In 2016, my doctor, Kelly Baek, a no-nonsense reproductive endocrinologist in L.A., gave it to me straight: “Your best chance for a healthy baby would be surrogacy.”

I had been through an adenomyosis diagnosis and more miscarriages than I could confidently count, and all I could do was nod. I was not ready to do that. I wanted the experience of being pregnant. To watch my body expand and shift to accommodate this miracle inside me. I also wanted the experience of being publicly pregnant. I would shake off the distrust society has for women who, for whatever reason—by choice or by nature—do not have babies. I had paid the cost of that for years, and I wanted something for it.

I held out for a year after Dr. Baek suggested surrogacy, and instead chose to endure more IVF cycles and losses. Everyone comes to the decision differently. Near the end of that year—that hopeful and hopeless year—I had a new plan to take Lupron, which basically quiets the adenomyosis. Dr. Baek told me I would have a 30% chance of bringing a baby to term. But the side effects of Lupron can be intense: you’re basically throwing your body into early menopause and you can break bones very easily.

It was something my husband said that changed my mind. I told him I wanted to try the drug. Dwayne was quiet, then said, “You’ve done enough.”

Read More: Why We Shouldn’t Be Afraid to Talk About Our Miscarriages

There was a desperation dripping off him that I couldn’t ignore. A desperation of wanting things to be right with us.

More from TIME

In 2013, before we were married, Dwyane had a baby with another woman. It should go without saying that we were not in a good place at the time that child was conceived. But we were doing much better when he finally told me about the pregnancy. To say I was devastated is to pick a word on a low shelf for convenience. There are people—strangers I will never meet—who have been upset that I have not previously talked about that trauma. I have not had words, and even after untold amounts of therapy I am not sure I have them now.

“You’ve done enough,” he said.

I looked at D with an instantaneous white-hot rage. I was fighting with my husband about what was best for my body? Did he really think that surrogacy and a baby was our chance to set it right? To rebalance? I said coolly, “You’re going to be the voice of reason now? Really?”

He looked me in the eye. “As much as we want this baby, I want you,” he said slowly. “We’ve lost too much in our relationship for me to be okay with encouraging you to do one more thing to your body and your soul.”

I read those words now and hear them again. I didn’t receive this as concern at the time. It sounded like an acknowledgment of failure. Because at that point I would have sold my soul to get out of the endless cycle of loss. What was the going rate for souls? What was mine worth, anyway? The experience of Dwyane having a baby so easily—while I was unable to—left my soul not just broken into pieces, but shattered into fine dust scattering in the wind. We gathered what we could to slowly remake me into something new. There was no way to disguise where I’d been glued back together.

Clearly, my feelings weren’t originating from a healthy place. So much of what made the decision so difficult was that if I didn’t submit to a surrogacy, then I was convinced I needed to let Dwyane go. Even if he didn’t want to, I had to let him find someone who could give him what he wanted.

But I loved him. Each day, he had worked to be forgiven, and I had chosen to do so. And part of this journey of making peace with our love is also making peace with ourselves. I had come to accept that without that awful collision in our lives—this Big Bang moment in our relationship that set our galaxy as we knew it—we wouldn’t have become the individuals we wanted to be. The me of today would not have stayed with him, but would I be who I am now without that pain? I remember a small voice in my heart telling myself to leave, but my fear of public humiliation was so great that I didn’t take my own advice.

In the aftermath, I invested so much time in making peace between us that I gave myself absolutely no self-care. And now there I was, still putting my life second to some shared mission. Why was I so willing to risk myself for a chance? If there was another way for me to bring my baby into the world, and have my health, why was it so hard for me to make peace with that?

For weeks, I went down a rabbit hole of books, surrogacy message boards and conversations with our fertility agency. At the top of the surrogate food chain were married, white, American women who have their own kids. The belief is that if they are married, they have a built-in support system, and if they have more than one child, there’s proof they can do the job. On the message boards, people can be anonymous, so they rank surrogates by race. I got the sense a lot of white families-to-be were more comfortable with brown people as surrogates—Latina and South Asian—who were often classified as “breeders.” Now, I am Black, and I am used to hearing how people speak of women of color, but this was some Handmaid’s Tale sh-t.

