One of the great actresses of the 1970s—and that’s if you’re drawing up a list of, say, three—didn’t have many big starring roles in film; she would end up landing some of her most prestigious parts in television and theater. But the career of Cicely Tyson can’t be assessed by the number of big film roles she had, especially given that in the ‘70s, Hollywood had no idea what to do with a Black woman possessed of gifts as magnificent as hers were. Tyson, who died on January 28, at age 96, leaves a legacy to be studied by generations going forward: working in an industry that could barely be bothered to make a place for her, she carved her own path out of rock, so that others might follow. Her performances will resonate forever, a ghost echo whose magnitude can’t be measured in Oscar nominations or other official accolades. And in her refusal to take roles that debased Black people, her greatness lies as much in the roles she refused to take as those that she did.

Tyson was born in East Harlem in 1924, the daughter of West Indian immigrants. After high school, she landed modeling jobs; she studied at the Actors Studio in the 1940s. (Her mother, a strict Christian who had raised Tyson and her siblings largely on her own, disapproved.) Early in her career, Tyson landed roles in television and onstage, often earning good notices. But it wasn’t until 1972, with her astonishing portrayal of Rebecca, a sharecropper, wife and mother in Martin Ritt’s Sounder, that the greater world got the chance to see her brilliance. Although the performance earned her an Academy Award nomination, great film roles didn’t automatically tumble her way. But Tyson worked hard, and she worked often: by the end of her life, she had appeared in 29 movies and more than twice as many television series or single episodes. Though most of the world knows her from her film and TV performances (she won three Emmys for the latter), she was also a formidable onstage presence: In 2013, at age 88, she became the oldest person to win a Tony, for her role in the revival of Horton Foote’s The Trip to Bountiful.

And Tyson, onscreen, onstage or off, was simply a magnificent presence. Her beauty was the generous kind, holding a mirror to other Black women of her generation, and all that would follow. Even without words, she urged them to see the same beauty in themselves. She helped bring the Dance Theater of Harlem into being. A school in East Orange, N.J., the Cicely Tyson School of Performing and Fine Arts, has been named after her. Just before her death, she published a memoir, Just As I Am. Tyson leaves behind not just a body of performances but a way of being, of living in the world, that it would do us all good to emulate.

To gaze upon her onscreen is one way to celebrate her: In the 1974 television movie The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, adapted from Earnest J. Gaines’s novel, she plays a woman who has reached the age of 110, a survivor of slavery who agrees to share her story with a young white journalist. For much of the performance, Tyson’s face is altered by age makeup, at the time less sophisticated than it is today. But those applied wrinkles can’t dim her resplendence. As Miss Pittman, Tyson shows us a robust spirit seeking to push the boundaries of a frail, aged body. Her gaze is soft, with flashes of flintiness; with her eyes alone, Tyson tells a story of hardship and fortitude that reaches a place beyond words. For all the ways in which our society remains twisted in its backwards vision, Tyson worked hard to push it forward.

