Perhaps the Golden Age of Hollywood wasn’t so golden after all. At least that seems to be the idea behind award-winning director David Fincher’s new movie Mank, a black and white drama about Citizen Kane screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz which arrived on Netflix Dec. 4 with much awards fanfare.

Told in a series of flashbacks from the three months in 1940 that Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) spent at a secluded southern California ranch writing the first draft of what would become 1941’s Citizen Kane, the historical drama charts the screenwriter’s fall from Hollywood grace over the course of the 1930s. It culminates in Mankiewicz’s legendary battle with Orson Welles (Tom Burke) over screenplay credit for Citizen Kane—a controversy that continues to inspire debate to this day.

In Mank, Fincher (Gone Girl, The Social Network) portrays Mankiewicz as a brilliant, witty and observant writer who could never quite overcome his own demons—alcoholism and a gambling addiction among them. In a recent interview with Vanity Fair, Mankiewicz’s grandson Ben Mankiewicz said that the film’s representation of Mank aligns with his perception of his grandfather.

“It fully comports with my image of my grandfather, as relayed by mostly my father, but also my mother, the few years that she got to spend with him—that he was the smartest person in the room, the funniest person in the room…even when he had been drinking, which was often,” Mankiewicz said. “He was never mean. Ever. My father really admired him—even though, of course, he wished that he hadn’t self-destructed in the way that he did.”

But while Mank is certainly the film’s central figure, it’s the Old Hollywood elites surrounding him—including actor Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried), media mogul William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance) and MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard), who ground the story in the larger context of the Golden Age, and in particular the messy influence of politics and media moguls on Hollywood picture-making.

Below, read a who’s-who of the major characters in Mank.

