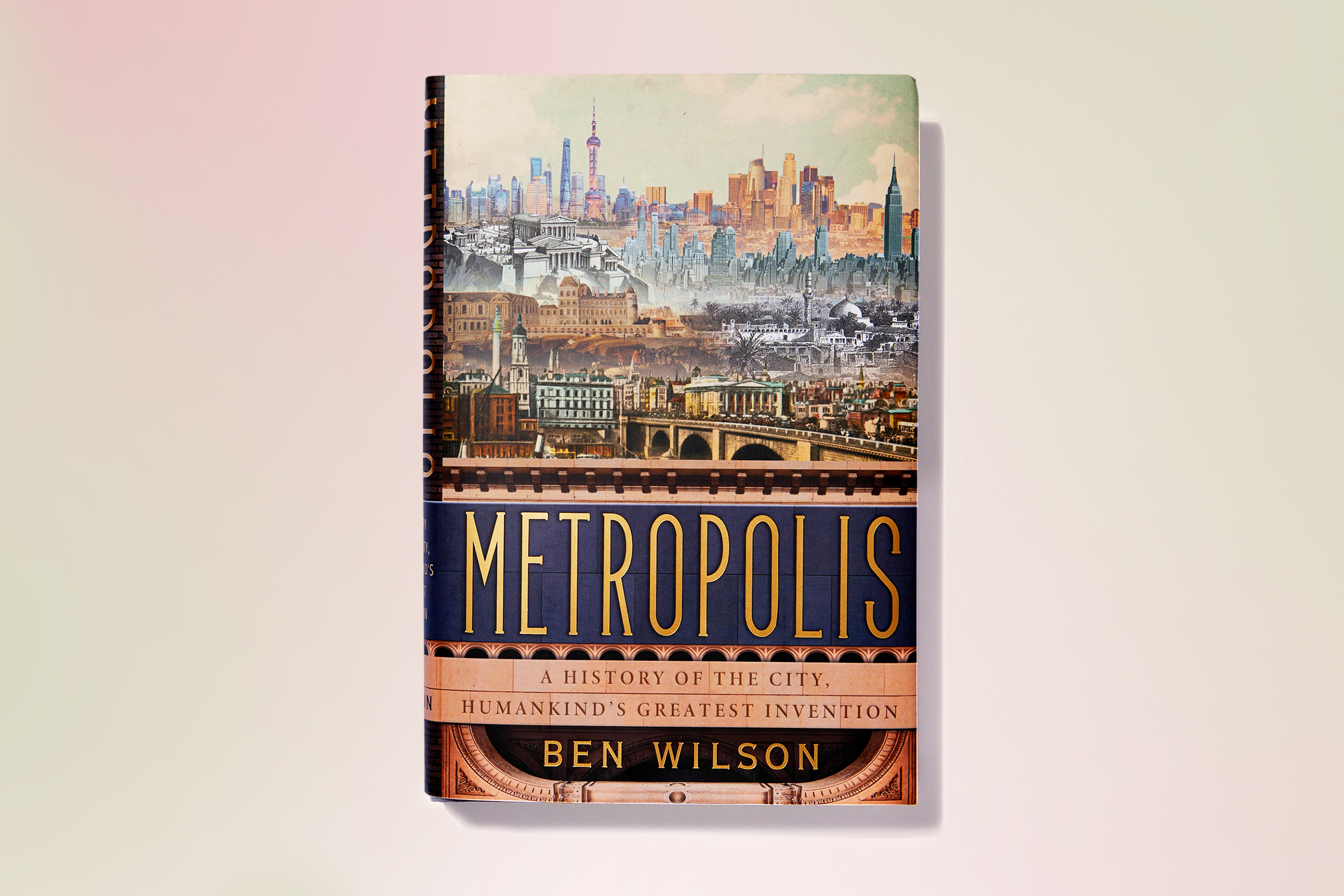

Rents are the most explicit metric of the premium people are willing to pay to enjoy the heady pleasure of living in the world’s great cities–and currently they are down sharply in New York and San Francisco. London and Paris recently imposed new rounds of lockdowns. So perhaps it’s not the ideal moment to publish Metropolis, an ode to cities and cosmopolitan life as “humankind’s greatest invention,” according to its subtitle. In a hastily added few paragraphs in the introduction, the author, British historian Ben Wilson, acknowledges that the COVID-19 pandemic “could turn the tide against cities once again encouraging people to flee metropolises.” But he also adds that “cities are resilient, adaptable entities capable of standing up to all kinds of disasters.” In fact, considering that many urban innovations are responses to disasters, perhaps it’s just the right moment for such a book.

Innumerable historical examples show that counting cities out is a sucker’s game. For one, Venice and other European centers lost at least 30% of their population to the plague in the Middle Ages. Beyond the enduring seduction and economic and environmental benefits of cities, Metropolis has the added virtue of Wilson as an erudite, creative guide to the history of civilization through its great urban areas. He is a voracious, eclectic reader and an artful deployer of quotations, from Plato to N.W.A. The Epic of Gilgamesh is read through an urban-planning prism. The opening credits of The Sopranos “is what urban geographers call a transect, a slice taken from the city centre to periphery that reveals a range of social and physical habitats,” Wilson writes.

He has a reporter’s eye for freshness, highlighting relatively recent archaeological discoveries of the grand cities of the Harappan civilization, circa 2600 B.C., in the Indus Valley. These cities were so clean that Wilson speculates they may have been the historical basis for the Garden of Eden story. “Few things symbolise collective civic endeavour more than the seriousness with which a city deals with its daily tonnage of human waste,” he writes. In the Indus cities, flush toilets were standard in the third millennium B.C., more prevalent than they are today in that region of Pakistan. His reporting takes readers to remote corners of China, where 700 mountains were literally moved, “razed … and the rubble tipped into valleys to create an artificial plateau on which a shimmering new skyscraper city” is being built. He broadens the book’s focus beyond the usual Western suspects, noting that all but one of the world’s 20 largest cities in the Middle Ages “were Muslim or in the Chinese Empire.”

Wilson is a sensualist, chronicling the sexual and gastronomical draw of densely packed people. He loves descriptive lists, citing author and co-founder of the satirical magazine Punch Henry Mayhew’s account of the most popular street foods of the 1850s: “fried fish, hot eels, pickled whelks, sheep’s trotters, ham sandwiches, pea soup, hot green peas, penny pies, plum duff,” and on and on. He provides an excellent account of the erotic draw of cities from ancient Babylon to the present day. He is also enamored of the energy and entrepreneurship of street life in emerging megacities such as Lagos. That city’s “messiness,” he writes, is not “a sign of poverty and shame,” but a dynamic sign of a developing city.

At this current scary moment, when crowded cities can seem dangerous, even life-threatening, looking at history to see what emerges from the other side is instructive in imagining what can come next. After the Black Death, rents fell and wages rose. Pre-pandemic, the world’s great cities were increasingly derided as playgrounds for the rich. It’s heartening to reimagine a New York, a London, a Hong Kong, where teachers, artists, mechanics, inventors and police officers could live, jointly creating the next triumphant iteration of civilization’s greatest invention.

This appears in the November 16, 2020 issue of TIME.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com