In the early 1990s, Welsh writer and television producer Russell T Davies heard the same story from many families about their experiences in earlier years: parents who arrived at AIDS wards at British hospitals to discover that their son was gay, that he had AIDS, and that he was dying, all in one moment. “That story haunted me,” Davies says. Over the three decades since, he’s wondered what happened and what was said in those moments, and wanted to do those stories justice.

Those anecdotes served as a starting point for the new British television series It’s a Sin, which follows the joys and the tragedies of a group of gay men and their friends living in London during the AIDS crisis of the 1980s. On Feb. 2, the day TIME speaks with Davies and the show’s lead actor Olly Alexander, they’ve just been told that the series has broken its channel’s viewing records. “We’re getting two reactions, which are people of my generation, remembering people they haven’t spoken about for a very long time, very often because the death was considered to be so secret and tragic,” says Davies, “and at the same time, you’ve got a younger generation who are watching this and they cannot believe what they’re seeing. They cannot believe that the gay or queer life in any shape or form was once treated so badly in a very recognizable world.”

The series, which airs on HBO Max on Feb. 18, may already be having real impact off-screen in Britain. The first week of February marked National HIV Testing week in the U.K., and sexual health charities estimate that the final number of tests taken will easily be three times the number of tests that were done in previous years—crediting the show as well as vocal efforts from its actors to promote testing. Many have also drawn parallelss between the way homophobia was rampant in the British press and society during the 1980s, and how transgender people have been treated in recent years. “Looking through some of the headlines in the U.K. in the 1980s, about the ‘gay plague’ and ‘gay cancer,’ and the way that gay people were reported on is so shocking to me,” says Alexander, who plays Ritchie, who moves from the Isle of Wight to London and becomes an actor in the series. “And when I look at headlines today, and the way trans people are reported on, it shocks me.”

Bringing history into the present

It’s a Sin starts in 1981, as five friends from different backgrounds and different parts of the U.K. find acceptance and love from one another in London. As the series progresses, the shadow of the AIDS crisis grows—misinformation around the then-mysterious illness is rife, and the sense of stigma and shame associated with it runs deep. By the end of 1984, there were 108 AIDS cases and 46 deaths in the U.K., and the following year, every region in the world had at least one reported case of AIDS, with more than 20,000 cases in total.

