The crackle of handheld radios broke the morning stillness. Sound carries in the country, and on the rural outskirts of Arab, Ala., curious neighbors stepped onto their porches, craning their necks to see what was going on. Some thought the police had found an escaped inmate who had been a leading story on the local news. But even from afar, there was no mistaking the outsize yellow letters on the uniformed figures entering the single-story house at the end of the two-lane road: FBI.

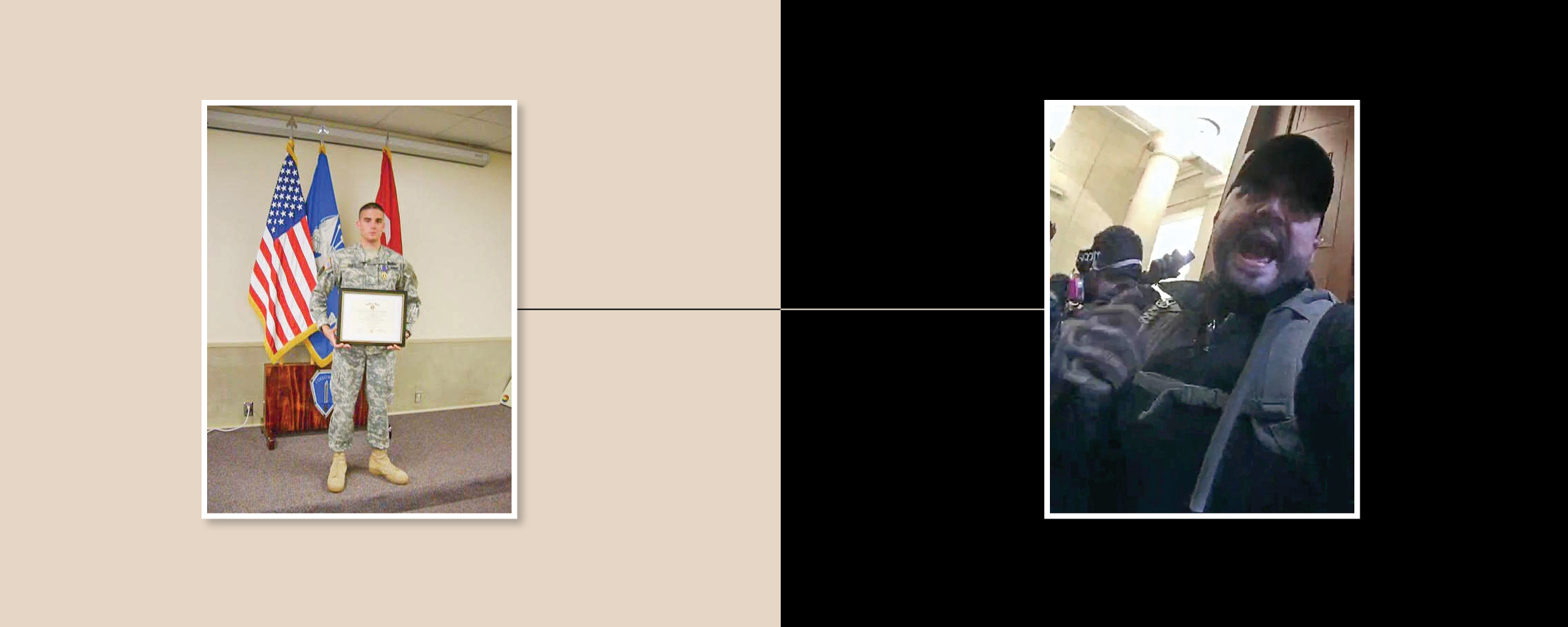

The word spread quickly. Claudia Schultz was walking out of her jewelry shop on the town’s small main street when another store owner told her Joshua James had been arrested. Schultz was incredulous. “Josh? You mean our Josh?” In Arab, a town of 8,380 in northeastern Alabama, much of the community knew James, 34, as a soft-spoken, God-fearing family man with three young kids who ran his own pressure-washing business. Those who knew him better considered him a local hero—an Army combat veteran and Purple Heart recipient who got choked up when he talked to local teenagers about enlisting in the U.S. military.

