At Time Magazine’s gala celebration of its 75th anniversary on March 3, 1998. A few guests were asked to toast someone they especially admired. John F. Kennedy Jr.—the president’s son who died a year later in a plane crash—chose, somewhat surprisingly, Robert McNamara, best known as being the defense secretary responsible for the strategy in the Vietnam war that ended with American defeat.

I was especially impressed, even moved, by the tribute because I had come to know McNamara as editor and publisher of three books, including In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam, the enormously controversial memoir about the war, released in 1995, in which McNamara wrote: “We in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations who participated in the decisions on Vietnam acted according to what we thought were the principles and traditions of this nation. We made our decisions in light of those values. Yet we were wrong, terribly wrong. We owe it to future generations to explain why.”

The furor was over why McNamara, more than two decades after the war had ended, should be, finally, acknowledging the failure. In an editorial, The New York Times said, in effect, McNamara should never be forgiven and should never have a restful night’s sleep.

This was before the advent of social media, but the uproar could have made McNamara regret his decision to write the book. He more than anyone else at the pinnacle of power in the war years had publicly recognized a major role in the debacle.

“After leaving public life,“ JFK Jr. said in his remarks. “[McNamara] kept his own counsel, though it was by far the harder choice. Years later…he took full responsibility for his decisions. Judging from the reception he got, I doubt many public servants will be brave enough to follow his example.

“So tonight, I would like to toast someone I’ve known my whole life, not as a symbol of pain, we can’t forget, but as a man. And I would like to thank him for teaching me something about bearing great responsibility with great dignity. An adversity endured only by those who accept great responsibility.”

How McNamara came to accept some responsibility for his profound mistakes is part of my new memoir, An Especially Good View: Watching History Happen.

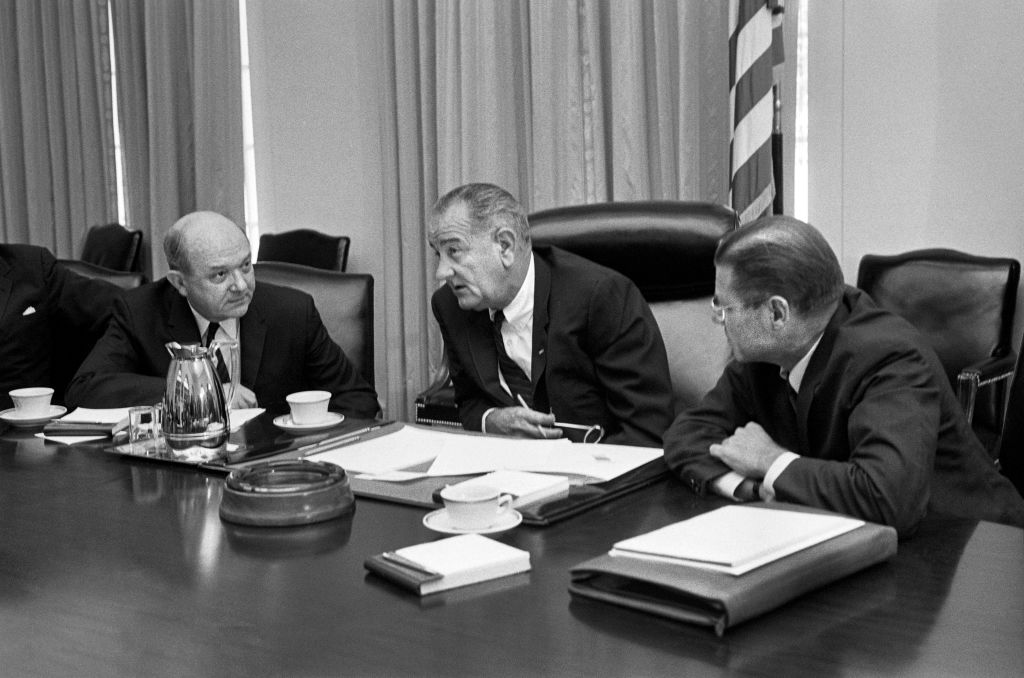

It was 1993 when a literary agent approached Random House with a proposal for a memoir by Robert S. McNamara, whose years as defense secretary for Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, 1961-1968, coincided with the U.S. buildup in what became the Vietnam debacle.

As a reporter, I had covered the war for The Washington Post and knew McNamara slightly. Now a senior editor at Random House and publisher of its Times Books imprint, I took on what we considered a major project, sure to be controversial.