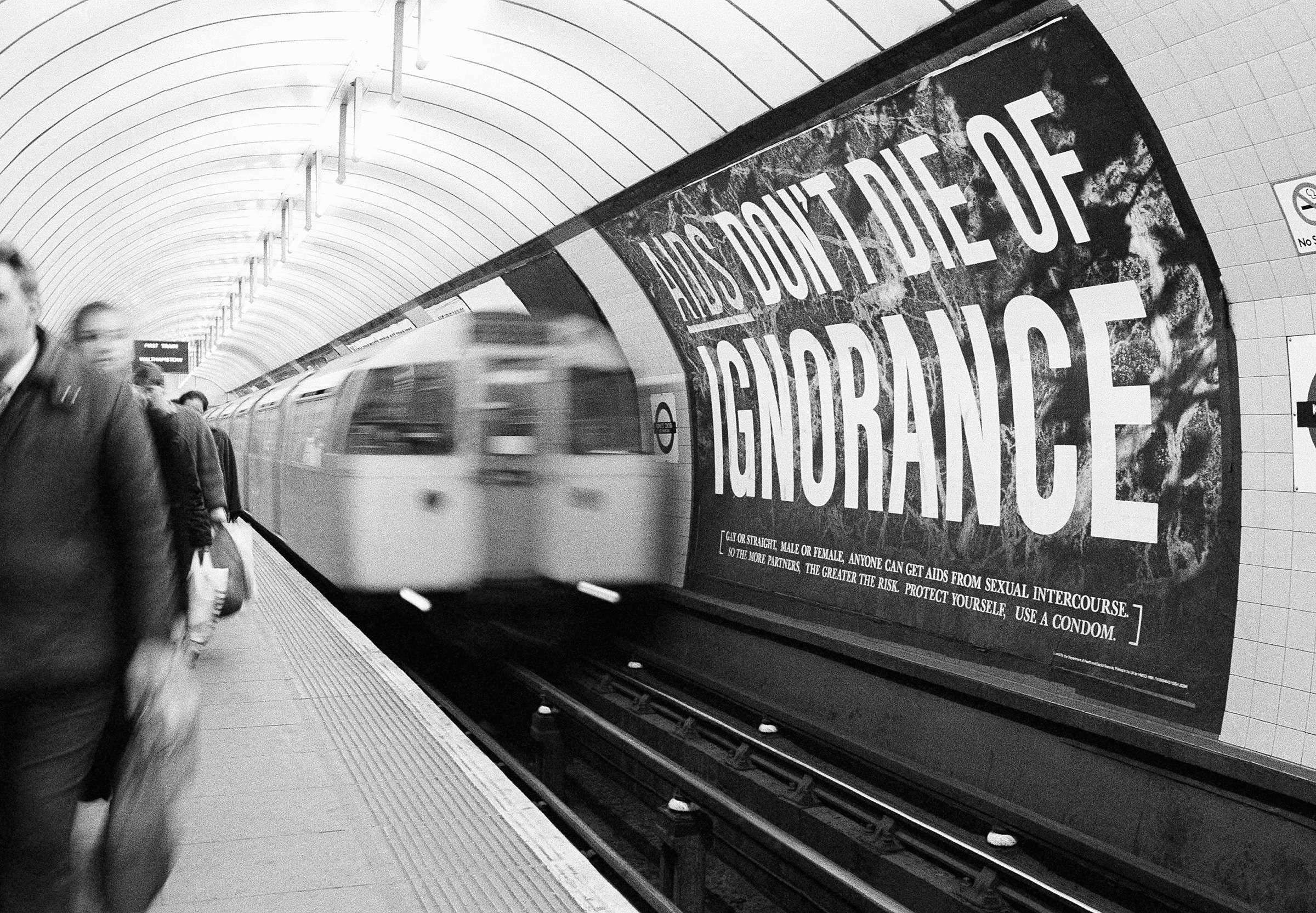

For LGBTQ rights campaigner Lisa Power, working on the series as a historical consultant brought back memories, some painful. She says that while many people think that the coronavirus pandemic is the first pandemic of their lifetimes, remembering and recognizing this history teaches us that that is not the case. “[AIDS] was ignored by a large chunk of the general public, except for when they saw tombstone adverts,” she says, referring to an ominous, 40-second long 1986 public health advert that featured ‘AIDS’ engraved on a black tombstone. “That’s the only recollection most people have of what was actually a horrific time for sections of the community in the 1980s.” And as creator Davies says, the parents of the men who died during that time are starting to pass away now, meaning the stories celebrating individual lives during this time risk being lost or remaining untold.

Read More: Pose Shines a Revolutionary Spotlight on Trans Lives

The show has also been heralded for sharing more of the British experience of the AIDS crisis, while showing the fullness and complexity of queer lives. Writer, performer and filmmaker Amrou Al-Kadhi says that it was refreshing to see joy depicted through friendships in the show, and poignant to see how much denialism there was around the epidemic due to misinformation and stigmatization of gay men. “It’s obviously had such a landmark effect in the U.K., because there hasn’t been really an AIDS representation in the U.K., so it did feel particularly new,” they say, pointing to cultural works that portray the U.S. experience of the AIDS crisis, like Angels in America and Pose. They hope more stories can be told about queer, intersectional experiences. “The success of It’s a Sin shows that if you write really good characters who you love, then audiences will come on whatever journey you take them on,” they say.

Decreasing stigma around HIV and AIDS

Several scenes of the series resonated powerfully with Ian Green, who was 18 in 1982, around the time when the series begins. He related to Ritchie’s character, who is shown constantly checking in the mirror to see if he has developed kaposi sarcoma—lesions found on the skin seen on people with an advanced HIV infection. “I used to do that all the time,” says Green, who is now CEO of the Terrence Higgins Trust, the U.K.’s leading HIV and sexual health charity, named after the man who was one of the earliest known people to die of an AIDS-related illness in the U.K. in 1982. “I had a stick with a mirror on the end to make sure I could see all the way down my back, to check that there were no lesions,” Green recalls.

When Green was diagnosed with HIV in 1996, he was told at the time that he would have eight to 10 years left to live. Due to treatment and medical advances, he has a normal life expectancy now, indicative of how much things have changed since the 1980s to the point where medication means that HIV can be a manageable, non-transmissible condition. But while the treatment may have changed, stigma remains, as persistent misinformation and false beliefs around HIV and AIDS are prevalent today. Although there is no risk of getting HIV through kissing, sharing utensils or other day-to-day contact, polling in 2019 showed that almost half of British people would feel uncomfortable kissing someone living with HIV, while 38% would feel uncomfortable going on a date with someone who is HIV positive. In the U.S., about half of people surveyed in a 2020 poll said they would be uncomfortable having a partner or spouse with HIV, and 59% said “it is important to be careful around people living with HIV to avoid catching it”.

While those attitudes won’t change overnight, there have been promising signs of progress in recent weeks that many, including Green, credit It’s a Sin for. “As a drama, It’s a Sin has facilitated a national conversation about HIV, which wasn’t there before,” he says.

Holding a mirror up

As in the U.S., broader British society and media were deeply homophobic during the AIDS crisis. Authority figures freely commented that those living with HIV/AIDS were “swirling in a human cesspit of their own making,” tabloid headlines whipped up fear and a moral panic around gay men, and the British government in 1988 passed Section 28, which forbid councils and schools from “promoting the teaching of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship.” The legislation was only repealed in 2003 and its harmful legacy is still felt today.

And while it’s certainly not the case that homophobia is no longer present in British media or society, many pointed out the parallels between the moral panic around gay men depicted in It’s a Sin, and the current wave of transphobia aimed at trans women in the U.K. today. Particularly since 2017, articles in the British press have consistently denied the lived experiences and realities of trans people, and influential journalists and public figures have falsely positioned trans rights as being in conflict with women’s rights. Alongside this toxic environment, transphobic hate crime reports have quadrupled over the past five years, trans people have been intentionally excluded from gender-based violence services and also face lengthy waiting times to receive the appropriate healthcare they need.

For those who lived through the smear campaigns against gay men in the 1980s, the same mischaracterizations are now being directed toward trans people, with similarly damaging consequences. “They’ve just changed the target, but they’re exactly the same arguments,” says activist and campaigner Christine Burns, editor of Trans Britain: Our Journey from the Shadows, who recalls how the negative tropes of the 1980s affected all members of the LGBT community to a certain extent. “I think a lot of people actually seem to be gaining messages out of It’s a Sin for this current time, in terms of being reminded that all the stuff they’re being asked to believe now was being said about another group 30 years ago.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com