But the federal agents who showed up on James’ doorstep on March 9 described a very different man: an extremist who had not just broken the law but also carried out an assault on the same government he had sworn to defend as a soldier.

For weeks, James had helped plan an operation to disrupt the certification on Jan. 6 of President Joe Biden’s electoral victory, investigators say, by coordinating and recruiting others to travel to Washington with paramilitary gear, including guns, tactical vests, helmets and radio equipment. A federal conspiracy indictment contends James and at least 15 other members of the Oath Keepers, an anti-government militia, had organized, equipped and trained ahead of the siege that left five dead and dozens more injured. James was among the throngs of supporters of defeated President Donald Trump who rammed their way into the seat of American democracy. “Get out of my Capitol,” James allegedly shouted at riot officers. “This is my f-cking building!”

For many, reconciling the war hero and family man with the Jan. 6 insurrectionist is not easy. Federal prosecutors have described the Capitol rioters as a fringe group of violent extremists, conspiracy theorists and madmen. The man presiding over James’ case professed bafflement. “Mr. James, I’ve got to tell you, I’m not sure of why anyone in your position, given the life that you’ve led, would do this,” D.C. District Judge Amit Mehta told him at an April hearing.

If James’ decision to leave his family to join an attack on the U.S. Capitol is a mystery, there are clues to what drove him. After his service, and rehabilitation from his injuries, he struggled to rebuild his life. In that, he was not alone. Of the more than 500 people arrested in connection with the Jan. 6 riot, at least 1 in 10 was a current or former member of the U.S. military, according to a George Washington University analysis. Many had served in the protracted post-9/11 conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, returning home to a country that paid them lip service but moved on without much notice to the wars they had fought.

Over time, James found community in the Oath Keepers, which used the familiar terminology and camaraderie of military life to mobilize vets in support of a variety of right-wing causes. In doing so, prosecutors allege, its members miscast criminality as patriotism. The communications between James and other veterans on Jan. 6 were full of phrases like save the Republic and defend America, according to court filings. Many claimed they had been betrayed by U.S. politicians who were the true enemies of the state. The insurrectionists’ grievances were so strong, prosecutors allege, that they took the law into their own hands.

But this view has found strong support across the country. In Arab, where American and Confederate flags compete for space on some front porches with make America great again banners, more than two dozen residents described the events of Jan. 6 to TIME as a legitimate protest over an election they wrongly believed to have been fraudulent. Yes, it got out of hand, they say. But many saw James as a man motivated by love of country, exercising First Amendment rights, who was ensnared in a politicized witch hunt. “I quite frankly believe him to be an American hero,” says Rachel Ann Halligan, who lives close to the Jameses in Arab. “The corruption and fraud that is being perpetrated by our government is absurd.”

This account is based on interviews with more than two dozen friends, neighbors and community members in Arab; people who knew James through his military service and business dealings; his archived social media posts; and a review of FBI and federal prosecutors’ legal filings.

James’ guilt or innocence will be determined at trial. Federal prosecutors will present evidence that he violated multiple laws in an insurrection against the country he had sworn to defend.

But the forces that fed James’ alleged insurrection may be too deep-rooted to be resolved by the trials. In many communities like Arab, the radical path James took on Jan. 6 seems patriotic rather than criminal; for some, the law itself seems almost a sideshow. “Everyone has the right to stand up for what they believe,” says Ramsay Vandergriff, a 38-year-old electrician. “It could easily have been me. It could easily be any of us.”

“I’m a normal dude,” James tells the camera in a video posted to his wife Audrey’s TikTok account in early June. He plants kisses on her cheek and turns back to the grill as she films them in their yard. “Just a normal man,” she repeats, punctuating her words with exasperated sighs. “A Purple Heart recipient, veteran, grilling dinner for his family.” Audrey tells her new followers that she can’t reveal much more; since posting about James’ arrest and her family’s ordeal, she has gained a sympathetic audience of more than 18,000 on the social app. But the video pans out to show the ankle monitor that has tracked James’ movements since April. “The FBI is kind of crazy,” she says. “It’s unreal every single day.” (Both James and his wife declined interviews for this story, citing ongoing court proceedings.) He has pleaded not guilty.

