surprisingly wonderful. Before I came out, it was not a great secret that I was gay. Understandably, gay people who knew I was going to come out were very enthused. But a number of my straight colleagues—maybe six or seven, [some of] the most liberal, most supportive of LGBT rights—came to me and said, ‘Please don’t do that. Yes, we want you to have a happy life. But you’re a very effective ally now on a whole range of causes.’ They were afraid that if I came out, my influence would be diminished in every area but in gay rights. And I couldn’t say that wasn’t true. I told them I hoped it wouldn’t be true.

So I came out and to my great surprise, it helped. Politically, people said ‘well, he’s being honest.’ It made me, frankly, more relaxed. Easier to be with. And it advanced my advocacy of gay rights. It’s one thing for me as a ‘straight person’ to ask my colleagues to vote for gay rights when they’d say it was politically difficult. It’s another when a colleague is asking you to do something deeply personal.

You mentioned this point earlier, but in the past you’ve promoted what some have referred to as the “Frank rule.”

The right to privacy does not include the right to hypocrisy.

Exactly. The idea that it can be appropriate to out closeted politicians if they’re taking actions that hurt LGBTQ people, do you still hold this position today?

Absolutely. And by the way, it’s not just with regard to LGBTQ rights. I think it’s been appropriate in the past when people have outed anti-abortion members of Congress who had facilitated their partner having an abortion. I think it’s a principle that applies across the board. If you’re an elected official, I do think you are morally obligated to obey every law that you vote for.

What was your proudest moment, in terms of your decades of LGBTQ rights advocacy while in office?

I’m going to have to pass on that. It just becomes—

Ready, in the background: “Marrying me!”

Well, that was the best one. That was good for me as well. Good for everybody else, but also good for me. If you go back to 2012, [same-sex] marriage was still very controversial. It was legal in Massachusetts, because of our state Supreme Court. But this is before the U.S. Supreme Court decided. So when Jim and I got married, there were only a handful of states where it was legal. So yeah, he’s right. I think it had the most impact. It was an international event.

Do you have any regrets, looking back at your career of LGBTQ advocacy?

I am regretful that we had the problem with regard to including transgender people [in the Employment Non-Discrimination Act in 2007]. There was a misperception that Nancy Pelosi and I were somehow failing the transgender community. We were in fact working very hard to get them included. And the question then was, do you take a major step forward if you can’t take [it completely]? And I think that is a shame. I think we did the best we could.

Other than that, as I look back, I’m very proud. When I took office, there was no same-sex marriage. It was illegal for people to have sex with someone of the same sex. You could not be an [openly gay] immigrant to America. You couldn’t serve in the military. I was a participant in Congress on getting rid of laws on the books that discriminated against gay people.

What do you make of the current status of trans rights?

It’s behind, because we are behind in the progress of educating the public. From the beginning of what was called [the gay rights movement], until well into the ‘90s, there wasn’t much [mainstream] conversation about trans people. I think the key to defeating prejudice is reality. More gay and lesbian people initially came out than did transgender people. [Trans people] had fewer options. I think we are now, in regards to transgender people, where we were with regard to gay and lesbian people maybe 20 years ago.

Read more: Biden Vowed to Protect the LGBTQ Community. But What’s Really Changed for Transgender People?

So I would say the current state of transgender rights in much of the country is still not where it should be. And the reason in part is that we got started later. But we’re making progress.

Going back to the ‘80s, the Washington Times reported in 1989 that you’d had a relationship with Steve Gobie, a male prostitute. A House Ethics Committee investigation found that you’d used your Congressional office to fix 33 of Gobie’s parking tickets and misstated facts in a memo to Gobie’s probation officers. The House of Representatives ultimately voted to reprimand you. Do you think that “scandal” would be treated the same way if it happened today?

I don’t know. I would say a couple of things. First of all, in an odd way that helped me explain to people why I’d come out. Remember, several of my liberal colleagues had said, ‘Oh, why are you coming out. You don’t have to do that.’ And when the Gobie thing broke, I said, ‘Now you understand why I came out.’ Because as long as I was closeted, I found it impossible to have good, healthy relationships.

The key elements were there was no coercion, no abuse of authority, no serious element of misuse of public resources. If any of those [issues] had been present, the answer would definitely be yes. Absent them I don’t know.

Some on the left have expressed concern that the 6-3 conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court could erode LGBTQ rights in the name of religious liberty. Are you concerned at all about this?

Yes I am. They’re not going to undo marriage. But I do worry about entities that get public tax money to perform services—they should not in my judgment be allowed to exclude people because of some religious disapproval of their sexual practices. It’s the sword versus the shield. The shield, in legal terms, is a doctrine that prevents other people from intruding on you. A sword is used to intrude on others. And while religious liberty should be a shield, there are concerns that people might make it a sword.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Madeleine Carlisle at madeleine.carlisle@time.com