We chose the most ethical agency we could find, and answered most of their questions about prerequisites with “We don’t care.” Religion, active lifestyle, diet. Two months later, in early December, we were presented with a surrogate who seemed to check all the boxes. We were introduced over the phone, but the conversation was made awkward by the fact that we couldn’t reveal our identities to protect the anonymity of both parties. She said all the right things about how she experienced the gift of life having her own kids, and wanted to give this gift to others. But I was cautious, wondering if people were prepped to say that.

After she was cleared by Dr. Baek, we agreed to meet in person in her office. As I got dressed that morning, I realized this was like the best and worst blind date ever. I wondered what outfit said, “I’m grateful, but I’m also not a loser. And I’m not some actress, you know, farming out her responsibilities.” This woman and her husband had the power to look at me and say, “Ennh . . .” I needed her to like me and accept me. Accept us, since I was also standing in for Dwyane, who was in the middle of the season. I was very aware that the surrogate and her husband didn’t know we were Black.

I got there early. Dr. Baek put me in a small office, and the liaison from our agency arrived. “Are you comfortable?” she asked. I smiled and nodded, unable to put words to the feelings. There had been so much fear and failure, but now there was a vague relief that I was finally here. And something else: anticipation. I had not let myself have that for so long that I had difficulty recognizing it.

The door opened. Like a blind date, you look everywhere at once, knowing you are being looked at, too. The first thing I noticed was a nose ring. Oh, I thought, she’s a cool-ass white girl.

And then I noticed her notice me. Her eyebrows shot up. “Oh, ho ho ho,” she said. There was an excitement to her voice, and I smiled. “This is such a trip. I have your book on hold at four different libraries.”

I have never been done wrong by readers. I started laughing, and we hugged. “So, I guess now I can get a copy, huh?” she joked.

“Yeah,” I said, meaning yes to everything. Her name was Natalie, and when her husband came in I saw they matched. Free spirits with an aura of goodness to them. They had an easy rapport and were affectionate with each other. I hadn’t known that would be so important to me, knowing that she had a partner in this. I called D and put him on speaker, and as they directed their attention to the phone, I looked up at them. You’re those people, I thought. You really want to help others.

When we got the positive pregnancy test in March 2018, my first thought was, “Wow. Sh-t. This is really happening.” The due date was Thanksgiving.

We’d even begun to pick out names. When I was in my 20s and thought my life was going to be a little different, I’d begun keeping lists of baby names. There was one name I saw at the end credits of a TV show or movie: Tavia. That would be pretty, I thought, with a K. Kavia. That name made it onto every hopeful list I kept. Dwyane knew the list by heart, too, and we both felt it. This hope, this starburst, was her.

Near the end of the first trimester, we all returned to Dr. Baek’s office, this time with Dwyane, for the first 4-D ultrasound. Two couples crowded into a room built for one, awkward in our affection for each other, yet still feeling like strangers. This was the first time Dwyane had met Natalie and her husband in person, and our hugs were those of people who did not know each other but had survived something as a unit. She was showing me her stomach, turning to the side, cupping the weight of my own maternal ineptitude. This growing bump that everyone thought I wanted to see was now a visual manifestation of my failure. I smiled, wanting to show I—we—were so happy and grateful. But part of me felt more worthless.

Natalie lay down for Dr. Baek to pass the ultrasound wand over the bump. “There she is,” she said. And she was. There. Here. This very clear little baby in there. Her big-ass head, her spine, her little heart pumping, pumping, pumping. Determined to live. It was suddenly incredibly real. Dwyane took my hand, and there was so much happiness on his face, I lost it. My cry was a choke stopped up in my throat, tears streaming down.

It was grief. I’d had so many miscarriages. I say the following with the caveat that I am steadfast in being pro-choice. I was on a fertility journey at 44. The smallest cell was weighted with the expectation of life. A zygote was a baby, just on potential alone. When one of my eggs was examined, that was a baby. When Dwyane got a sperm analysis, that was a baby. Every swimmer was our baby. But when I miscarried in the first trimester, I never thought I had lost a baby baby. I had never let it count. Looking at the screen, I understood how many potential babies I had lost. That’s why I was crying. A floodgate of grief and sorrow overcame me, threatened to drown me.