Read TIME’s review of Mank here

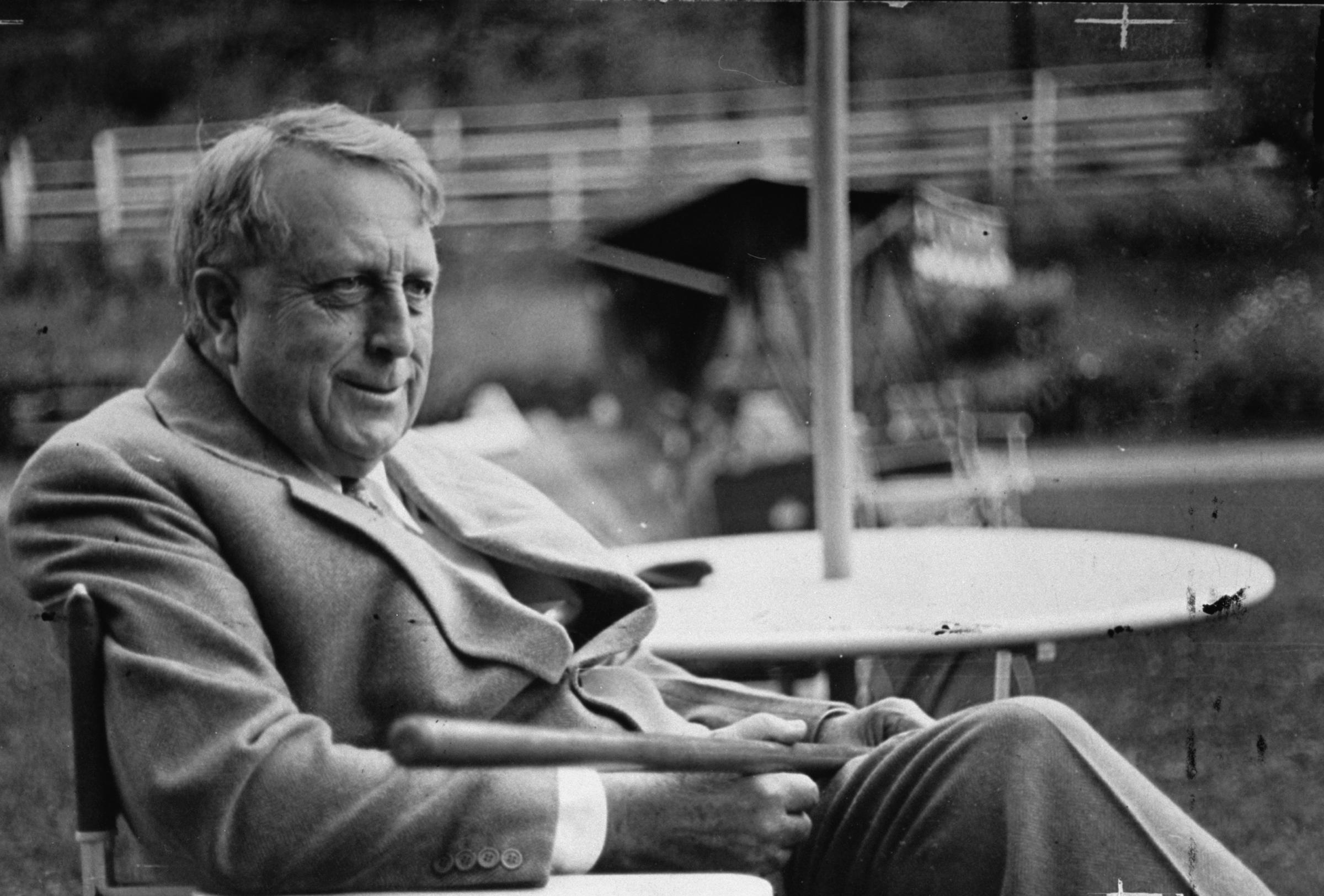

Herman Mankiewicz

From his struggles with alcohol to his friendship with Marion Davies, the broad strokes of Mankiewicz’s life as depicted in Mank are largely based in truth. Mankiewicz began his writing career as a journalist and sometimes playwright who served as the original theater critic for the New Yorker and a member of the Algonquin Round Table. After arriving in Hollywood in 1926, he found success working for studios like Paramount and MGM on movies such as Man of the World, Dinner at Eight and, later, The Wizard of Oz. He also recruited a number of his fellow East Coast writers to join him in Tinseltown, including his brother Joseph (played in Mank by Tom Pelphrey).

By the early 1930s, the timeframe of the earliest events in Mank, Mankiewicz had earned a reputation as one of the great personalities in the biz and begun rubbing shoulders with Hollywood power players like Mayer and Hearst. However, he was also known for his self-destructive tendencies and social outbursts, and by the summer of 1939, found himself unemployed. At around the same time, he broke his leg in a car accident. As depicted in the film, it was at that low point in Mankiewicz’s career that 24-year-old Hollywood newcomer Welles hired him to work on Citizen Kane.

While Fincher’s portrayal of Mankiewicz’s support for Socialist activist Upton Sinclair’s 1934 bid for California’s governorship is questionable (it’s believed that his politics leaned somewhat conservative), Mankiewicz did in fact help rescue German refugees ahead of World War II, as mentioned in the film—although he didn’t save an entire town.

In the biography Mank: The Wit, World and Life of Herman Mankiewicz, author Richard Meryman wrote, “Herman became the official sponsor for hundreds of German refugees and took responsibility for total strangers fleeing to America. [Producer] Sam Jaffe protested that he could not possibly fulfill these obligations. Herman continued to sign a stack of affidavits and said, ‘Yes, but the government doesn’t know that.’”

Orson Welles

Welles only appears in a handful of scenes throughout Mank, but his shadow hangs over Mankiewicz’s struggle to finish the script that he’s been hired to write— tentatively titled American—in a matter of months.

Just as MANK‘s opening title card states, “In 1940, at the tender age of 24, Orson Welles was lured to Hollywood by a struggling RKO Pictures with a contract befitting his formidable storytelling talents. He was given absolute creative autonomy, would suffer no oversight, and could make any movie, about any subject, with any collaborator he wished.”

After garnering nationwide fame from his 1938 radio broadcast of H. G. Wells’ classic science fiction novel The War of the Worlds, Welles was given carte blanche by RKO to make his first feature film. But, as Mank suggests, he was a Hollywood outsider and disliked by many in the industry. Enter Hollywood insider Mank.

Ultimately, Welles, Citizen Kane‘s director, star and co-writer, and Mankiewicz would share screenwriting credit for the film, but neither attended the 1942 Academy Awards, where they both won an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay.