The man in these posts comes across as a devoted dad and husband with a wry sense of humor, who likes fishing, grilling and secretly watching The Golden Girls. He occasionally jumps into Instagram videos advertising Audrey’s real estate business. The oldest of six siblings, James grew up in San Jose, Calif., playing football and the guitar. As he approached the end of high school four years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, he decided to follow in his uncle’s footsteps and enlist in the Army, motivated by the idea of serving his country while also setting up a stable life for himself. Before he deployed to Iraq in March 2007, at the height of the U.S. military surge, he got a tattoo on his right forearm: death before dishonor.

On June 7, the 19-year-old Army private was in the turret of his armored truck outside Baghdad. His eight-man unit had spent hour after eye-glazing hour staring at the arid terrain, hunting for signs of buried roadside bombs. Suddenly the road erupted into a fireball. “A dump truck full of 2,000 lb. of homemade explosives blew the bridge in half that my squad was on,” Sergeant David Aleman, the unit’s squad leader, tells TIME.

The blast killed three and wounded several others, including Aleman. It rocked James’ head and neck, shattering his jaw as the column of a nearby building collapsed on him. Smoke and blood filled James’ nostrils. Scrambling in the chaos, someone in the unit managed to radio for medical support. “It is a miracle,” Aleman says, “that some of us survived.”

For James, the months that followed were a blur of surgeries and physical-therapy sessions, first in Europe and then in Fort Bragg, N.C., before he settled in Florida. His body slowly healed, but he was forced to take medical retirement from the Army, and struggled to adapt to postmilitary life. He suffered from PTSD, anxiety and depression as his personal relationships came under strain, according to legal filings. In 2011, James was charged with prowling when he was found handing out flyers for a moving company in a gated parking lot in Jacksonville. He faced a felony charge of impersonating a law-enforcement officer after police said he falsely claimed he was a member of the military police. The charges were ultimately dropped.

Things finally started falling into place on the night in 2014 when he took Audrey on a first date to a comedy club. She later posted on Facebook that she laughed so loud, she embarrassed him. The two had met years earlier, when Audrey was still married to another soldier and James’ jaw was still wired shut. She would later joke to friends that she liked it better that way. They married in 2016.

All the while, James’ prior military service remained an important part of his life. He became involved with local chapters of the Oath Keepers in central Florida, whose recruiting materials reminded members that their oath was forever. “America’s veterans truly are like a sleeping giant. It is time to awaken them and fill them with a terrible resolve to defeat the domestic enemies of our Constitution,” says one chapter’s mission statement, according to documents reviewed by TIME. “If we can’t get the veterans to step up … to save our Republic, then how can we expect to get the rest of our people to do what must be done?”

In September 2017, James traveled to the Florida Keys with members of the group to help disaster-relief efforts after Hurricane Irma devastated the area. He volunteered to drive one of the trucks, delivering pallets of rice and beans. “As Oath Keepers, we are on location helping … by any means necessary,” he wrote in a now deleted Instagram post with the hashtags #patriots, #selfless and #forthepeople. Videos posted to YouTube at the time show him standing next to the local chapter’s self-professed leader, Kelly Meggs, passing out water bottles to locals.

In 2018, Joshua and Audrey moved their newborn son and Audrey’s two children from her previous marriage to her hometown of Arab to be closer to her family. There, he received treatment through Veterans Affairs and launched American Pro Hydro Services, a pressure-washing business that advertises with patriotic red, white and blue logos that it is “veteran-owned.”

