Among the thousands of books about Nazism, barely a handful focus on the wives of the leading figures in Hitler’s regime. While their men have left an indelible imprint on our collective memory the women who gave them vital support, encouragement and direction have largely remained relegated to the footnotes of history. Part of the reason for this is the nature of the source material, much of which has to be treated with caution. Although a lot more information has come to light in the last few decades, there are still considerable gaps and chunks of time missing from the diaries and letters that have survived, while the post-war autobiographies penned by several of the wives actively sought to portray their husbands as paragons of virtue and themselves as innocent bystanders.

However, the Nazis set out to control every aspect of their citizens’ existence—the food they ate, the clothes they wore, who they had sex with, what jokes they could tell, how they celebrated Christmas—making any separation between the public and the private meaningless. And even though they might not have been privy to their husbands’ daily decisions, the evidence of their murderous work was all around: the looted art on the walls; the furniture made from human skin and bones stashed in the attic; the fruit and vegetables taken from the local concentration camp gardens; the slave labor tilling their land. The rituals of family life—births, weddings, funerals—were inextricably linked to Nazi ideology. Perhaps this is why it has proved easier to take these women at face value and treat them as minor characters; treating them seriously means accepting that their husbands engaged in normal activities and experienced recognizably human emotions. Falling in and out of love. Worrying about the bills and their weight and where to send the kids to school. Planning dinner parties and picnics. Spending vacations sightseeing. Acknowledging that in many respects they were no different from the rest of us creates a form of cognitive dissonance: a deeply uneasy feeling.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Yet their story offers important insights into the nature of Nazi rule and the psychology of its leaders, providing a fresh perspective on the key events that shaped its rise and fall.

Gerda Bormann, wife of Martin Bormann, Hitler’s private secretary, was in many ways the ideal Nazi wife. She didn’t use cosmetics, had her blonde hair in a plait and wore traditional Bavarian dress, as did her children; in the few images of them that survived they look like they’ve just stepped off the set of The Sound of Music. At home, Gerda submitted without question to her husband’s demands. She had no public profile and no place in the regime’s publicity campaigns; at the party events she was obliged to attend, she remained hidden in the background. Most of all, she was a prodigious mother, producing children at a heroic rate: between 1933 and 1940, Gerda added five more to the two she already had.

As far as the Nazis were concerned, this was a woman’s essential function: to drive population growth. Increasing the birth rate was an overriding goal and the regime mobilized its forces to achieve this aim: there were economic incentives and cash handouts for large families; the propaganda machine made films, broadcast radio shows and staged exhibitions that glorified motherhood; the medical profession and the scientific community—especially nutritionists and fertility experts—got in on the act; and the Gestapo policed those considered unfit to be mothers. Overall, though the birth rate increased under those efforts—in 1933 there were just under 15 live births per 1,000 people, which had risen to 20 by 1939—it was still slightly less than it was in 1925, while the number of families with more than four children had dropped from a quarter in 1933 to a fifth in 1939. Gerda, of course, was the exception to the rule.

Martin Bormann worked tremendously hard, existed on only a few hours of sleep a night, and pushed his subordinates to the limit. His employees lived in fear of his quick-fire temper. Hitler knew Bormann was a terrible bully, but he got things done: “I can rely on him absolutely and unconditionally to carry out my orders immediately and irrespective of whatever obstructions may be in his way.” By all accounts, Bormann behaved the same way at home, which gave rise to the widely held view that Gerda was an oppressed, brow-beaten housewife. A prominent Nazi characterized Bormann as “the kind of man who takes delight in humiliating his wife in front of friends as if she was some lower form of being.” If domestic standards slipped a fraction, or something was done incorrectly or landed in the wrong place, Bormann would lash out at Gerda. Hitler’s valet said that everybody knew that Bormann terrorized his family: “In moments of uncontrolled rage he would resort to physical violence against his wife and children.” Bormann allegedly beat two of his children with a whip because they were frightened by a large dog, and kicked one for falling in a puddle.

It’s hard to assess how Gerda felt about such degrading treatment. She’d didn’t fight back. She didn’t seek help. She didn’t confide in anybody. Based on her Nazi ideology, Gerda believed it was her duty to obey her husband, and there’s every indication that she was truly devoted to Bormann. As far as her children were concerned, Gerda happily played with them, sang songs, drew pictures and read stories: it was their father’s job to discipline and punish them.