I saw my husband so happy, and I was not a part of it. I felt a chasm widening between us. I was embarrassed to be crying so much, but everyone was looking at me with smiles and nods. They thought these were tears of gratitude. The awe of witnessing the start of life. I was reliving death. Of course I was grateful, it would be impossible not to be. But what I was grateful for was that this life might be spared. That this heartbeat might continue, beat strong for decades, long after my own stopped. So many had stopped inside me.

I allowed the misreading of my tears. Crying showed that I was a good mom. My first performance in competitive mothering. Nailed it.

I was on the other side of the world from my daughter when I began to let myself look forward to her arrival. We were in Beijing on business for Dwyane and brought friends with us. It was the end of July, the five-month mark we had never made it to. Dwyane’s confidence was something to behold and envy. He was so certain she was going to make it that we told our friends. After my first miscarriage, I had never ever told people when we were expecting. Even this felt dangerous. The words were out of my mouth to my friends and I thought, What the f–k did I just do?

Dwyane broke out whiskey and cigars, and he announced that he wanted to get a tattoo of her name—we’d decided it would be Kaavia James—on his shoulders that night, written where his Heat jersey would cover it. I was terrified of the permanency. As he sat before me with his shirt off, I placed my hands where her name would be, and kissed the top of his head. I thought of something he would sometimes say to himself and to others: “My belief is stronger than your doubt.” He usually said this when he was counted out after an injury, or walking away from a deal everyone thought he was crazy to turn away. But this was different. I didn’t know if his belief was strong enough for both of us.

Then, a week after my late-October birthday, I was on my way to the gym before work. It was 11 a.m., and I’d been on the set late the night before. My phone rang. I looked down and saw Natalie’s name.

“My water broke,” she said.

“Hunh?”

I had Kaavia James’s due date in my mind as set. She would be here at Thanksgiving. I was just getting used to it being November.

“I’m headed to the hospital now,” she said. “Okay!” I said. “Okay.”

I called D. He was in Miami, and in the first few weeks of his final NBA season. He’d had a plane on standby for just this moment, and called the pilot right away. I called my mom in Arizona, and she got on the first flight. What happened next—more phone calls, a trip home for my pre-packed bag, booking a hotel room near the hospital—happened fast. My mom got there before Dwyane. D arrived, followed by the baby nurse and her crew.

And then Natalie proceeded to go into labor for 38 hours—so long that Kaavia James was in danger. The doctor had to do an emergency C-section because the umbilical cord had become tied around Kaav’s ankle. Now that I am Kaavia James’s mother, I know that she tied it herself because she was simply over it.

I definitely didn’t know how C-sections work. Turns out it’s all kinds of rough. But it was fast, and suddenly the doctor was holding her up for our wide-eyed gaze.

“Oh my God,” I said. The room was festive almost, people saying over and over, “Congratulations.” Just as quick, the doctor placed her on a little exam table and asked her name.

“Kaavia,” I said, my voice a choke.

This baby, given a name written on a wish list for decades, then tattooed on her father’s shoulders. She was loved even as an idea. My body seized in a full release of every emotion. Relief, anxiety, terror, joy, resentment, disbelief, gratitude . . . and also, disconnection. I had hoped that the second I saw her, there would be a moment of locking in. I looked over at Natalie and her husband. There was a stillness to them. I looked at Kaavia James on the table, and then back at them. It took all of us to create her, so I wanted to share this time with them.

The nurses took Kaav to the newborn nursery. Dwyane, my mom and I all reassembled in a hospital room, waiting for them to weigh Kaav and clean her up. I put on a surgical gown for modesty so I could do skin-to-skin bonding with her. My mother and D were crying, our surrogate was crying, our baby nurses were crying, and I was a mess. Then the door opened and Kaavia James was brought into our lives.

So much time has passed. So many firsts. Yet the question lingers in my mind: I will always wonder if Kaav would love me more if I had carried her. Would our bond be even tighter? I will never know what it would have been like to carry this rockstar inside me. When they say having a child is like having your heart outside your body, that’s all I know. We met as strangers, the sound of my voice and my heartbeat foreign to her. It’s a pain that has dimmed but remains present in my fears that I was not, and never will be, enough.

And Dwyane leaves me with another riddle that has no answer. I can never know if my failure to carry a child put a ceiling on the love my husband has for me. Yes, I am Baby Mama number three, a label that is supposed to be an insult. But is the injury not that label but instead the asterisk next to my name in the record? The asterisk denotes that the achievement is in question. “She didn’t really earn the title.”