McNamara was anathema to a great many in Washington’s political and journalism circles. Cynics said he had taken the presidency of the World Bank to atone for his actions as defense secretary. He was the target of particular contempt because he appeared to be so self-confident about the war’s progress as defined by data when he had, in fact recognized early on what the war’s trajectory would probably be.

Bob’s intention was to tell the full story of his life including his time at the Ford Motor Company, where he was the president as well as the World Bank. He planned a chapter or two on Vietnam. In our first meeting, I told Bob that his book would be read most closely for what he had to say about Vietnam and urged him to write that chapter first. He agreed. In a matter of months, he came back with 100,000 words on why the Kennedy and Johnson administrations had driven policy the way they had. He provided a strikingly non-judgmental portrayal of his views.

The team on the book included a young historian, Brian VanDeMark and Geoff Shandler, a young editor at Times Books. We had many sessions with Bob and transcribed the interviews. For all the progress we made, I felt we still hadn’t broken through to Bob’s private despair over the conflict and how it had divided the nation. In one of our last sessions, under careful prodding from Geoff and me—“How do you feel when you visit the Vietnam memorial on the mall with the names of every American killed in the war?”—Bob said, “We were wrong terribly wrong, and we owe it to future generations to explain why.” Geoff recalls that I was already gathering my papers to leave when McNamara said that, and I sputtered something akin to “That’s it!”

The release of the book in March 1995 was explosive. It became the leading news story in the country for days because of the level of outrage it provoked. Many people felt that McNamara’s silence about the war for a quarter century disqualified his right to explain it and to explain himself.

There were many reasons—largely inaccessible—why Bob had not openly discussed his views earlier, although those who knew him well in Washington were aware of his anguish over the war and saw that he would tear up in talking about it. He was not of a generation that was given to openly sharing feelings, preferring instead to have a few alcoholic “pops” to ward off emotion. National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, whose role in the war was comparable to McNamara’s escaped ignominy by maintaining what was regarded as a dignified silence and was hailed for his progressive leadership of the Ford Foundation.

If there were any people who saw the revelations in McNamara’s memoirs as an act of courage—literally no other major architect of the war ever admitted it was “terribly wrong”—they were drowned out by the attacks. Bob’s tendency toward rhetorical bluster meant that his public appearances were insufficiently contrite to satisfy his critics. Still, the book immediately went to number one on bestseller lists.

At an appearance at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government where the atrium was packed with reporters and television cameras on hand to gauge the response, near the end of the evening a Vietnam vet began to harangue Bob to what seemed the approval of much of the audience. McNamara snapped “Shut up.” My son, Evan, an undergraduate at Harvard, was sitting next to me and squeezed my knee hard, reflecting the tension he felt with me and the rest of the room.

Very early the next morning there was a knock on my door at the Charles Hotel and there was Bob in a raincoat and running shoes preparing to take a brisk walk along the Charles River. “I know what makes people so angry, “he said, “but I have to do this. I need to talk about the war and its lessons so we can prevent anything like it happening again.” Bob continued to travel, flying alone from city to city. Given the level of indignation the book had caused, we offered him security if he wanted it. He did not.

One of the moments that stand out to me as emblematic of the distance Bob had travelled, came when I introduced him to David Harris, a celebrated antiwar protestor of the 1960s, who had been president of the student body at Stanford, burned his draft card and gone to prison. Times Books had commissioned Harris to go to Vietnam and write a book exploring his impressions of the country and his own experiences. I recently asked David what he remembered of that encounter; he responded that Bob gave him an inscribed copy of In Retrospect writing, “To David Harris. With Admiration. Robert McNamara.” David said that he was stunned, and all these years later still was.

A few years later, Bob called and said a filmmaker named Erroll Morris wanted to make a film based on interviews with him. Knowing that Morris’s films were darkly revealing about his subjects, I asked Bob what his capacity for further excoriation and humiliation would be. Bob went ahead with the film The Fog of War, which was on the whole a fair portrait of an old man struggling to convey his thoughts about the past as far back as World War II, when he had been an army bombing officer who chose civilian targets in Japan. “We burned to death 100,000 civilians in Tokyo,” he said, noting that had the United States lost the war he might have been tried as a war criminal for that. The film was a critical success and was the 2004 winner of an Oscar for best feature documentary.

Robert McNamara would never be forgiven by the vast majority of Americans, but when he died in 2009 at the age of 93, he was at least better understood.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com