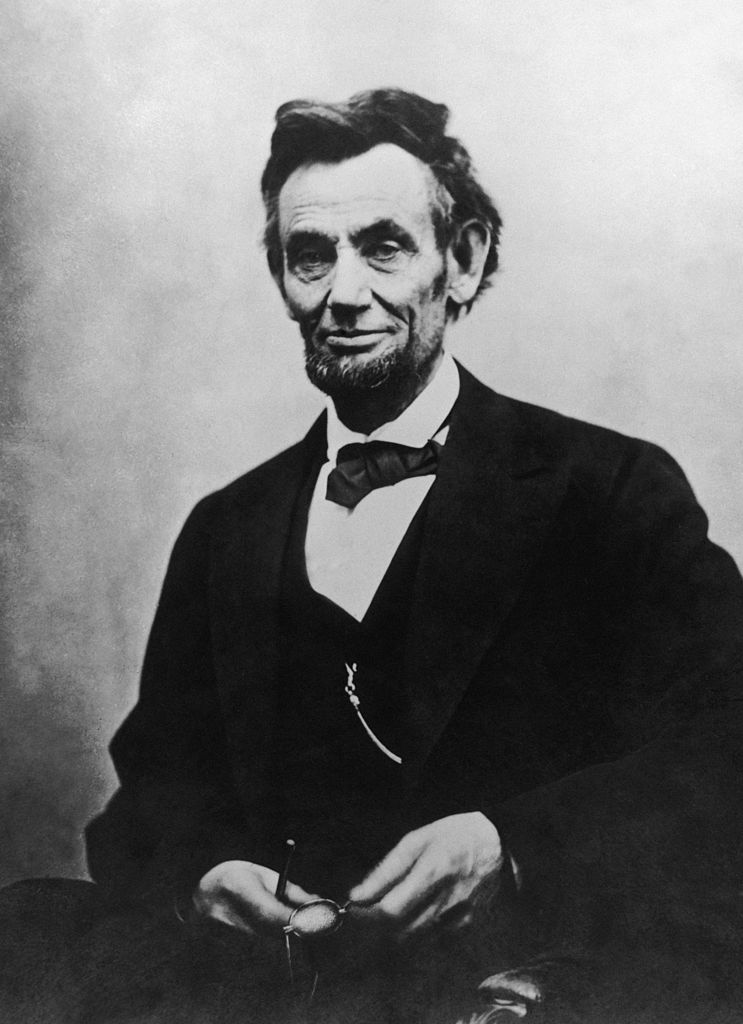

Abraham Lincoln wrote countless private notes for his eyes only—scribbled words to capture ideas and insights about the myriad problems and issues he faced. Never expecting anyone else to read them, he left them undated, untitled, unsigned. Engaging with these notes is like entering a world most history buffs do not know exists. Is there anything new they can tell us about the notoriously private president?

To read them is to look over Lincoln’s shoulder as he wrestles with the issue of slavery, thinks deeply about his dual vocations of lawyer and politician, reflects on the hurdles surrounding the birth of the Republican party, unleashes his fury on prominent pro-slavery authors, and engages in a theological rumination about the presence of God in the Civil War.

Behind their revelatory content, these fragments are a testament to Lincoln’s nimble mind. One surviving fragment is lyrical, a style not usually associated with Lincoln. Many are deductive in reasoning, using logic to ask, challenge, probe, and analyze. As an experienced lawyer, he often begins a note by advancing the logic of an opponent’s argument before articulating his own point of view on a subject. Lincoln often concludes with a resolution of the problem under investigation or suggests some future course of action.

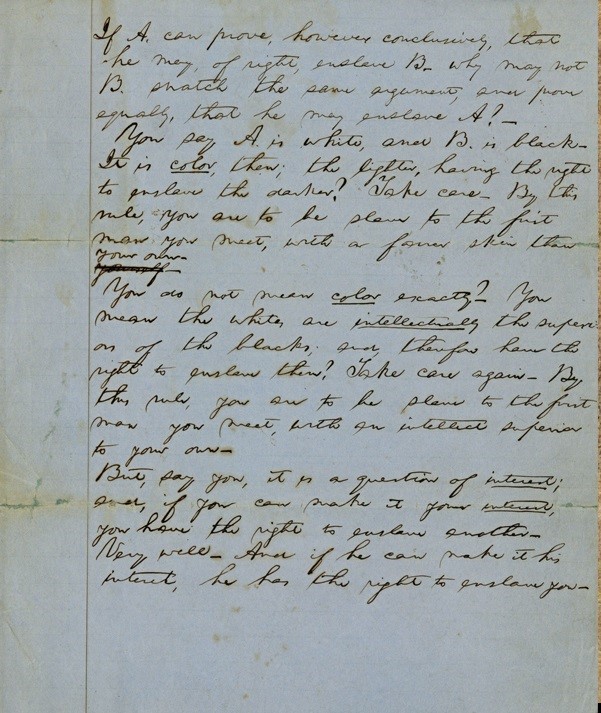

Of the 111 surviving notes, all printed for the first time in my book Lincoln in Private, some of the most fascinating focus on Lincoln’s reemergence into politics in the 1850s to battle the spread of slavery into the nation’s western territories. In this note to himself, one can imagine Lincoln pacing the floor of a courtroom as the prosecuting lawyer. Listening to his imaginary opponent: “You say;” “You mean;” then pushing back: “But say you.”

If A. can prove, however conclusively, that he may, of right, enslave B.—why may not B. snatch the same argument, and prove equally, that he may enslave A?—

You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color, then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be a slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own.

You do not mean color exactly?—You mean whites are intellectually the superiors to blacks, and therefore have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own.

But say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest, you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you.

In three successive justifications of slavery, Lincoln rolls each pro-slavery argument back on itself, showing the fundamental contradiction in each justification—be it color, intellect, or interest—that could easily be turned around to make the owner the slave.

After studying Lincoln these many years, when I immersed myself in the hidden world of his notes to himself, I found myself encountering, in many ways, an entirely new man.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com