If I am telling the fullness of our stories, of our three lives together, I must tell the truths I live with. And I have learned that you can be honest and loving at the same time.

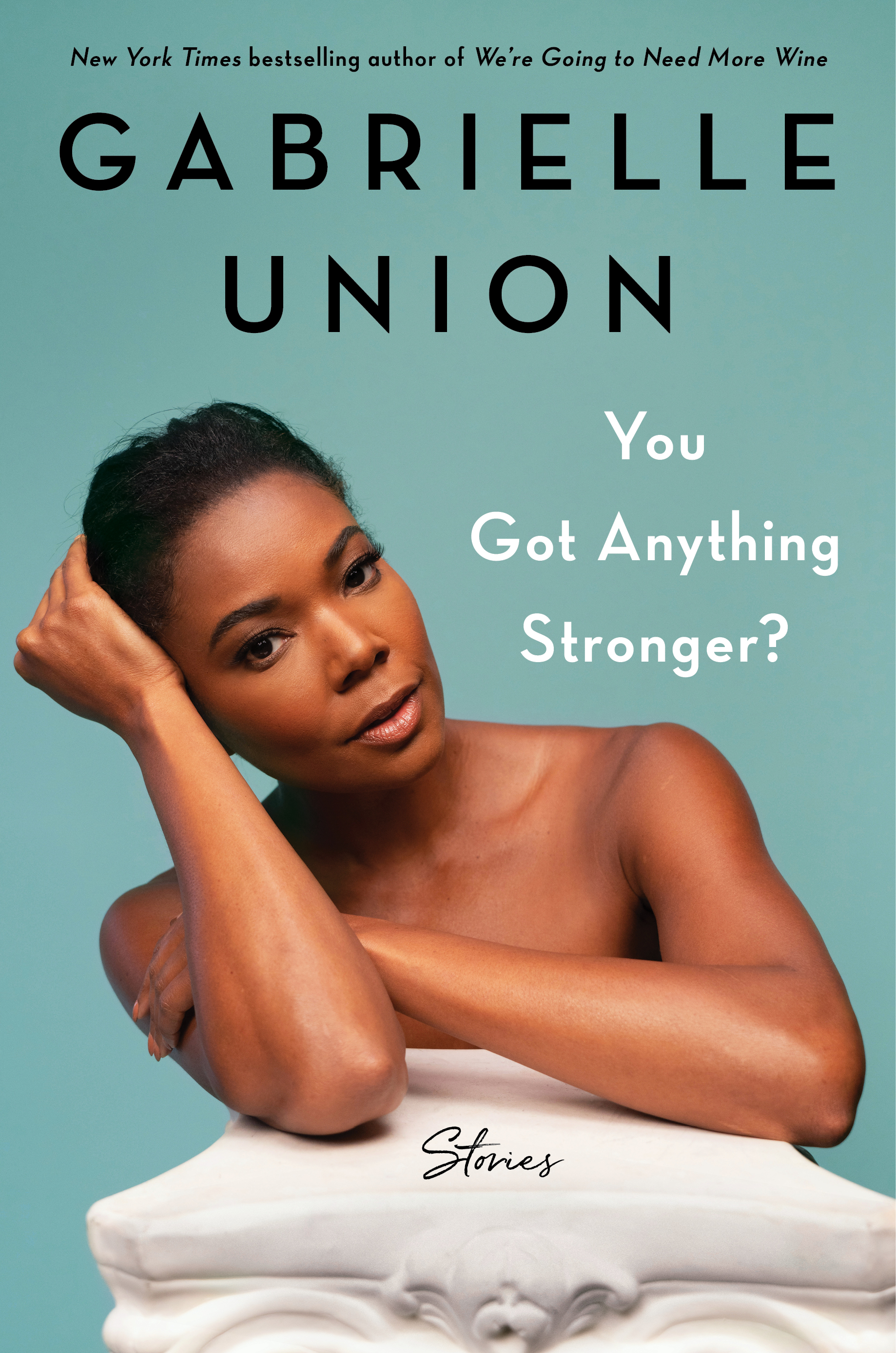

Adapted from You Got Anything Stronger? by Gabrielle Union. Copyright © 2021 by Gabrielle Union. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com