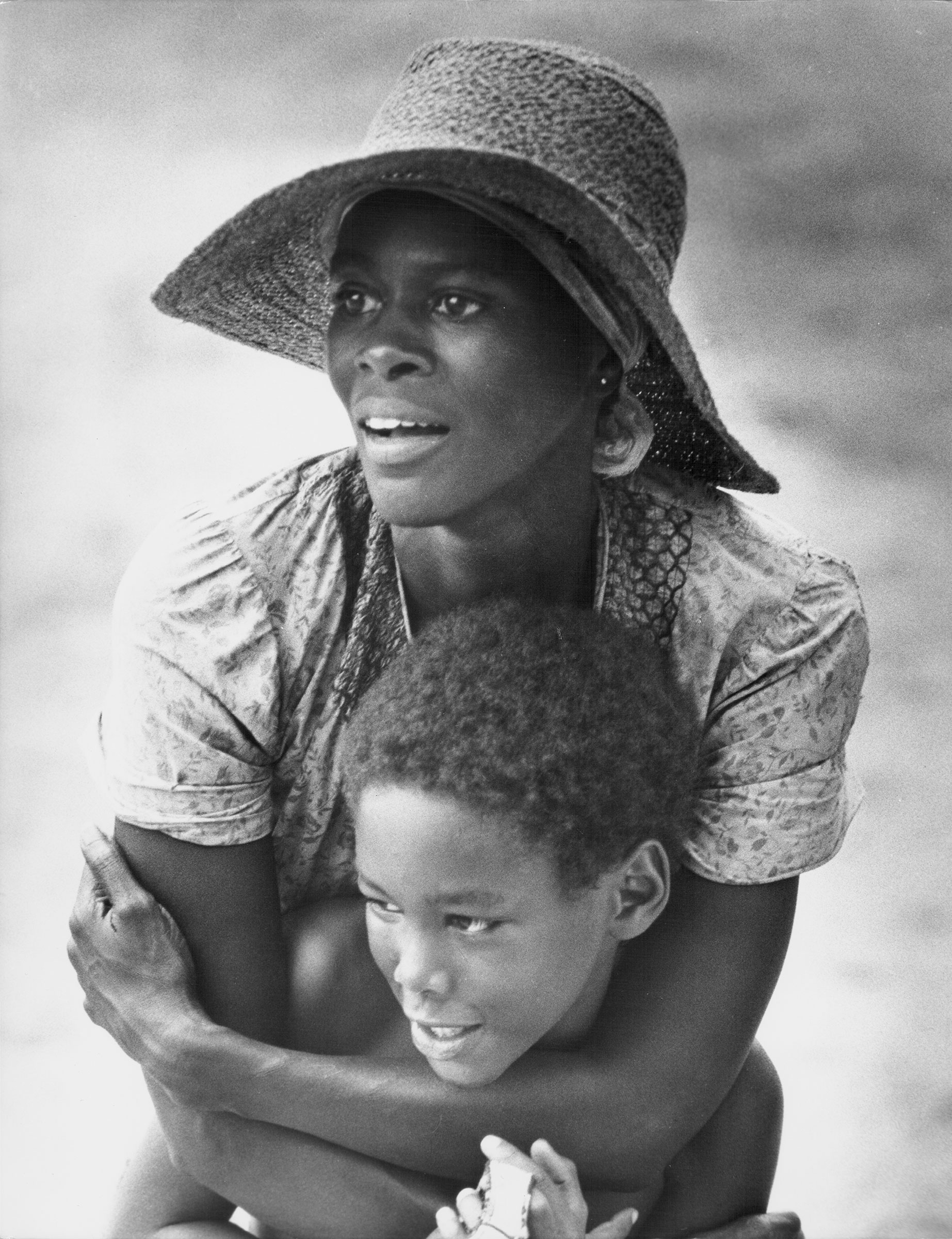

Acting isn’t always just storytelling; at its best, it pushes so deep into our hearts that we become a vessel for the story. That’s what Tyson does in Sounder, set in 1933 Louisiana and adapted from William H. Armstrong’s novel. (It’s also an example of the socially progressive filmmaking that some directors could push into being in the ’70s, even within the Hollywood mainstream.) Tyson’s Rebecca is left alone to care for her three children when her husband, Nathan (Paul Winfield), is arrested and imprisoned after stealing a chicken to feed his family. Rebecca’s life of worry shows on her face—with cheekbones that accept and reflect light as if it were a gift, she’s never anything less than beautiful, but her radiance glows through a veil of anxiety. When Rebecca has to face a white storekeeper—also her family’s landlord—after her husband’s arrest, he reminds her, his voice metallic with condescension, how much he’s done to help her family. She accepts his scolding politely, because she has to. But there’s a sea of feeling rolling beneath the very surface of her face, some waves glinting with resentment and anger, but most of them shimmering with a pride, a sense of self, that can’t be touched. And in a late scene, when she first glimpses Nathan from across a field, finally returning after serving his sentence, the cautious joy on her face—a rush of concurrent relief and disbelief—tells thousands of stories in one.

Tyson knew how to teach—without instructing or lecturing—by inviting us deep into another person’s world, another person’s history. If you saw Sounder as a kid, upon its release, what she showed you has likely stayed with you for a lifetime. If greatness is a quality that continues to unfold over generations, then Tyson’s is nowhere close to reaching its half-life.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com