Marion Davies

We first meet Davies in Mank when she’s screaming from atop a pyre constructed as part of a movie set on William Randolph Hearst’s—or as she calls him, Pops’—infamous San Simeon estate. “This is all Pops’ idea,” she tells Mank. “He wants me ready to take on the talkies.”

In real life, the Brooklyn-born Davies was the longtime live-in mistress of Hearst and a Golden Age starlet who starred in a total of 46 films (including 16 talkies) over the course of her career. Davies was renowned for the lavish events she hosted for Hollywood’s elite as well as her generosity to charities.

“The perception was that she was not that bright, a comedienne, a really very flighty young woman,” Amanda Seyfried, who plays Davies in Mank, told CBS News. “She was actually so much smarter than people gave her credit for.”

As depicted in Fincher’s film, Davies also had a close friendship with Mankiewicz. “What I knew from my dad was that my grandfather had a very close relationship with her,” Ben Mankiewicz told Vanity Fair. “Hearst kept the house dry, but there was a secret bar, as it was described to me—and Marion and Herman would sneak away during Hearst’s screenings and have a drink and talk.”

Read about Amanda Seyfried in TIME’s Best Movie Performances of 2020

William Randolph Hearst

The inspiration for the titular Charles Foster Kane in Citizen Kane, Hearst was a powerful media magnate best known for developing America’s largest chain of newspapers in the late 19th century—including a number of publications that dealt in sensational yellow journalism.

Despite running for office as a Democrat several times early in his career—winning two terms to the U.S. House of Representatives but losing bids for New York City mayor, New York governor and U.S. president—Hearst’s political leanings later shifted to the right. When the 1934 California gubernatorial race rolled around, Hearst threw all his support behind Republican incumbent Frank Merriam in order to defeat Democratic nominee Upton Sinclair (played in Mank by Bill Nye—yes, the Science Guy). However, it’s unclear if this is the event that prompted Mankiewicz, who was once friends with Hearst, to turn on him, as Mank suggests.

The portrait that Citizen Kane painted of Hearst and his Xanadu-like San Simeon castle was none too favorable, prompting Hearst to undertake a smear campaign against the film and Welles, its director.

Louis B. Mayer

As the head of MGM, Louis B. Mayer was an ultra-powerful figure in Hollywood at a time when the studio system reigned supreme. After co-founding MGM in 1924, Mayer propelled the studio to great success, earning it the nickname of the “Tiffany studio,” where there were “more stars than there are in the heavens.”

Despite personally earning the highest paycheck in America, Mayer really did ask his employees to take a 50% pay cut during the Great Depression, as we see in the film. He then broke his promise to pay them all back once the banks reopened.

As state chairman of the Republican party in California, he also called on his employees to make voluntary donations to Frank Merriam’s campaign and, alongside MGM executive Irving Thalberg (played in Mank by Ferdinand Kingsley), produced a series of fake newsreels in support of Merriam amid the 1934 California gubernatorial race.

Mayer was also reportedly a predatory figure. “Long before Weinstein there was Louis B. Mayer, who co-founded Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios in 1924,” Variety wrote in 2017. “Mayer, the ground zero of this kind of abuse, had means, motive, opportunity and that critical piece of the puzzle: the whip. If women didn’t comply, he’d threaten to ruin their careers or those of their loved ones.”

One example of the control Mayer and MGM exercised was in the career of Judy Garland; it was reported that the studio used amphetamines and barbiturates to control young actors like Garland on set and that Mayer groped and sexually harassed her for years.

Irving Thalberg

Nicknamed the “boy wonder of Hollywood,” Irving Thalberg served as MGM’s head of production from 1925 until his death at the age of 37 in 1936. Over the course of those years, he oversaw nearly every creative aspect of the estimated 400 films that he helped produce, becoming known for his unique vision and inherent flair for storytelling and transforming the movie business in the process.

As depicted in Mank, Thalberg worked closely alongside MGM studio head Mayer and produced fake election newsreels as part of a smear campaign against 1934 California gubernatorial candidate Upton Sinclair, prompting the New York Times to dub him the “Father of the Attack Ad” in 1992.

Thalberg’s premature death from pneumonia came as a great shock to many in Hollywood.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Megan McCluskey at megan.mccluskey@time.com