James also seemed to stay in touch with members of the Oath Keepers back in Florida and make connections with new ones in the region. On social media, his wife referred to James’ network of “fellow vets/retired police,” seemingly in reference to the Oath Keepers. But with no active chapters near him, James seemed to drift toward right-wing spaces online. His YouTube habits mixed fishing and cooking accounts with a range of far-right conspiracy and survivalist channels. On Pinterest, he saved images of American flags and eagles with quotes like “I have the right to bear arms: your approval is not required.” His page included posts linked to sites like Patriot Depot, which advertises “supplies for the conservative revolution,” alongside styling ideas for his daughter’s hair.

By 2020, even the professional social media presence of the pressure-washing business James had painstakingly built had started to slip. “Invoke the Insurrection ACT NOW!!!” the handle for American Pro Hydro tweeted at Trump in August 2020 in response to the President’s tweets about racial-justice protests. The following month, James joined Parler, a largely right-wing social media site, where he followed a slate of conservative figures, accounts like the conspiracy website Infowars and fellow Oath Keepers. “Looking forward to meeting everyone!” he posted on Sept. 8.

After the election, James began traveling with the Oath Keepers to events in Texas, Georgia and D.C. to provide “security” for right-wing speakers, including longtime Trump adviser Roger Stone, retired general Michael Flynn and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. These trips were frequent enough that his wife received $1,500 in several payments from January to March from an Oath Keepers account through a mobile cash app “to help support my children while he was not there,” according to her March 11 deposition.

On Nov. 21, James attended a “Stop the Steal” rally in Atlanta, where speakers urged participants to “accept nothing less than a Donald Trump victory.” A photo from the event shows him wearing a bullet-proof vest with the Oath Keepers logo and the motto “Guardians of the Republic/Not on Our Watch.” Although James deleted most of his social media, an archived version of his Parler account shows his posts were peppered with hashtags like #stopthesteal2020, #saveamerica and #deepstatecorruption. He posted a photo from a “Stop the Steal” rally in front of the White House on Nov. 14 with the caption “Communists and CCP Loyalists want to change our way of life!”

It was a dramatic evolution for a man who hadn’t been registered to vote before 2015 and only joined the NRA the following year. Friends and neighbors never thought of James as particularly political beyond holding the standard conservative views that are common in Arab, which is in the nation’s most conservative congressional district. As with other veterans whose involvement in right-wing groups like the Oath Keepers led them to the Capitol on Jan. 6, James’ descent into alleged extremism seemed less an expression of long-held political fervor than the desire to be part of a larger patriotic cause.

Little data is kept on how often and why veterans get involved with extremist groups, but there are plenty of high-profile examples throughout American history. Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate army general, was the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. George Lincoln Rockwell, a Navy veteran, founded the American Nazi Party. Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, both Army veterans, were convicted of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing.

Founded by a former Army paratrooper in 2009, the Oath Keepers has quickly become one of America’s largest antigovernment extremist groups. It heavily recruits current and former military and law-enforcement members, encouraging them to see themselves as “the last line of defense against tyranny,” according to Oath Keepers websites. The group’s name refers to the oath sworn by members of the military and law enforcement “to defend the Constitution from all enemies, foreign and domestic.” Some members falsely believe that the federal government has been taken over by “a cabal of elites actively trying to strip American citizens of their rights,” according to the FBI.

Groups like the Oath Keepers exploit the sense of isolation that plagues many returning combat veterans. Most U.S. service members have no ties to extremist organizations, but the government has long warned about such groups’ desire to enlist returning veterans into their ranks to exploit their tactical skills and combat experience. A 2009 Department of Homeland Security assessment said right-wing extremists “will attempt to recruit and radicalize returning veterans in order to boost their violent capabilities.” This disaffection is often particularly acute for soldiers of James’ generation, who served in America’s longest wars as the country gradually became more detached from overseas conflicts, says Kathleen Belew, author of Bring the War Home: The White Power Movement and Paramilitary America. The Oath Keepers peddles an opportunity to continue their service. “Militia groups have really familiar structures of command,” Belew says. “They have structures of fraternal bonding, they have the organizational social elements that are very similar to the armed forces—and they’re built that way deliberately.”