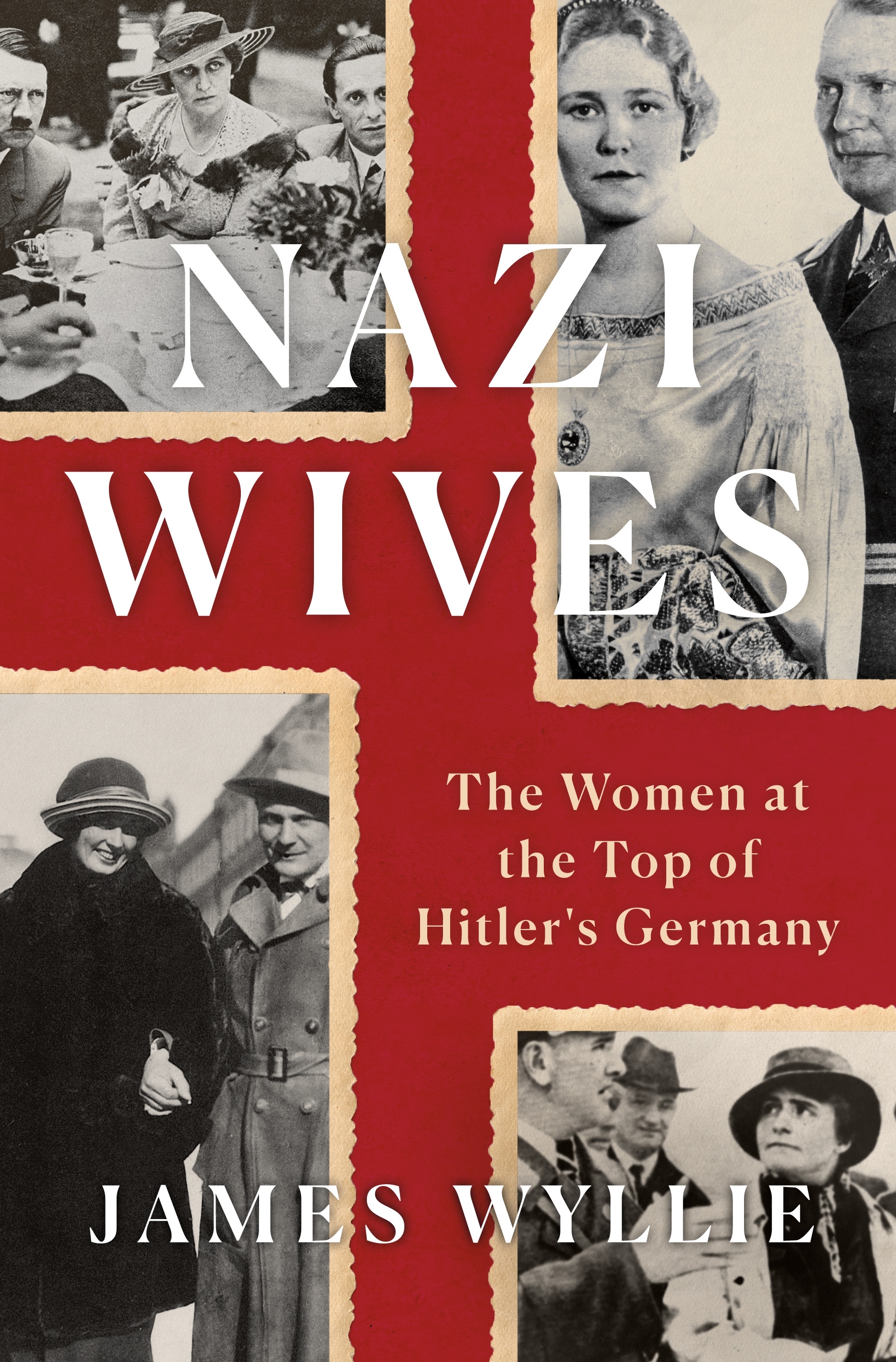

Excerpted from NAZI WIVES: The Women at the Top of Hitler’s Germany by James Wyllie. Copyright © 2019 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com