Prosecutors say James’ main contact at the Capitol was Kelly Meggs, with whom he had distributed disaster-relief aid in 2017. According to federal investigators, the Florida militia leader not only organized the Oath Keepers but also planned to join forces with other extremist groups, including the Proud Boys and Three Percenters, on Jan. 6.

Court filings in James’ case portray him as a key figure in the plan to storm the Capitol. Chats with other Oath Keepers on the encrypted messaging app Signal “demonstrate that the defendant was designated as a leader in the group, and that he operated as one early on,” according to prosecutors. James allegedly fielded messages from other men in Alabama eager to join his “quick reaction force” (QRF) team. When one said he had friends near D.C. willing to help with “a lot of weapons and ammo if you get in trouble,” James responded, according to prosecutors. “That might be helpful, but we have a sh-tload of QRF on standby with an arsenal.” On Parler, James chatted with Roberto Minuta, a New York tattoo artist and member of the Oath Keepers. “I’ve been hoarding any ammo I can get my hands on lol,” Minuta responded in December to a photo James had posted of his guns and ammunition.

At around 2:30 p.m. on Jan. 6, James and Minuta were allegedly spotted on security cameras speeding toward the Capitol in two golf carts as James shouted directions from the map on his phone. While they made their way, a group of seven Oath Keepers were preparing to climb the Capitol’s east stairs in a tactical formation, according to the federal indictment. To pierce the mass of people gathered there, each group member placed a hand on the back of the person ahead—a military-style tactic prosecutors called a “stack.” The group forcibly entered through the Capitol doors, where James and Minuta followed 25 minutes later. “Patriots storming the Capitol building,” said Minuta, according to prosecutors. “F-cking war in the streets right now.”

Investigators say James exchanged at least 10 calls and texts that day with fellow militia members, nearly all of whom were clad in tactical vests, helmets and other gear, while terrified lawmakers inside the building hid and ran for their lives. In the process, prosecutors allege, James had broken multiple laws barring conspiracy, obstruction and entering a restricted building.

In Arab, the chaos in Washington felt far away. A town that was named after a typo, it was meant to honor the founder’s son, Arad Thompson, but the U.S. Postal Service misspelled the name in 1882 and the mistake stuck. The community decided to lean into the moniker, referring to their football team as the Arabian Knights. Arab is 98% white, with more than three dozen evangelical churches and what locals fondly refer to as “strong traditional values.” Stores in town sell “Rulers of the South” memorabilia featuring Confederate generals. It holds an annual Back-When Day to demonstrate 1800s “quilting, cornmeal-grinding, and black-smithing.”

When James quietly returned to Arab from the capital, he resumed his life as normal. He pressure-washed driveways, posed for selfies on Valentine’s Day, donned a tie for Audrey’s real estate banquet and collected disaster-relief supplies with fellow veterans after a deadly tornado in Fultondale, Ala.

But privately, James seemed to grasp the gravity of the situation. Two days after the insurrection, he encouraged other Oath Keepers to delete and destroy their communications on Signal, texting them to “make sure that all signal comms about the op has been deleted and burned,” according to federal investigators.

Sixty-two days later, a new customer rang James’ phone in need of a pressure-washing job. It was a ruse. While he was away, FBI agents, with the local sheriff and police in tow, rumbled up to his front door in a vehicle neighbors described as a tank. After asking James’ wife and 3-year-old son to step out of the house, they demanded to know if he was building a bomb. Then they flew a drone inside to make sure. For eight hours, they searched the family’s 1,300-sq.-ft. home, rummaging through closets, cabinets and garage boxes. James was arrested and charged with crimes carrying a maximum penalty of 20 years in prison.

In a courtroom in Birmingham two days later, his lawyer argued that James was being treated unfairly. “He didn’t kill anybody. He wasn’t acting violently. He is a person who has followed orders all his life, your honor. An individual who would risk his life for strangers.” The judge disagreed. “You were involved in planning some of this operation,” he told James. “There’s no remorse there, and there’s no recognition of the lasting damage that was done on Jan. 6.”

The judge ordered James to be kept in jail because of his past record of PTSD, anxiety and depression, as well as a previous hospitalization. James’ lawyers objected; to them, it seemed the judge felt he posed a danger to the community because he had suffered unseen wounds during his combat service. Many of those previously arrested for their alleged roles in the Capitol riot, the lawyers noted, had already been set free.

The news shook the town. At first, Audrey tried to defend her husband online. “He wasn’t in the riot,” she posted in the Facebook comments section of Arab’s small newspaper. “He’s not the man the media is making him out to be.”

Many in the community offered an outpouring of assistance. Complete strangers knocked on the door of the James’ home to drop off small amounts of cash and tell them “we’re praying for you.” The family also received an outpouring from outside Arab. More than $184,000 in donations flowed in through an online fundraiser for which Audrey provides regular updates. The funds allowed them to hire Washington lawyers, Joni Robin and Chris Leibig, who say James intends to fight the charges. “There are two sides to this story, and so far the only version of events you’ve heard is the government’s,” Robin says.

Those in Arab who don’t support James have mainly stayed quiet. “Little towns ain’t no joke,” one person who lives near James tells TIME. “I’d really rather my house not get burned down, ya feel me?” Another neighbor who spoke to local media the day of James’ arrest was attacked on social media as a “rat-faced snitch.”

That hasn’t stopped everyone from speaking out. “I wish he had stayed home with his family,” wrote one Arab resident on the local paper’s Facebook page. “He should have thought about them when he decided to be a domestic terrorist,” another community member retorted.

To Patrick Tays, a 73-year-old disabled Navy veteran who lives in Arab, James and his allies are “traitorous scumbags.” “Washington would have hung them,” he says. “Lincoln would have shot them. Teddy Roosevelt would have them all in prison.”

Only now are federal authorities formally drawing up a strategy to handle the problem of military veterans’ joining extremist groups. The Biden Administration’s strategy to combat domestic terrorism includes plans to prevent veterans from being recruited by extremists. Currently, there are no efforts that focus on veterans once they have left service, despite evidence that they are increasingly the targets of online misinformation and extremist recruitment.

Security analysts, veterans’ groups and experts say it will be vital to combat both the isolation and the fear-mongering that lead former service members to think of their fellow Americans as the enemy or, worse, take the law into their own hands. “It’s important not to fixate too much on the Oath Keepers as an organization but to think of them as a concrete example of a broader phenomenon in America,” says Sam Jackson, a homeland-security expert at the University of Albany who wrote a book on the group. The alleged radicalization of James, the growth of local chapters and the national organization should be “seen as a Russian nesting doll” that shows a much larger movement, he says, “of people who view America as being hijacked by internal and external enemies.” But little is likely to change unless more Americans come to agree on what it means to be an extremist and what it means to be a patriot.

After a month in jail, James was granted bond under the condition that he get mental-health treatment, surrender his passport and agree not to communicate with other members of the Oath Keepers. The evening James returned to Arab, Schultz, the jewelry-store owner, drove to the family’s house with steaks to welcome him back. “He’s a good man,” Schultz says. “It’s just so scary. My daddy says they’re going to make an example out of him.”

James has been living under house arrest, allowed to leave only for mental-health appointments. In May, during what would be a busy season for his business, his company truck sat idle in the backyard.

At least three co-defendants in the Oath Keeper case have pleaded guilty to charges of conspiracy and obstructing Congress, and are now cooperating with the government. These witnesses’ testimony could have a major impact on James’ case.

Over the July 4 weekend, Audrey pored over their plea deals with a highlighter to understand what it might mean for her husband. Sounding incredulous, she told her TikTok followers that she was “blown away at the constitutional rights they’re signing away.” Even though his fellow Oath Keepers had pleaded guilty, she maintained James had done nothing wrong on Jan. 6. His day in court has yet to be set.

—With reporting by Simmone Shah and Chris Wilson

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Vera Bergengruen/Arab, Ala. at vera.bergengruen@time.com and W.J. Hennigan/Washington at william.hennigan@time.com